MLB Narrative History: The Cleanest Black Sox

In the biggest scandal in the history of the game, some of the Black Sox were much cleaner than others

It is reasonable to argue the worst scandal in the history of American sports is the Black Sox scandal of 1919. The facts of the case are pretty well-known, even today. Eight members of the Chicago White Sox allegedly conspired with gamblers – some of them allied with Arnold Rothstein, a brilliant, rotten man – to throw the World Series to the inferior Cincinnati Redlegs. Rothstein was ultimately shot to death at a poker game in 1928, but by then, all the Dirty Sox had been thrown out of major league baseball.

This expulsion occurred in 1920, and had been ordered by baseball’s first commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a man who later fought hard behind the scenes to keep African-Americans out of MLB. Luckily for the history of the nation, Landis went to his grave before he could affect Branch Rickey’s decision to hire Jack Roosevelt Robinson to work for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Photographers also rejoiced. Seldom has a man taken so miserable a portrait as Landis.

Yet when Landis threw the eight Black Sox out of baseball, the public – South Side Chicagoans notwithstanding – approved. The White Sox of 1919 had been, and remain with the ’27 Yankees, ’29 A’s and ’75 Reds, one of the greatest teams ever assembled. That they would throw a World Series seemed one of the great unforgivable sins. History has begun to see, however, different degrees of guilt among the awful eight, beginning most notably and completely with Eliot Asinof’s Eight Men Out in 1963.

Chick Gandil, the Pale Hose first sacker, remains the dirtiest of the infamous eight. Indeed, he proposed throwing the Series to the buzzard-gamblers circling the championship matches. Ironically, Gandil got away from the fix in the best shape. He retired to “the good life” in California.

The great Shoeless Joe Jackson remains the most puzzling of the eight. It has been well established he did receive dirty money, but he then went out and hit .375 in the ’19 Series. Later, half-drunk, he admitted to a grand jury that he “hadn’t played good baseball” during the battles with the Reds, but the question arises: Did Jackson pull one over on the gamblers?

It is debated seriously whether or not Shoeless Joe can be assigned a single thrown play during the Series. He may have “dogged it” on a fly ball that fell for a hit in game five, but it is hard to tell. No videotape. Jackson didn’t reach the ball first after it fell for a hit. Centerfielder Felsch did. Jackson played left, and had 12 hits during the Series, including the only home run, in the last game. He still stands third on the list of lifetime average leaders (.356) and remains the answer to the arcane trivia question: Who holds the record for the most hits in his last major league season? Rarely reaching base on Texas-leaguers, Shoeless Joe slammed 218 during the 1920 campaign. In October of that year he and seven fellow players were indicted.

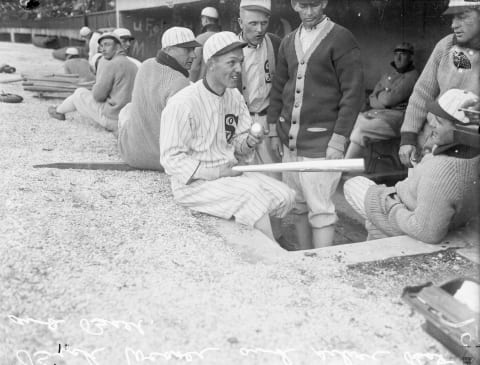

The cleanest black sox, however, were worn by Pottstown, PA, native George “Buck” Weaver, who played third for the Chisox.

Weaver’s Origins

Weaver was born in August, 1890, in a town that today may imagine it is a city, but isn’t. One hundred years ago it was a small industrial town surrounded by rich Pennsylvania farmland, a town where town kids played baseball on pavement or dirt roads, and their cousins played in fields. One imagines Weaver, a thin, strong boy moving between both venues, but looking for the little tougher town game, where he could face kids a little older, who threw harder. He had an innate quickness and could adjust.

He may have taken up the game late – at 12 or 13, rather than seven or eight – but this seems unlikely. By 1912, at 21 years of age, he hit Chicago, took 523 official at-bats for the Sox and walked only nine times. He only hit .224, but he was clearly there to swing the bat. He also swiped 12 bases. The Black Sox scandal was still years away.

Over the next several years Weaver’s batting average rose erratically toward the .300 mark that he registered in 1918. He struck out only occasionally, and in 1919, a world champion already (1917) and a seasoned veteran, he hit .296 for the team universally called the best team ever. He had 11 walks and struck out 21 times, a career low. Defensively, he was outstanding. It is reported Ty Cobb, the greatest “little ball” player ever, would not try to lay down bunts against Buckie.

The ’19 Sox weren’t a happy group, however, whatever their talent level. They felt unappreciated and underpaid, the latter with good reason.

Only Eddie Collins, the second sacker with Roberto Alomar’s impact, had a decent contract. The guy with Willie Mays’ talent (Jackson) did not; the guy with Curt Schilling’s impact (Eddie Cicotte) did not. Cicotte, who was 29-7 with a 1.82 ERA in 1919, was to become a pivotal figure in the downfall of the Black Sox. He got his hands on $10,000 of the gamblers’ money, more than anyone else. That seems to have been a simply practical decision by the gamblers. As the first pitcher in the rotation, Cicotte could have pitched three games in the scheduled nine game series. He was given his money early; the rest of the players were put off.

What Did Buckie Know and When Did He Know It?

At a minimum, it can be shown that Buck Weaver was at least initially aware of what became quicksand-like negotiations between the team and the gamblers, but he wasn’t present at the meetings, and his play belied any hint he was “throwing” anything.

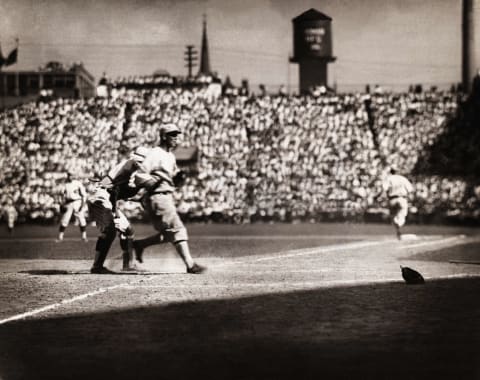

A telling photograph of Weaver’s effort exists. It appeared in the New York Daily News during the Series, and shows Cincinnati’s catcher about to tag Buck out at home. This is a point at which a play can be thrown. The camera froze the moment just before Weaver hits the dirt in what will clearly be a fade-away slide. The attitude of Weaver’s blurred figure suggests that he is running hard. Obviously, the play was close, and Weaver was out, but he could have ensured this by taking a straight route to the catcher, who had to tag him. A minimal argument would be that this still photo appears to be of an honestly-made play.

He made no errors in the Series. (By contrast, in his previous World Series in 1917, he had made four. Those were at short, but Weaver had played most of his early career at short. It wasn’t unfamiliar to him. Of course, the 1917 team was not the Black Sox – they won. No one questioned four errors when the errant player was a world champion.) In 1919 Weaver had nine putouts, 18 assists, and five extra-base hits in the eight games played. He got no money from the gamblers.

But Buckie would be caught in the cogs of machinery both legal and uniquely personal to Judge Landis’ mind, and as a professional athlete he was ground into a large meat patty. Although acquitted by a jury in a fairly crooked state trial featuring disappeared player confessions (not including any by Weaver), Buck and the other seven Black Sox were banned for life from baseball by Landis, the newly-minted first commissioner.

That decision followed close upon the heels of their actual acquittal by a jury, and near the heels of Weaver’s .333 effort in 1920. Oddly, a good deal of the language of the fateful, labored sentence that became Landis’ decree about the Black Sox seemed specifically aimed at Weaver (italics): “Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player who throws a ball game, no player that sits in conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways of throwing a game are discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball!” We’ll return to this later.

The Aftermath

As Asinof details with sad eloquence in his history of the Black Sox, Weaver would challenge that language for the rest of his life without success.

In December, 1921, Weaver even met with Landis and laid out his defense. The new commish treated him with surface cordiality, and Buck essentially admitted he knew of suggestions that the Series could be thrown, but argued that he didn’t even know a consensus among the conspirators had been reached to do that, or who, if anyone, was paid. He admitted a discussion with Chick Gandil – but none with any gamblers – about throwing the games. He pleaded that he could have used any money offered as his brother and he had opened a drugstore in 1919, but he felt that he couldn’t go through with playing dishonestly, and he didn’t. He felt his play proved his innocence on a very gray playing field. Finally, his teammates were his friends – hence, his silence about the supposed conspiracy.

That last point was probably the weakest argument to Landis, who objected that, knowing what Weaver knew, he should have gone to management and reported the other seven Black Sox. Period. The stance calls to mind Senator Joe McCarthy, decades before its time. Landis did say he would consider the player’s argument, and send him a letter.

In a glaring exposure of his fundamental meanness as a human being, however, Landis never wrote that letter. Instead, he made a pronouncement to the press: “Birds of a feather flock together. Men associating with gamblers and crooks should expect no leniency.”

Such a bird could not expect, either, the chief regulatory officer in his industry would be as good as his word – even if only in a matter of common courtesy. And never mind the shakily-founded suggestion of Weaver’s personal contact with “gamblers and crooks.”

Three years later Weaver finally forced his penurious owner, Charles Comiskey, to pay him wages owed by contract, but not paid because he wasn’t playing. This was an out-of-court settlement, and the technically innocent Weaver tried Landis again. This time Landis reinforced that forever means forever when it came to Black Sox, and that, perhaps, he viewed Weaver’s argument as something to be toyed with. Rather meanly, and with little consideration of the record, Landis argued that at trial (“from the witness stand”) Weaver did not refute the gambler “Sleepy” Bill Burns’ account of a meeting with him and other co-conspirators. Weaver had never been on the stand during the state trial, and had been denied specific requests to testify and for a separate trial.

Future commissioners Happy Chandler and Ford Frick also denied appeals by Weaver, who lived out his enforced retirement at his drugstore, except for a brief foray in 1927 into semi-pro ball, using his own name, unlike some of the rest of the Black Sox. At the age of 37 Buckie heard a few more cheers on inferior Chicago-area playing fields, playing a game he loved. Mostly, though, he played cards, and sometimes went to the horse track. He didn’t drink.

A Film and Historical Perspective

Director John Sayles’ brilliant transfer of Asinof’s Eight Men Out to the big screen is a film more about Weaver than the book on which it is based. Where the film succeeds is in the life-like characterization of several of the players. John Cusack, who looks considerably younger and more innocent than the circa 1919 photos of Weaver, has the third baseman’s part. At one point he sits quietly on a stoop with neighborhood children, talking about his love for the game. This is a tremendously effective scene for true fans and players. Buckie talks of putting a perfect swing on a pitch and feeling the ball “give.”

“Damn,” he says, “if you don’t feel like you’ll live forever.” The facts suggest strongly that Sayles has gotten Weaver right.

However, Judge Landis might also be cut some slack in regard to the Black Sox as well from the “distance” of 98 years. As SABR.org notes, “there was a method to Landis’s harshness. By making an example of Weaver, Landis sent a message to the rest of Organized Baseball that any player who learned of a fix was guilty in the eyes of baseball unless he immediately reported it.”

More from Call to the Pen

- Philadelphia Phillies, ready for a stretch run, bomb St. Louis Cardinals

- Philadelphia Phillies: The 4 players on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore

- Boston Red Sox fans should be upset over Mookie Betts’ comment

- Analyzing the Boston Red Sox trade for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen

- 2023 MLB postseason likely to have a strange look without Yankees, Red Sox, Cardinals

And this worked. Three players identified by SABR.org on Weaver’s page alone were turned in by opponents and suspended for life within four years of the Black Sox trial for attempted tampering with contracts or bribery to throw a game.

George “Buck” Weaver died of natural causes at the age of 66, walking on Chicago’s South Side to his tax accountant’s office. He didn’t live forever, and professionally, he was murdered young by an inferior jurist who couldn’t sort out the good guys from the bad or didn’t care to because he saw a solution to the problem of gamblers’ influence on MLB.

In retrospect, there seems no reason Landis couldn’t have cut Buck Weaver a break, and use that action to highlight a zero-tolerance policy about contact with gamblers, moving forward from 1920.

Buck Weaver booked a .272 lifetime batting, and defensively was at the Hall of Fame level after a bumpy start to his career. His final three seasons he hit .300, .296, and .333. He was an improving veteran in 1920. He always had been focused on that improvement, beginning with learning to switch hit after his first year in the big leagues, thereby raising his average. He was committed to the game, and he was not really one of the Black Sox.

Next. White Sox 2019 top 10 prospects. dark

But Judge Landis didn’t recognize the gray areas in life. Period.

Buck Weaver played his last big league game at the age of 30.