Top 10 list of the most disappointing final seasons in MLB history containing many of the game’s all-time great players.

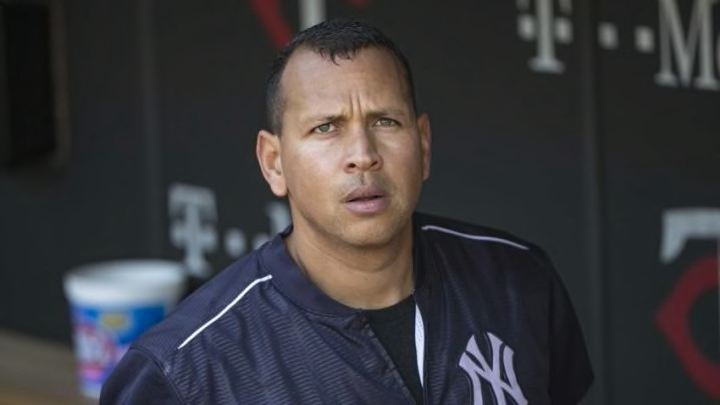

The 2016 season may be remembered for some of the most disappointing final seasons in MLB history for some once-great ballplayers. Mark Teixeira is straddling a .200 batting average and has announced he will retire at the end of the year. Alex Rodriguez was given one final week to mostly languish on the bench before he was released from his player’s contract with the New York Yankees even as he’s four home runs short of 700.

Prince Fielder’s body won’t allow him to continue to play, despite being just 32 years old, which is still relatively young in the “real world” but already in the decline phase of a baseball player’s career. Fielder’s very emotional press conference was heartbreaking to watch.

All three of these players are having disappointing seasons. This is not uncommon in baseball, but sad for the player and fans just the same. We would all love to see players go out like David Ortiz, currently having one of the best seasons of his career. Sandy Koufax went out at the very top of his game. His final season was 1966, when he was 30 years old. He won the Cy Young Award for the third time in four years, led the league in wins, starts, complete games, shutouts, ERA, innings pitched, and strikeouts. He was 27-9 with a 1.73 ERA. The he hung up his spikes because the pain in his arm was too unbearable to continue to pitch.

Ty Cobb hit .323/.389/.431 as a 41-year-old in his final season. Barry Bonds hit .276/.480/.565 in his final year. Even at 42 years old, Bonds led the league in on-base percentage and intentional walks. Of course, the poster child for great final seasons is Ted Williams, who hit .316/.451/.645 as a 41-year-old for the Red Sox in 1960. Williams’ home run in his final at-bat inspired John Updike to write “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu” for The New Yorker, with the famous lines regarding Williams’ career-long refusal to tip his cap to the fans—“The papers said that the other players, and even the umpires on the field, begged him to come out and acknowledge us in some way, but he never had and did not now. Gods do not answer letters.”

Very few players go out the way Ted Williams went out. Most players finish their career as a shell of their former selves. The better the player was, the more disappointing his final season can be.

Expectation always plays a role in disappointment. Joe Posnanski has a plus-minus system for rating movies he’s seen. If you go into a movie expecting it to be a 1 and it is a 1, you’ve received what you expected. If you go in expecting a movie to be a 5 and it’s a 2, that’s a -3. That makes it much more disappointing than the one movie even though it is objectively a better movie (2 is better than 1). Expectations matter. Someone like Willie Bloomquist (.159/.194/.174 in his final year) won’t qualify for any most disappointing final season’s list because expectations for a 37-year-old Willie Bloomquist were low to begin with. With this in mind, I rank the 10 players with the most disappointing final seasons in MLB history.

Next: An O's Hitter