MLB History: Top 25 third basemen in MLB history

Continuing our series on MLB History, today we look at the top 25 third basemen in the history of baseball.

We looked at the top 15 right-handed pitchers, the top 10 catchers, the top 25 first basemen, and the top 25 shortstops in baseball history. Now it’s time to look at the top 25 third basemen. For the most part, third base is a position where players can carry the lumber. Unlike shortstop, you won’t find any below average hitters here.

That’s not to say all third basemen are top tier hitters. One guy in particular on this list was slightly above average at the plate but a magician in the field. If you’re old enough, you may remember him making some incredible plays in the 1970 World Series. Even if you’re not that old, you’ve probably heard how good he was with the glove.

In Little League, the third baseman is one of the toughest players on the field. The mantra “knock it down and throw ‘em out” applies to the hot corner, where right-handed pull hitters send bullets down the third base line. Third baseman don’t need to range too far, but they need quick feet and a strong arm.

Historically, third base has been underrepresented in the Hall of Fame. On this list, there’s a top-10 third baseman who was on the Hall of Fame ballot for the first time last year and received just 10.2 percent of the vote. There are a few top-20 guys who didn’t come close to induction.

There are a couple active players who may surprise you, guys you might not think of as one of the 25 best third basemen of all-time. There are also some players who aren’t on the list that you think should be. In the case of Miguel Cabrera, it’s not that he doesn’t belong, it’s that he was predominantly a first baseman in his career. Otherwise, he would be. Dick Allen, Tony Perez and Harmon Killebrew are in the same boat.

Two versions of Wins Above Replacement (WAR) were used, those from Fangraphs and Baseball-Reference, along with Wins Above Average (WAA). Wins Above Average gives a little more credit to very good seasons. Jay Jaffe’s JAWS list was also part of the discussion.

In the end, 25 men made the cut and their careers span more than a century of baseball. Let’s look at the 25 greatest third basemen in the history of the game.

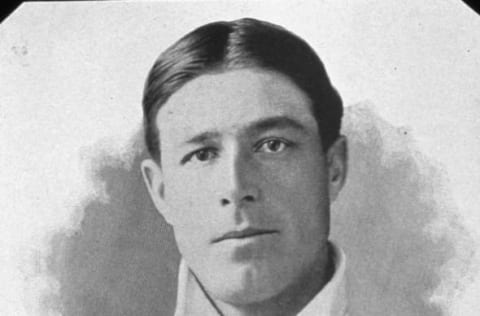

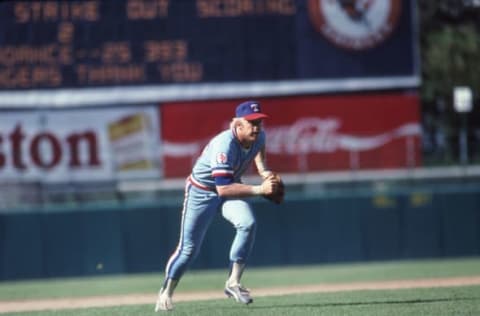

MLB History Toby Harrah (#25)

“Baseball statistics are like a girl in a bikini. They show a lot, but not everything.”—Toby Harrah

Toby Harrah played his rookie season with the Washington Senators in 1971. The next year, the franchise moved to Texas and became the Rangers. He had his first above average season with the bat in 1974 when he hit .260/.319/.417 and launched 21 homers. This was the first year in a nine-year stretch during which he hit .272/.375/.424 and averaged 81 runs scored, 17 home runs, 72 RBI, and 19 steals per season. He averaged 4.5 WAR per season during this stretch and made the all-star team three more times.

In one of those weird baseball oddities, Harrah played shortstop for both games of a doubleheader in 1976 and didn’t record a single chance. His double-play partner, second baseman Lenny Randle, had 11 assists in the two games. Harrah made up for his lack of activity in the field by getting six hits in the double dip.

Harrah made history again in 1977. In a game against the Yankees on August 27, Harrah hit an inside-the-park home run off Ken Clay in the top of the seventh inning. The very next batter, Bump Wills, followed with an inside-the-park home run of his own, making this the first time batters went back-to-back with inside-the-park home runs.

After 11 years in Texas, Harrah was traded to Cleveland in December of 1978 for Buddy Bell. He spent five years in Cleveland and continued to put up valuable seasons, averaging 3.7 WAR per year. His best year with the team was 1982, when he played all 162 games and hit .304/.398/.490 with 100 runs scored, 25 homers, and 78 RBI.

Another trade landed Harrah with the New York Yankees for the 1984 season, but that was a bust. He was traded back to the Rangers and finished out his career with two final seasons in Texas. In one last baseball oddity, Harrah was the last active player who played for the Washington Senators

In retirement, Harrah was named one of the 100 greatest Cleveland Indians players as part of the team’s 100th anniversary celebration in 2001. He was also inducted into the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame along with Ruben Sierra in 2009.

MLB History Bob Elliott (#24)

“Bob Elliott made the Braves. He’s the old-time type who hits and plays his best in the clutch.”—Rogers Hornsby, about Bob Elliott

Bob Elliott came up to the major leagues as an outfielder with the Pittsburgh Pirates. At the time, the Pirates home ballpark, Forbes Field, was tough on right-handed pull hitters. Elliott played eight years in Pittsburgh and never hit more than 10 home runs in a season.

After his third year with the Pirates, he was shifted to third base. His manager at the time, Frankie Frisch, thought his strong arm would be an asset at the hot corner and felt he would be a good replacement for the team’s regular third baseman, Lee Handley, who had left to serve in World War II.

While many players missed time for military service during World War II, Elliott remained home because of a head injury he’d suffered after getting hit in the head by a ball in 1943. He made the NL All-Star team three times in five years from 1941 to 1945. He also received MVP votes four straight years from 1942 to 1945.

After the 1946 season, Elliott was traded to the Boston Braves and his power hitting greatly improved with the change in his home park. Braves Field was a much better park for right-handed hitters. After hitting just five home runs in 558 plate appearances in 1946, Elliott launched 22 home runs in 645 plate appearances in 1947. He made the all-star team for the fourth time and was named NL MVP.

In 1948, Elliott had another all-star season. He hit 23 home runs, had 100 RBI, and led the league with 131 walks. The Braves made it to the World Series for the first time since 1914. They lost in six games to Cleveland, but Elliott hit .333/.391/.619 and had 2 homers and 5 RBI in the series.

Elliott played three more seasons with the Boston Braves, then played for three different teams in his final two seasons in the big leagues. He retired as the career leader in slugging percentage among NL third baseman. His 124 wRC+ is 17th among third baseman with 5000 or more career plate appearances.

MLB History David Wright (#23)

“I take great pride in going out there and playing through pain.”—David Wright

With the way his career has gone the last couple seasons, it might be easy for people to forget just how good David Wright was when he was young and healthy. Injuries have kept him off the field since May of 2016 and it’s taken a considerable amount of time for him just to be able to play catch. He did play catch at the end of May, but it’s unknown when he’ll get back on the field for actual games

The New York Mets drafted Wright with a supplemental pick (38th overall) in the 2001 June Draft. Along with Joe Mauer and Mark Teixeira, he’s one of three players with 50 or more career WAR from the first round of that draft

Wright moved through the minor leagues over the next few seasons and joined the Mets mid-season in 2004. He was very good right from the start, hitting .293/.332/.525 in 69 games. He continued to be very good for the next six years. From 2005 to 2010, Wright averaged 156 games played, 100 runs, 26 homers, 104 RBI, 22 steals, and a .306/.387/.515 batting line.

This was peak David Wright. He was not only good, he was also durable, playing 157 or more games five times in six years. He made the NL All-Star team five times and helped the Mets get to the NLCS in 2006. He was the face of the franchise and looked to have a long, great career ahead of him.

Trouble started brewing in 2011 when Wright was diagnosed with a stress fracture in his lower back. He only played 102 games that year. Then, to the relief of Mets fans, he bounced back with a 156-game season in 2012 and made the all-star team again. Maybe the stress fracture was just a blip?

It wasn’t. In 2013, hamstring problems limited Wright to 112 games, but he still hit .307/.390/.514. He wasn’t able to play as much as he had before, but he was still vintage David Wright when he was able to play.

In 2014, his shoulder hindered him. He gutted it out for 134 games, but hit just eight home runs and had a career-worst .269/.324/.374 batting line. Just as the Mets were improving, from fourth in their division in 2012 to third in 2013 to second in 2014, David Wright was struggling to be part of the ascension up the standings.

When the Mets made it to the World Series in 2015, Wright’s injuries prevented him from being much of a factor. He only played 38 games. He still hit .289/.379/.434, which wasn’t bad at all, but he just couldn’t get on the field often enough.

The Mets made the wild card game in 2016, but Wright ‘s season ended in late May after he appeared in 37 games and hit .226/.350/.438. Who knows if we’ll see him on the field again? He was good enough early in his career to make this top-25 list, but he had the potential to be so much higher.

MLB History Evan Longoria (#22)

“The opportunity to play at Long Beach was huge for me, going to a big school, getting that exposure, playing on that stage. A lot of physical maturity, along with the coaching I got at Long Beach, is probably the reason I’m standing where I am today.”—Evan Longoria

It may surprise many people to see Evan Longoria on this top-25 list of the greatest third baseman in MLB history, but Longo is nearly a 50 WAR player. He’s been 22 percent above average on offense after league and ballpark effects are taken into account (122 wRC+), whish puts him in the company of Scott Rolen, Paul Molitor and Bill Madlock. Longoria has been good with the glove also

The 2006 MLB draft had three first round picks who have been very good in their careers—Clayton Kershaw, Max Scherzer and Evan Longoria. Longoria was the third player taken, after Luke Hochevar (Kansas City) and Greg Reynolds (Colorado). Within two years he would be in the major leagues with the Tampa Bay Rays.

Longoria was among the best players on the Rays in his rookie year, despite only playing 122 games. He hit 27 homers and drove in 85 runs, with a .272/.343/.531 batting line. He made the AL All-Star team and won the AL Rookie of the Year Award.

The Rays, previously known as the Devil Rays, improved from 66-96 to 97-65, and won the AL East. It was their first winning season after finishing in last place in nine of their first 10 years. They made it all the way to the World Series, but lost to the Phillies in five games.

Longoria continued to be one of the Ray’s top players over the next few years. He made the all-star team twice more and had two Gold Glove seasons. An injury-marred 2012 season was a blip on the radar before he came back with another strong season in 2013.

In his first six years, from 2008 to 2013, Longoria averaged 5.7 WAR per season (Fangraphs). Only Miguel Cabrera was more valuable during those six years. His seasonal averages looked like this: 133 G, 570 PA, 78 R, 27 HR, 91 RBI, 6 SB, .275/.357/.512. The Rays were successful also, making the playoffs three more times. In 2011, Longoria hit a walk-off home run that sent the Rays to the wild card game.

The Rays and Longoria haven’t been as successful since. Longoria played four more years in Tampa Bay before being traded to the Giants last offseason. The Rays didn’t sniff a playoff spot in any of those years. Longoria dropped from a 5-to-6 WAR player to a 3-to-4 WAR player.

At 32 years old, Longoria is currently having the worst year of his career. He’s hitting just .246/.278/.434 (93 wRC+) and his usually above-average defense didn’t make the trip across the country. With five more years on his contract, the San Francisco Giants are hoping he rebounds from a bad start to the year. Unfortunately, he just suffered a hand fracture on a hit by pitch in a recent game.

MLB History Stan Hack (#21)

“Stan Hack has as many friends in baseball as Leo Durocher has enemies.”—Gabby Hartnett

Stan Hack has a background story from a time long before there were so many organized leagues or travel ball. After graduating from high school, he played baseball on the weekends. This wasn’t professional baseball; it was a semipro team. During the week he worked at a bank.

The Sacramento Senators, a local team in the Pacific Coast League, noticed Hack and signed him to a contract. He crushed it in the PCL, hitting .352 in 164 games. Bill Veeck, Sr., the president of the Chicago Cubs, bought Hack’s contract from the Senators and Stan Hack joined the Cubs, the only major league team he would ever play for.

Hack had the worst season of his career as a rookie in 1932, hitting .236/.306/.365 in 72 games. His struggles led to a demotion to Double-A, where he played most of the 1933 season with the Albany Senators. He didn’t hit much there either, but the Cubs still brought him up in late August and he was very good in a 20-game sample.

In 1934, at the age of 24, Stan Hack began to show off the skills he would become known for. One of these was his ability to get on base. He walked over 1000 times and had a .394 OBP in his career. He didn’t hit for much power, but hit for a good average, walked, and scored runs.

Because of his optimistic attitude and good looks, Hack took on the nickname “Smiling Stan.” Bill Veeck, Jr. was a young man working in the Cubs’ front office at the time. He arranged a ballpark promotion to take advantage of Hack’s popularity with the fans. The team handed out mirrors with Hack’s picture on the back. When fans tried to use the mirrors to reflect the sun into the eyes of opposing players, umpires threatened to forfeit the game.

In 1938, Hack led the league in games played, plate appearances and stolen bases. He made his first of five all-star teams and finished seventh in NL MVP voting. He would lead the league in plate appearances and stolen bases again the next season. He also led the league in hits twice.

The Cubs were a good ballclub in the 1930s and into the 1940s. They made it to the World Series four times in 14 years from 1932 to 1945. They lost all three, but Hack hit an impressive .348/.408/.449 in 18 World Series games.

Hack didn’t get much support for the Hall of Fame, but he gets much more credit from the more analytically minded baseball fans and analyists. Bill James was a strong proponent of Hack, rating him as the ninth-best third baseman of all-time in his Historical Baseball Abstract (2001).

MLB History Jimmy Collins (#20)

“Bunt ‘em down to me and I’ll show you something.”—Jimmy Collins

Jimmy Collins grew up with in Buffalo, New York, with his Irish immigrant parents and three siblings. He began playing baseball as a teenager for amateur teams in the area. While working for the railroad in 1893, he was offered a spot on a professional team in the Eastern League called the Buffalo Bisons. After two seasons there, he moved on to the Boston Beaneaters of the National League.

Collins spent five years with the Boston Beaneaters and averaged 4.3 WAR per season. His first great year was 1897, when he hit .346/.400/.482. He followed that up with an even better year in 1898, when he led the NL in home runs. He was also considered the best fielding third baseman at the time, with good range and a strong throwing arm.

Throughout his time with the Beaneaters, Collins battled management over his salary. He regularly made demands for more pay, but players in those days had no leverage and he usually had to settle for less than he felt he was worth. There was also a strong anti-Irish sentiment in Boston at the time.

Before the 1901 season, Collins jumped to the American League. He didn’t change cities, though, he just moved from the Boston Beaneaters in the NL to the Boston Americans in the AL. He negotiated a much bigger salary and took on the role of player/manager. A group of fans called the Royal Rooters followed him to his new team.

Collins continued to play well on the field and the Boston Americans finished second in 1901 and first in 1902. At the same time, Irish Americans were seizing political power in the city. John Fitzgerald, the maternal grandfather of future president John F. Kennedy, would become mayor of Boston in 1905.

The Americans won the league again in 1903. At the end of the season, the owners of the AL champion Boston Americans and NL champion Pittsburgh Pirates arranged for a series of games that would become a precursor to the World Series. The Americans won the best-of-nine series and the AL gained legitimacy in the eyes of the public. Collins, as player/manager of the winning team, earned national acclaim.

He used his newfound status to negotiate a lucrative deal with his team that included a profit-sharing arrangement. The Americans won the AL again in 1904, but the winner of the NL, the New York Giants, refused to play them in the postseason.

That was the high point of Collins’ time with the Boston Americans. His play on the field started to decline as he aged into his mid-30s and his ambition off the field led to problems with management. When the Americans had a 20-game losing streak in 1906, his hero status took a big hit. He started the 1907 season in Boston but would move to the Philadelphia Athletics for the rest of that season and one more.

After retirement from the big leagues, Collins became a real estate mogul in Buffalo. He spent 22 terms as president of the Buffalo Municipal Baseball Association. He was on the BBWAA Hall of Fame ballot six times from 1936 to 1945, but never received more than 49 percent of the vote. In 1945, the Old-Timers Committee inducted him unanimously. He was the first third baseman to make the Hall of Fame.

MLB History Ron Cey (#19)

“I was eternally grateful that I was able to live my childhood dream.”—Ron Cey

A native of Tacoma, Washington, Ron Cey played college baseball at Washington State University for legendary coach Bobo Brayton, who was head coach of the Cougars for 33 years. Cey played one year on the freshman team and a second year on the varsity before being selected by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 19th round of the 1968 draft. He’s the only player selected in that round that year to make the big leagues.

Cey spent three years in the minor leagues before getting into two games with the Dodgers in 1971. He spent most of the 1972 season in Triple-A before finally establishing himself as the Dodgers’ starting third baseman in 1973. On June 13, 1973, he played third base with Bill Russell at shortstop, Davey Lopes at second and Steve Garvey at first.

This foursome would be regulars in the Dodgers infield for the next eight-and-a-half years. Throughout the 1970s, it was Garvey, Lopes, Russell and Cey. Garvey and Cey were the power-hitting run producers. Lopes was the base-stealer. Russell was the light-hitting shortstop with a good glove.

Together, they went to the World Series four times from 1974 to 1981. They lost the first three times, but finally won it all against the Yankees in their final year together. In that 1981 series, the Dodgers came back from two games down to sweep the final four games. Cey was beaned in the head by Goose Gossage in Game 5, but returned to play in Game 6. He hit .350/.458/.500 and was named co-MVP of the series along with Pedro Guerrero and Steve Yeager.

Cey was well known as “The Penguin.” If you’ve ever seen him play, you know why. He looked like a human penguin, with short legs and a beefy caboose and muscular thighs. His mustache was pure-1970s gold. From 1974 to 1981, he averaged 24 homers and 85 RBI per year and made the NL all-star team six times.

In 1977, Cey was part of another record-setting foursome. He hit 30 home runs for the only time in his career. This coincided with 30-homer seasons from teammates Steve Garvey, Dusty Baker and Reggie Smith, making them the first quartet of teammates to hit 30 or more homers in a season.

In 1983, Cey was traded to the Chicago Cubs, where he played four seasons. He was then traded to the Oakland Athletics and finished out his career with one final season in 1987. Like many third basemen over the years, Cey had little support for the Hall of Fame, receiving just 1.9 percent in his one year on the ballot.

MLB History Robin Ventura (#18)

“Oh, no. You saw what happened, Dan.”—Robin Ventura, when asked by Dan Patrick if he wanted a rematch with Nolan Ryan.

Might as well get it out of the way early. Yes, 25 years ago Robin Ventura made the ill-fated decision to charge the mound on Nolan Ryan after getting hit by a pitch. He dropped his bat, threw down his helmet and ran towards Ryan. Likely expecting a typical baseball slap fight, Ventura was probably very surprised when Ryan grabbed him in a headlock and pummeled him in the face repeatedly.

Much has been made of the 20-year age gap between Ventura, who was 26, and Ryan, who was 46, but really, did that matter when it was Nolan Ryan? He’s the John Wayne of baseball. Heck, a 66-year-old Nolan Ryan could probably still throw a substantial punch.

That moment has overshadowed Ventura’s impressive career. Before playing professionally, he was an excellent amateur player. He had a 58-game hitting streak for Oklahoma State. He was on the 1988 gold medal-winning U.S. Olympic team and hit .409 in the tournament. His career average in college was .428, he slugged .792 and he won the Golden Spikes Award and the Dick Howser Trophy. In 2006, he was in the inaugural class of the College Baseball Hall of Fame.

As a major leaguer, Ventura played 10 years with the Chicago White Sox, showing off a good glove at third base and a strong bat. They only made it to the playoffs once in his time there, losing the ALCS to the Toronto Blue Jays in 1993. He followed his time in Chicago with three seasons with the Mets and parts of two seasons each with the Yankees and Dodgers.

Ventura’s teams made the playoffs five times in his 16-year career, but his overall postseason performance was not impressive. He hit .177/.307/.306. He did have one great moment when he hit a “Grand Slam Single” in the bottom of the 15th inning in Game 5 of the 1999 NLCS.

The bases were loaded in a tie game. Ventura launched one over the fence but the runner on first, Todd Pratt, didn’t see it leave the yard. He knew it was a game-winning hit and ran back to first to hug Ventura. Since Ventura never rounded the bases, what would have been a grand slam was just a single.

Leg injuries curtailed Ventura’s career when he was in his mid-30s. He retired as a player after the 2004 season. He was on the Hall of Fame ballot in 2010, but fell off the ballot when he received just seven votes (1.2 percent).

MLB History Darrell Evans (#17)

“No better feeling (hitting a home run) in the whole world. It is what you live for. Sometimes it is what you die for. You put one up there and it makes you feel young again.”—Darrell Evans

Darrell Evans was a man ahead of his time. When he played, batting average was king. Evans didn’t hit for a high average. His career mark is .248. Most people involved with baseball these days know that on-base percentage and slugging percentage are much better measures of the caliber of hitter than batting average. Evans was good at getting on base and had some pop in his bat.

Evans was drafted four different times as an amateur, but did not sign with any of those teams. He finally signed with the Kansas City Athletics after being drafted in the seventh round of the 1967 June Secondary draft. In December of 1968, the Atlanta Braves shrewdly claimed Evans off the Athletics roster in the rule 5 draft.

It took three years before Evans received significant playing time with the Braves and another two years before he would be a full-time player. That season, 1973, he made the NL all-star team and led the league with 124 walks. He also launched 41 home runs, scored 114 runs, and had 104 RBI. It was a 9 WAR season and easily the best of his career. He was third in the NL in WAR (Baseball-Reference), but finished 18th in NL MVP voting.

He followed that up with a 7.2 WAR season in which he again led the NL in walks, this time with 126. Then he walked 105 times in 1975, making it three 100-walk seasons in a row. He would have five such seasons in his career.

In 1976, Evans got off to a slow start and was traded to the San Francisco Giants in mid-June. He spent seven-and-a-half years with the Giants, regularly putting up .360 OBP seasons with 15-20 home runs and solid defense.

In December of 1983, Evans signed as a free agent with the Detroit Tigers. When the Tigers had their amazing 1984 season that ended in a World Series title, Evans was one of the few players on the team who didn’t have a great year. He still got on base (.353 OBP) but didn’t hit for much power (.384 SLG).

Despite being 38 years old heading into the 1985 season, Evans wasn’t done yet. He had a bounce back season when he led the AL in home runs while hitting .248/.356/.519. This year he became the first player to hit 40 homers in both leagues and the oldest player to lead the AL in dingers.

Evans had two more above average seasons before his career wound down with two subpar seasons in his early 40s. He retired with 1605 career walks, 12th all-time. His total of 3828 hits plus walks is 56th all-time.

MLB History Sal Bando (#16)

“I was a leader by example and not by talking. You don’t tell a (Reggie) Jackson, a (Jim) Hunter, or a (Joe) Rudi what to do. You lead by example, by giving 100 percent, by giving a continuous effort. A successful individual is one who is dedicated, on and off the field.”—Sal Bando

The Oakland A’s dynasty in the early 1970s had some fascinating personalities, including Reggie Jackson, Catfish Hunter, Vida Blue, Rollie Fingers and Joe Rudi. They were a product of the times and west coast location, with long hair and mustaches. When they faced the short-haired, clean-shaven Cincinnati Reds in the World Series, it was called “the hairs against the squares.”

On a team with numerous talented players, Sal Bando was considered by many to be the glue that kept them together. He’d been a winner even before making it to the big leagues. In college, at Arizona State, he led the Sun Devils to the 1965 College World Series championship team. On a team that had nine players drafted by major league teams, he was named the Most Outstanding Player in the tournament.

The Kansas City Athletics drafted Bando in the sixth round of the first ever MLB draft in 1965. He played 11 games in the big leagues in 1966 and 47 games there in 1967. That offseason, the Athletics moved from Kansas City to Oakland.

With the move to Oakland, Bando became a full-time starter for the first time. Over the next nine seasons he would play an average of 157 games per year, hitting .256/.360/.422 with 81 runs, 21 homers, and 88 RBI per season. He averaged 5.6 WAR per season during this stretch. By Wins Above Replacement, he was one of the five best players in baseball. In May of 1969, manager Hank Bauer named Bando team captain. He would hold the title for the rest of his career with the A’s.

In 1971, their third year in Oakland, the A’s made it to the postseason for first time since 1931. They lost in the ALCS to the Baltimore Orioles, but bounced back to win the World Series the next three seasons. Bando was an all-star all three years and finished in the top five in AL MVP voting in two of them.

The A’s made the playoffs again in 1975, but lost in the ALCS to the Boston Red Sox. The following year was a nasty one in Oakland. Seven players, Bando included, refused to sign their contracts in the hopes they would become free agents at the end of the season. A’s owner Charlie Finley responded by cutting their salaries the maximum 20 percent. A standoff ensued and the A’s players voted to strike.

Finley finally gave in and no games were forfeited, but the relationship between Bando and Finley was irreparably damaged. He became a free agent after the 1976 season and signed with the Milwaukee Brewers. By this time he was 33 years old and on the downside of his career. He played in just 110 games per year and averaged 1.9 WAR per season during his five years with the Brewers.

When his name came up on the Hall of Fame Ballot in 1987, Bando received just three votes. It was a ridiculously low total for a player who had been among the best in the game for a decade. Bando got his due with the Hall of Stats, which is an alternative Hall of Fame based on a mathematical formula that determines the best players in the game’s history. Based on the Hall of Stats criteria, Bando is the 14th best third baseman of all-time.

MLB History Ken Boyer (#15)

“He was the boss of our field. He was the guy everybody looked up to. He was the guy who really filled that role, if that role needed to be filled.”—Tim McCarver, about Ken Boyer

After signing with the St. Louis Cardinals just after graduating from high school in 1949, it took Ken Boyer six years to get to the big leagues. The first three years were spent in the minor leagues, after which Boyer spent two years with the Army during the Korean War.

In his first year back from military service, Boyer had a strong season with the Houston Buffaloes, a Double-A affiliate of the Cardinals. That earned him a promotion to the big leagues in 1955 as the replacement at third base for Ray Jablonski.

After a so-so rookie year, Boyer was an all-star for the first time in 1956 when he hit .306/.347/.494 and banged out 26 home runs and 98 RBI. It was the first of seven all-star seasons. He had successfully avoided a sophomore slump. Unfortunately, he couldn’t avoid the junior slump. In 1957, he was a below average hitter but was still good enough with the glove to be worth 3.6 WAR.

Boyer came into his own in 1958 with a .307/.360/.496 season that included 101 runs scored, 23 homers, and 90 RBI. He was worth 6.0 WAR and won his first of five Gold Gloves. This was the start of a seven-year stretch during which Boyer averaged 6.4 WAR per season and was an all-star six straight years.

His best season was 1964 when he led the NL in RBI and was named MVP of the league. The Cardinals made it to the World Series and Boyer had a grand slam in Game Four to lead the Cardinals to a 4-3 victory. He also had three hits in the series-clinching Game Seven win.

In that World Series, Ken’s brother Clete Boyer played for the Yankees. They both homered in Game Seven, which is the only time in MLB history that two brother have homered in a World Series game. Ken and Clete had an older brother named Cloyd who played in the big leagues for five seasons. There were also four other Boyer brothers who played in the minor leagues. The Boyer family had 14 kids. Seven of them played professional baseball.

Back problems began to plague Boyer in 1965. He spent one last season in St. Louis before being traded to the New York Mets, but his career was on the downside. From 1965 to 1969, he played an average of 102 games per year and averaged just 1.3 WAR per season.

Despite the support of teammates Tim McCarver and Stan Musial, Boyer didn’t get much traction in Hall of Fame voting. He was on the ballot for five years from 1975 to 1979, but never received even 5 percent of the vote. He was put back on the ballot in 1985 and peaked at 25.5 percent before his 15 years of eligibility expired in 1994.

MLB History Buddy Bell (#14)

“It’s amazing what you can do in this game with a heart and a brain.”—Buddy Bell

Based on the Fangraphs metric for defense, Buddy Bell is the fourth-best defensive third baseman in baseball history. Above him on the list are Brooks Robinson, Adrian Beltre, and Clete Boyer. Bell’s defense was acknowledged with six Gold Glove Awards. He also made the AL all-star team five times.

Bell played the first seven years of his career with Cleveland. He was generally a 3 to 4 WAR player during this stretch and only made the all-star team once. Despite being strong on defense, he couldn’t wrestle the Gold Glove from Brooks Robinson, who is the best-fielding third baseman the game has ever known.

Prior to the 1979 season, Bell was traded to the Texas Rangers for Toby Harrah and had the best season of his career. His offensive numbers weren’t spectacular. He hit .299/.327/.451, which was eight percent above average after league and ballpark effects are taken into account. His glove was elite, though, and he had a 6.9 WAR season.

That was the start of Bell’s peak. From 1979 to 1984, he hit .301/.358/.445, won six consecutive Gold Gloves, made the all-star team four times, and averaged 6 WAR per season. By Baseball-Reference WAR, he was the fourth best player in baseball during this time.

At this point, Bell was 32 years old and had accumulated 55.5 WAR (Fangraphs). That is the 65th best mark in MLB history for players through the age of 32. He was coming off an all-star season in which he won the Gold Glove and Silver Slugger.

Unfortunately, Bell did not age well. He started slowly in 1985 and was traded to the Cincinnati Reds, where he wasn’t much better over the rest of the season. He had a bounce back year in 1986, then finished out his career as a below average player for the next three seasons.

In one year on the Hall of Fame ballot, Bell received 1.7 percent of the vote. He was appreciated in Texas, though, and entered the Rangers Hall of Fame in 2004, along with pitcher Fergie Jenkins and broadcaster Tom Vandergriff.

MLB History Frank “Home Run” Baker (#13)

“It’s better to get a rosebud while you’re alive than a whole bouquet after you’re dead.”—Home Run Baker

It’s easy to look at Home Run Baker’s career total of 96 round-trippers and wonder how he ever got that nickname. Well, it was a different time. Baker led the AL in home runs four straight years from 1911 to 1914. In those four years, he hit 11, 10, 12 and 9 long balls, for a total of 42. Within 10 years, Babe Ruth would hit 54 home runs in a single season, 12 more than Home Run Baker hit in four league-leading seasons.

Legend has it that Baker earned the nickname “Home Run” when he hit two dingers against the New York Giants in the 1911 World Series. Both of his home runs were key to the Athletics winning games. The first came off Rube Marquard in the sixth inning of Game Two of the series. The score was tied 1-1 and Baker’s two-run shot was enough for the A’s to win the game.

The very next game, Baker hit a clutch, game-tying home run off the great Christy Mathewson. The A’s went on to win the game in 11 innings. This is the legend of how Frank Baker became “Home Run” Baker, but is it really true?

Nope. According to this SABR article, Baker was referred to as “Home Run” Baker in the Philadelphian North American in 1909, two years before his home run heroics in the 1911 World Series. In that North American article, Baker’s previous exploits were detailed: “Baker’s work has possibly been the most spectacular. On three occasions he has won close games with home runs, while his fielding inspires the belief that [Connie] Mack will have the best man at the corner since the days when Lave Cross was good.”

So Baker was Home Run Baker before his big World Series against the Giants in 1911. Once he got the name, he held it for life. Despite being known for his home runs, Baker was a good all-around hitter, finishing his 13-year career with a 134 wRC+. At his best, he could hit home runs, get on base at a good clip, and steal bases.

During the last six years of his career, Baker played for the New York Yankees. He was teammates with Babe Ruth in 1921 and 1922. While the Babe was setting home run records every year, Baker pointed out that the lively ball made a difference, saying, “I don’t like to cast aspersions, but a Little Leaguer today can hit the modern ball as far as grown men could hit the ball we played with.”

Years after his career ended, Baker appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot. He didn’t get enough support for induction in 11 years on the BBWAA ballot, but did make the Hall of Fame through the Veterans Committee in 1955.

MLB History Graig Nettles (#12)

“Some kids dream of joining the circus, others of becoming a major league baseball player. I have been doubly blessed. As a member of the New York Yankees, I have gotten to do both.”—Graig Nettles

It was easy for Nettles to get lost among the big names he played with as a member of the New York Yankees in the 1970s. Those teams had the bombastic Reggie Jackson, always craving the spotlight, and the much more serious Thurman Munson, who kept the team grounded. Mickey Rivers was an eccentric in the outfield, often playing alongside the perpetual hard ass, Lou Piniella.

Nettles took up his spot at third base, where he flashed a good glove and a power bat. When the New York Yankees won back-to-back World Series in 1977 and 1978, Graig Nettles was their best position player the first year and second-best the second year (based on Baseball-Reference WAR). He was also usually good for a clever quote when the madness of the “Bronx Zoo” Yankees bubbled up.

As good as Nettles was in 1977 and 1978, he was at his very best in 1976, when he was worth 8 WAR. That year, he led the AL in home runs, had a 135 wRC+ and was very good with the glove. This was during a ten-year stretch from 1970 to 1979 when Nettles averaged 5.5 WAR per season. No AL player had more WAR than Nettles in the 1970s and only two NL players topped him (Joe Morgan and Johnny Bench).

Nettles was most famous for his time with the Yankees. He wrote a book about his baseball career and, in particular, the 1983 season. Appropriately, it’s called Balls. Before playing with the Yankees, he had three partial seasons with the Twins and three more in Cleveland. After leaving the Yankees following the 1983 season, Nettles played for the Padres, Braves, and Expos.

Nettles blasted 390 home runs in his career, good for ninth all-time among third baseman. He’s 16th among third sackers in RBI and sixth at the hot corner in the Fangraphs defensive metric. Despite his accomplishments, he never got much support in Hall of Fame voting, topping out with 7.9 percent of the vote in year three, then falling off the ballot after year four.

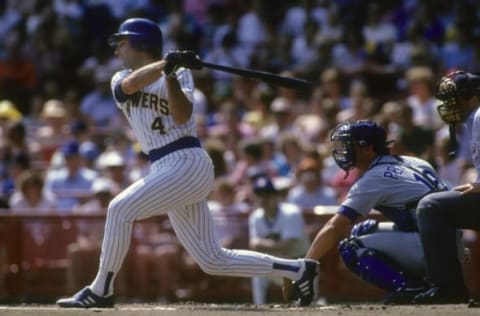

MLB History Paul Molitor (#11)

“Complaining is like vomiting. You might feel better after you get it out, but you make everybody around you sick.”—Paul Molitor

There must have been something in the water near St. Paul, Minnesota, in the 1950s. Paul Molitor was born there in 1956, roughly five years after Dave Winfield and 15 months after Jack Morris. Molitor and Morris squared off against each other occasionally in youth leagues. With the induction of Morris into the Baseball Hall of Fame this summer, there will be three Hall of Fame St. Paul natives born within five years of each other in Cooperstown.

Winfield and Molitor both went to the University of Minnesota. After three seasons playing for the Golden Gophers, Molitor was drafted by the Milwaukee Brewers with the third overall pick of the 1977 Amateur Draft. The first two picks that year were also productive major leaguers, Harold Baines and Bill Gullickson.

It only took 64 minor league games for Molitor to make his way to the big leagues. He joined the Brewers in 1978 and was good enough his first year to finish second in AL Rookie of the Year voting behind Lou Whitaker. Two years later he had his first of seven all-star seasons.

After making the all-star team in 1980, Molitor had a rough year in 1981. He was moved from his regular position at second base to center field. He didn’t hit. He was injured. And there was the player’s strike. It was the worst season of his career to that point. One bright spot was the Brewers making the playoffs for the first time in franchise history.

Molitor bounced back in 1982 with the best season of his career, hitting .302/.366/.450 and leading the league in plate appearances and runs scored. He was worth 6.2 WAR (Baseball-Reference) and finished 12th in AL MVP voting. He continued his hot hitting in the Brewers’ five-game victory over the California Angels in the ALCS, then hit .355/.394/.355 in their seven-game loss to the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series.

That offseason, Molitor signed a five-year, $5.1 million contract. Life seemed good, but it was not without problems. A wrist injury caused his numbers to drop that season. Off the field, his name and four others came out during a trial involving a cocaine dealer. The Brewers went from division leaders to fifth place.

Molitor played with the Brewers through the 1992 season, 15 years in all, but they never made it back to the postseason during the rest of his tenure. He made the all-star team four more times as a Brewer and was particularly good in 1991 when he led the league in hits, runs and triples. He also had a 39-game hitting streak in 1987.

After the 1992 season, he signed as a free agent with the Toronto Blue jays and had two more all-star seasons. He was a big part of the 1993 World Series winning team. After banging out nine hits in the six game ALCS, Molitor was 12-for-24 with 10 runs and eight RBI in the World Series. He was named MVP for his incredible performance.

After three years in Toronto, Molitor returned to Minnesota to play for his hometown Twins. He led the league in hits his first year with the Twins. More importantly, on September 16, 1996, he hit a triple into right field to reach the 3000 hit plateau. He was the first player in MLB history with a triple for his 3000th hit.

Coincidentally, Molitor reached the milestone exactly three years to the day after Dave Winfield picked up his 3000th hit. Winfield had done it for the Twins also and the two players made history by being the first to players born in the same town to have 3000 hits. Well done, St. Paul, Minnesota, well done.

MLB History Scott Rolen (#10)

“I’m a baseball player. I’m also a guy who mows his lawn and plays with his dog.”—Scott Rolen

Scott Rolen was a two-sports star at Jasper High School in Jasper, Indiana. As a senior, he was the runner-up for Mr. Basketball in Indiana, an honor that recognizes the top high school basketball player in the state. The winner that year was Maurice “Kojak” Fuller. Two years earlier, future NBA player Glenn Robinson was Mr. Basketball.

While Rolen came up short on the Mr. Basketball title, he was named Mr. Baseball during the spring. Despite his baseball success, Rolen planned to go to the University of Georgia to play basketball. When the Phillies drafted him in the 1993 Amateur Draft, he signed with them.

Rolen got into 37 games in 1996, but didn’t get enough plate appearances to exhaust his rookie eligibility. In 1997, he hit .283/.377/.469 with 93 runs, 21 homers, 92 RBI, and 16 steals. It was a 4.5 WAR season and good enough to earn him the NL Rookie of the Year Award.

He followed up his strong rookie season with four more seasons that were as good or better. From 1997 to 2001, he averaged 5.2 WAR per year. He also won the Gold Glove Award three times. During this stretch, the Phillies were only competitive in 2001, when they finished two games out in the NL East.

In 2002, with free agency looming, Rolen demanded a trade. He didn’t think the Phillies front office was committed to putting a championship caliber team on the field and he clashed with manager Larry Bowa. Just before the trade deadline, the Phillies dealt him to the Cardinals for Placido Polanco, Mike Timlin and Bud Smith. He signed an 8-year, $90 million deal with the Cardinals later that year.

Rolen continued his strong play with the Cardinals. He was an all-star each year from 2002 to 2006 and continued picking up Gold Glove Awards. His best season was in 2004, when he hit .314/.409/.598, with 109 runs, 34 homers, and 124 RBI. He finished fourth in NL MVP voting behind one of Barry Bonds’ ridiculous seasons, a monster year by Adrian Beltre, and a typical Albert Pujols performance.

He helped the Cardinals make the World Series in 2004 and 2006. They were swept by the Red Sox in the 2004 series but won the 2006 series over the Detroit Tigers. In between, the 2005 season was a lost one for Rolen because of an injured shoulder suffered when he collided with Hee-Seop Choi of the Dodgers.

The shoulder injury plagued Rolen again in 2007, cutting his season short. That offseason, he was traded to the Blue Jays for Troy Glaus. He lasted about a year-and-a-half in Toronto before being traded to the Reds in 2009 for Edwin Encarnacion, Josh Roenicke and Zach Stewart. He had one good year with Cincy and two not-so-good years and that was that.

Rolen was on the Hall of Fame ballot for the first time last year. Despite ranking 11th all-time among third basemen in Fangraphs WAR, he only received 10.2 percent of the vote. Based on Jay Jaffe’s JAWS system, he was the eighth-best player on the ballot but finished 17th in vote percentage.

MLB History Ron Santo (#9)

“The last thing I want is to die and then be put in the Hall of Fame. It’s not because I won’t be there to enjoy it, exactly. It’s because I want to enjoy it with family and friends and fans. I want to see them enjoy it.”—Ron Santo

Ron Santo played during a very difficult period for hitters. His career spanned from 1960 to 1974. During this 15-year stretch, Santo hit .277/.362/.464. Even though his rate stats may not look all that impressive, for the time and place he played, Santo was 26 percent better than average on offense (126 wRC+).

By comparison, Ray Lankford played from 1990 to 2004, exactly 30 years after Santo. Langford played during a much better era for hitters and hit .274/.371/.502. His on-base percentage was nine points higher than Santo’s and his slugging percentage was 38 points higher. Despite this difference, they had the same wRC+.

When adjusted for league and ballpark effects, Santo’s .277/.362/.464 was the equal offensively to Langford’s .274/.371/.502. Of course, Hall of Fame voters didn’t know about wRC+ (it hadn’t been invented yet) and have often had trouble with league and ballpark effects. Santo was on the BBWAA Hall of Fame ballot for 15 years and topped out at 43.1 percent in 1998.

By Fangraphs WAR, Ron Santo was the third-best third baseman in MLB history when he retired. Only Eddie Mathews and Brooks Robinson were more valuable. A half-dozen third baseman have passed him since, dropping him to ninth, which is still impressive.

Santo did things on the field that weren’t appreciated then like they are now. He led the league in walks four times and twice led the league in on-base percentage, but no one wins a batting title for leading that category.

That’s not to say he wasn’t recognized during his career. He won five Gold Glove Awards and was named to the all-star team nine times. In retirement, he was recognized in 1999 when he was named to the Cubs All-Century Team.

In 2003, the Cubs retired his jersey number (#10), making him the third Cub to receive the honor. A year later, he was inducted into the inaugural class of the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association Hall of Fame for his performance at Franklin High School in Seattle.

Santo appreciated these honors while continuing to be optimistic about the Hall of Fame. He didn’t get close with the BBWAA, but as the statistical revolution took hold his case was bolstered by a better assessment of his value with the bat and glove during a tough hitter’s era. He finally made it when the Veterans Committee selected him for enshrinement in 2012. Unfortunately, it two years after his death.

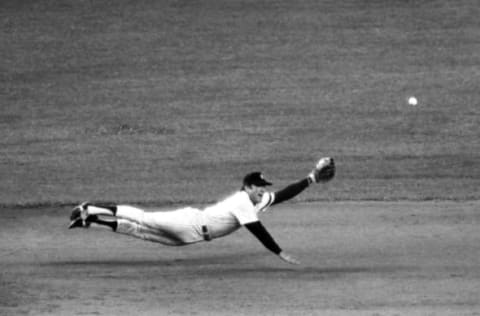

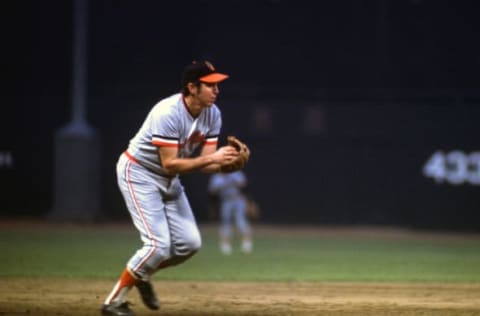

MLB History Brooks Robinson (#8)

“I could field as long as I can remember, but hitting has been a struggle all my life.”—Brooks Robinson

With a 104 wRC+, Brooks Robinson is the weakest hitter on this list of the 25 greatest third basemen in MLB History. Of course, his glove was the best ever for a third baseman and it’s not close. The only position player rated higher on defense by Fangraphs is shortstop Ozzie Smith, the “Wizard of Oz.”

Just below Robinson is shortstop Mark Belanger, who played alongside Brooks for many years in Baltimore. Belanger became a regular at shortstop for the Orioles in 1968. Robinson’s last full-time season was 1975. That must have been one tough infield to get a ball through when they were on the field together.

During this eight-year stretch, the difference between the Orioles’ Total Zone numbers and the second-best team on defense was about the same as the difference between the second-best team and the eighth-best team. The Orioles dominated on defense.

Before Belanger arrived to play next to Robinson, Robinson had been in the big leagues for a decade. He came up in the 1955 season as an 18-year-old, but only played in six games. It would take another three years before he had his first full season and two more years before he solidified his spot in the lineup for good.

From 1960 to 1974, Brooks Robinson was an all-star every year. He also won the AL Gold Glove Award every year. The combination of terrific defense and above average offense made him worth an average of 5.1 WAR per season over a 15-year period. He wasn’t a top-notch hitter, but during this time he was about 10 percent better than average on offense.

As a hitter, Robinson was roughly a 70 runs, 15-20 HR, 80 RBI per season guy. He had five seasons with more 20 or more home runs and two seasons with 100 or more RBI, including the 1964 season when he led the league in ribbies and won the AL MVP Award.

He was a part of six Orioles teams to make the postseason, including four World Series teams. They won twice during his time with the franchise and his performance in the 1970 series earned him the MVP Award. The plays he made in that series wowed the baseball world.

Robinson retired after the 1977 season and the Orioles immediately retired his jersey number five. In his first year of eligibility, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. When The Sporting News put out their list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players in 1999, Robinson was number 80. That same year, fans voted for the MLB All-Century Team and Robinson was one of the two third basemen they chose, along with Mike Schmidt.

MLB History Chipper Jones (#7)

“I think baseball has such a way of humbling you. You can go 20-for-20, and before you know it, you’re going to go through an 0-for-30. It has that way of knocking you back down to earth.”—Chipper Jones

The number eight guy on this list, Brooks Robinson, had most of his value with his glove. Chipper Jones is the opposite. He was a bat-first third baseman, whose glove was a liability during his career.

Despite his glove, he was still good enough with the bat to be the seventh best third baseman of all-time, and not that far off from the number four guy on this list. You could say he’s on a tier of four third baseman ranked fourth through seventh who could easily be moved around a bit depending on your preference.

The Atlanta Braves took Jones with the first overall pick of the 1990 draft, which included another Hall of Fame caliber player, Mike Mussina, who was taken 20th in the first round. Jones spent three years in the minor leagues from 1990 to 1992, got a cup of coffee in the big leagues in 1993, then missed the entire 1994 season with a torn ACL.

Jones was back on the field in 1995 and his career took off. He was second in NL Rookie of the Year voting behind Hideo Nomo that year and made the all-star team for the first of eight times the following year. In 1999, he won the NL MVP Award when he hit .319/.441/.633, with 116 runs, 45 homers, 110 RBI, and 25 steals.

During a 15-year stretch from 1995 to 2009, Jones averaged 97 runs, 28 homers and 96 RBI per year while hitting .307/.406/.540. He was a big part of the Atlanta Braves winning the NL East 11 years in a row. They made it to the World Series three times and came away with one championship. In 93 postseason games, Jones hit .287/.409/.456.

Among the more impressive accomplishments in Jones career, he is only the second switch-hitter in history with at least 5000 plate appearances who hit over .300 from both sides of the plate. Frankie Frisch was the other. He said he learned to switch hit while batting against his father in the yard. He would imitate the lineup of whatever team was on the Saturday game of the week. When a lefty came up, he’d hit left. When a righty came up, he’d hit righty.

Another impressive switch-hitting feat by Jones puts him in the company of Mickey Mantle. They are the only switch-hitters in MLB history to have a .400 on-base percentage, a .500 slugging percentage, and hit 400 career home runs.

Jones retired at the age of 40 after a final all-star season in 2012. He was voted into the Hall of Fame last year in his first year of eligibility and will be on the stage in Cooperstown this summer, along with Vladimir Guerrero, Jim Thome, Trevor Hoffman, Jack Morris and Alan Trammel.

MLB History George Brett (#6)

“If a tie is like kissing your sister, losing is like kissing your grandmother with her teeth out.”—George Brett

It’s interesting to look back at the 1971 MLB draft. There were three players drafted in the first round who went on to have good MLB careers: Frank Tanana, Jim Rice and Rick Rhoden. They were drafted 13th, 15th and 20th respectively. In the second round, with the 29th overall pick, the Kansas City Royals drafted George Brett. Somehow, 28 players were drafted before one of the greatest third basemen in MLB history. Taken immediately after George Brett? Mike Schmidt, another man on the greatest third basemen list.

It only took Brett a couple years to reach the major leagues. He finished third in AL Rookie of the Year voting in 1974, behind Mike Hargrove and Bucky Dent, but was a below average hitter on the season. That would be the last time he was below average offensively for the next 16 years.

From 1975 to 1990, Brett hit .314/.382/.511, made the all-star team 13 times, won three batting titles, a Gold Glove, and was the AL MVP in 1980. He led the league three times in hits, triples, and slugging percentage. He also won three Silver Slugger Awards.

The 1980 season was peak George Brett. He flirted with a .400 average for most of the summer. He did it in an unusual way. Rather than getting off to a hot start where he was hitting over .400 early in the season before fading away, he actually got off to a very slow start. He hit just .259 in April and only got his average over .300 on the last day of May because he had a 3-for-4 game.

When the calendar flipped to June, Brett heated up. He had four three-hit games in a week and was up to .337 on June 10 when an ankle injury sidelined him. He came back in July and just kept on hitting. By the end of the month, he was up to .390.

Brett hung around the .390 mark for the first half of August, then put together another hot streak when he went 32-for-64 in 16 games from August 10 to August 26. Heading into September, he was hitting .403 and the country was watching. No one had hit .400 since Ted Williams in 1941.

A 4-for-16 run in five games early in September dropped Brett to .396, then he missed another 10 days with an injury. He came back on September 17 and had six hits in his next 12 at-bats. At the end of the night on September 19, he was hitting .400 with two weeks left in the season.

Every baseball fan knows what happened next. Brett couldn’t stick at .400 and finished the year at .390. In his last 13 games, he hit .304/.370/.674. What’s interesting about those last 13 games is that his Batting Average on Balls In Play (BABIP) was just .220. During the season, his BABIP was .368 and his career BABIP was .307, so it’s possible, maybe likely, that he had at least a little bit of bad luck during those last two weeks.

Ultimately, the difference between Brett hitting .390 and .400 that season was five hits. If five balls had dropped in somewhere along the way, Brett would have ended the long drought of .400 hitters. Remember that this is a guy who only hit .259 in April. Over the last five months of the season, Brett hit .408. It was an incredible year.

Brett retired after the 1993 season. The Royals retired his jersey number 5 in 1994. In 1999, he was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year on the ballot. He was also ranked number 55 on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players.

MLB History Adrian Beltre (#5)

“I’m not perfect. Nobody’s perfect. But I love baseball and I love to play hard.”—Adrian Beltre

Adrian Beltre is a national treasure. His antics on the field with teammates, opposing players and umpires have brought pleasure to baseball fans for many years. He’s incredibly fun to watch. He’s also been an incredibly good player in his career.

Beltre was just 17 years old when he made his professional debut in the Los Angeles Dodgers minor league system and just 19 years old when he made it to the major leagues in 1998. During his first five full-time seasons in the big leagues, he didn’t look like a future Hall of Famer. He hit .265/.323/.432 during this stretch, which was right around league average offensively. He was good on defense, though, which made him an above average player (averaging 2.7 WAR per season).

Then Beltre exploded in 2004 with a 9.7 WAR season that was good enough for second in NL MVP voting. Only Barry Bonds, with a ridiculous .362/.609/.812 batting line, prevented Beltre from winning the award. It’s one of the greatest seasons ever for a third baseman.

Coming off that great season, Beltre signed a five-year, $64 million contract as a free agent, joining the Seattle Mariners. He signed one day after the Mariners added free agent first baseman Richie Sexson. They were supposed to add big time power to a week M’s lineup.

Beltre’s years in Seattle are looked upon as a bust, but he was better than people remember. He averaged 4.2 WAR per year with the M’s. He didn’t have the huge offensive numbers, but his glove at third base was so good that he was one of the team’s better players.

Of course, Beltre’s game went to another level after leaving the Emerald City. He played one year in Boston before heading to Texas to play with the Rangers. From 2010 to 2016, he averaged 86 runs, 28 homers and 95 RBI, with a .310/.359/.521 batting line. He was a four-time all-star and three-time Gold Glove winner during this seven year stretch.

Beltre missed time due to injuries last year, but was still a well above average player. He’s missed time again this year, but is still hitting .324/.380/.434 at the age of 39. He already has over 3000 career hits and 464 career home runs. He should be a lock for Cooperstown.

MLB History Wade Boggs (#4)

“One guy that I wish was here right now, Ted Williams, helped me so much, our long talks, not about hitting but about fishing, one of Ted’s passions, and I wish he was here today to share this with me because I owe so much to Ted Williams”—Wade Boggs

When Wade Boggs was in high school, his father gave him the Ted Williams book The Science of Hitting. One of the key beliefs of Williams was to not swing at bad pitches. Boggs would follow this advice religiously over his career. He had four seasons with more than 100 walks and led the league in on-base percentage six times.

Boggs wasn’t considered much of a baseball prospect coming out of high school. He had a scholarship offer to play football at the University of South Carolina. When the Red Sox drafted him in the seventh round of the 1976 draft, Boggs eschewed football for his first love, baseball.

Interestingly enough, the seventh round of the 1976 had two other players who had good major league careers besides Boggs. One was Willie McGee, an outfielder who played 18 years in the bigs and won the 1985 NL MVP Award when he led the league in hitting with a .353 average. The other was Hall of Fame shortstop Ozzie Smith.

After choosing baseball over football, Boggs began a long minor league grind. He played at the Low-A level for a year, then A-ball, then Double-A. The Red Sox had him repeat Double-A before he was moved up to Triple-A. Again, the Red Sox made him repeat the level. He spent his last five years in the minor leagues hitting over .300 with an on-base percentage around .400.

Finally, in 1982, Boggs got his shot in the major leagues. He hit .349/.406/.441 in 104 games, which was good enough for third place in AL Rookie of the Year voting behind Cal Ripken, Jr. and Kent Hrbek.

Boggs quickly made up for the big league time he’d missed while being kept in the minor league. From 1983 to 1996, he banged out an average of 184 hits per year with a .332/.422/.450 batting line. He averaged 6 WAR per season, was an all-star 12 times, a Silver Slugger eight times, a batting champion five times, and won two Gold Glove Awards. He was also reportedly a world-class beer drinker.

When he retired, Boggs had over 3000 hits and 1400 walks. Since 1939, the first year of Ted Williams’ career, Wade Boggs is fourth all-time in batting average. Only Ted Williams, Tony Gwynn, and Stan Musial are higher. He’s also ninth in on-base percentage since that time. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 2005.

MLB History Eddie Mathews (#3)

“It’s only a hitch when you’re in a slump. When you’re hitting the ball its called rhythm.”—Eddie Mathews

Growing up in Santa Barbara, California, Eddie Mathews used to tell the story about how his parents helped him become a great baseball player. He said, “My mother used to pitch to me, and my father would shag balls. If I hit one up the middle close to my mother, I’d have some extra chores to do. My mother was instrumental in making me a pull hitter.”

Coming out of high school, Mathews could have played college football, but chose to sign with the Boston Braves a few minutes after midnight on his graduation night. It didn’t take long for him to take over the starting third baseman’s job with the Braves in 1952, when he was just 20 years old. He hit 25 home runs and finished third in NL MVP voting that year, tied with Dick Groat and behind pitchers Joe Black and Hoyt Wilhelm.

That year was just a taste of what was to come. Mathews led the NL in home runs as a 21 year old, while also banging out 135 RBI. He was an all-star for the first of a dozen times and finished second in NL MVP voting to Roy Campanella. This was the first of a 13-year stretch during which Mathews averaged 100 runs, 35 homers, 98 RBI, and a .277/.385/.528 batting line. He averaged nearly 7 WAR per season for 13 years.

The left-handed hitting Mathews formed a great righty-lefty tandem in the lineup with Hank Aaron. Mathews not only popped 30-45 homers per year, he also regularly walked 90 or more times in a season. He led the league in home runs twice and in walks four times.

Mathews was known for his toughness. When his Braves got into a beanball war with the Dodgers in 1957, the 6-foot-1, 190-pound Mathews squared off with the 6-foot-5, 190-pound Don Drysdale, another player known for not backing down to anyone.

The Braves played in three different cities during Mathews’ career. They were in Boston his first year, moved to Milwaukee his second year, then moved to Atlanta prior to the 1966 season, which would be his 14th year in the major leagues. He struggled a bit that season compared to his previous production and was traded to the Houston Astros in December.

Playing in Houston did nothing to prevent Mathews’ mid-30s fade. He was traded to the Detroit Tigers in August of 1967. The Tigers brought him back for the 1968 season but he only played 31 games that year and his career was over.

When Mathews retired after the 1968 season, he was 16th all-time in WAR. Of course, baseball writers didn’t know that because it hadn’t yet been developed. They did know that he had 512 home runs, sixth all-time when he retired. Despite this, he only received 32.3 percent of the vote in his first year on the ballot for the Baseball Hall of Fame. He gradually moved up in the voting and was finally selected in his fifth year on the ballot.

MLB History Alex Rodriguez (#2)

“I’m a terrible singer. I feel lucky to play baseball. You can’t be gifted in everything.”—Alex Rodriguez

It was hard to know if Alex Rodriguez should be included on this list of the top 25 third basemen in MLB history. He was already included on the top 25 shortstops list at number two, behind Honus Wagner. Ultimately, because he played over a thousand games and more than ten thousand innings at both shortstop and third base, he’s included on both lists.

Rodriguez played shortstop for the first 10 years of his career, seven of those with the Seattle Mariners and three with the Texas Rangers. Those years were covered more than adequately on the top 25 shortstops list. Here we’ll look at Alex Rodriguez, the third baseman.

Prior to the 2004 season, Alex Rodriguez was traded by the Rangers to the Yankees for Alfonso Soriano and a player to be named later. That player turned out to be Joaquin Arias. According to this ESPN article from 2004, the Rangers had their choice from a group of five prospects. Four of those prospects were Ramon Ramirez, Rudy Guillen, Joaquin Arias and Robinson Cano. Imagine how different that trade would look if the Rangers added Soriano AND Cano.

The trade was a big deal, not only because Rodriguez was a terrific player, but also because of the size of his contract. This trade came three seasons after A-Rod had signed a 10-year, $252 million contract with Texas. As part of the deal, the Rangers agreed to pay $67 million of the $179 million left on the contract.

As a result of the trade, Rodriguez moved from shortstop, where he’d been an all-star seven times, to third base because the Yankees had The Captain, Derek Jeter, at short. Statistically, this didn’t make any sense at all. In the previous eight years, from 1996 to 2003, Alex Rodriguez was fourth defensively among the 25 shortstops with 3000 or more plate appearances. Derek Jeter was 22nd. Still, Jeter was the very popular incumbent, so he stayed at shortstop.

Rodriguez had averaged 8 WAR per year during his first eight full seasons in the major leagues with the Mariners and Rangers. In his first eight years with the Yankees, he “only” averaged 6.2 WAR per season. He also added two more AL MVP Awards to the one he already had. I mean, really, that’s a terrific stretch of seasons, but when you’re making the money he was making, criticism is almost inevitable.

Some bad playoff series from 2005 to 2012 led to the “postseason choker” label being attached to Rodriguez. Then came a PED suspension, a bounceback season at the age of 39, and one final, sad year in which A-Rod hit .200/.247/.351 in his first 65 games before he and the Yankees “mutually” decided his playing career was over. He finished four home runs short of joining Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron and Barry Bonds in the 700-homer club.

MLB History Mike Schmidt (#1)

“I sort of ride the fence on that whole steroid era issue. I don’t have a definite opinion like some of my fellow Hall of Famers. Some of the guys were very, very adamant about a person being associated with steroids: ‘They’ll never be in the Hall of Fame. If they are, I’ll never come back.’”—Mike Schmidt

Here he is, ladies and gentlemen, the greatest third baseman in MLB history: Michael Jack Schmidt, the original MJ. Okay, not really the original MJ, but still the greatest third baseman ever.

As mentioned in the George Brett essay, Mike Schmidt was drafted in the 2nd round of the 1971 June Draft. He was taken one pick after George Brett. Two of the greatest third basemen ever were taken back-to-back. Very cool.

More from Call to the Pen

- Philadelphia Phillies, ready for a stretch run, bomb St. Louis Cardinals

- Philadelphia Phillies: The 4 players on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore

- Boston Red Sox fans should be upset over Mookie Betts’ comment

- Analyzing the Boston Red Sox trade for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen

- 2023 MLB postseason likely to have a strange look without Yankees, Red Sox, Cardinals

After the draft, Schmidt went directly from college ball to Double-A. He didn’t do much there, hitting .211/.302/.350, but the Phillies moved him up to Triple-A anyway in 1972. He did just fine in Triple-A, hitting .291/.409/.550 with the Eugene Emeralds. That earned him a September call-up at the end of the 1972 season and the starting third base job in 1973.

As a rookie in the big leagues, Schmidt really struggled. He hit .196/.324/.373 and struck out 136 times in 443 plate appearances. The notoriously passionate Philly fans got on him unmercifully. Whether it was his bad rookie year or something else, it seemed Philly fans never warmed to Schmidt during his long, productive playing career.

After his bad rookie year, Schmidt quickly became one of the top players in baseball. He led the NL in home runs and slugging percentage in 1974, then led the league in home runs again in 1975 and 1976. He would lead the league in home runs eight times in his career. He also led the league in RBI four times, walks four times, on-base percentage three times, and slugging percentage five times.

In addition to getting on base and hitting with tremendous power, Schmidt had eight seasons with double-digit steals, including a career-high 29 in 1975. He won his first Gold Glove in 1976 and would go on to win 10 in his career. He was a complete player who put up 14 straight seasons of 5 or more WAR between 1974 and 1987. He won three NL MVP Awards.

Despite his considerable accomplishments, when the Phillies lost in the NLCS three straight years from 1976 to 1978, Schmidt took some flack from the fans. He got back on their good side when the Phillies won the World Series in 1980 and Schmidt was the MVP of the series, but he was never as beloved as Tony Gwynn in San Diego, Cal Ripken, Jr. in Baltimore or Willie Stargell in Pittsburgh.

Schmidt’s last great season was 1987, when he hit 35 homers, had 113 RBI, and a .293/.388/.548 batting line. He struggled a bit in the 1988 season that ended early with a rotator cuff injury. When he was hitting .203/.297/.372 two months into the 1989 season, he decided to hang up his spikes. At the time of his retirement, his 548 career home runs were seventh all-time.

After his career ended, Schmidt received numerous accolades. The Phillies retired Schmidt’s number 20 in 1990. In 1995, he made the Baseball Hall of Fame with 96.5 percent of the vote. Four years later, he was voted by the fans as the starting third baseman on the MLB All-Century Team.

Next: Top 25 first basemen in MLB history

A statue of Schmidt was dedicated outside the third base gate at Citizens Bank Park in 2004. More recently, in 2015, Schmidt was one of the Phillies’ “Franchise Four” as voted by the fans, along with Steve Carlton, Richie Ashburn and Robin Roberts.