MLB History: The best major leaguers to come out of Cuba

As the major leagues formulate a new method of bringing that nation’s stars here, a look back at the greatest players in MLB history to come out of Cuba.

More than 200 Cuban-born players have appeared in MLB history. If that number seems high, consider that the major leagues have operated for more than 140 seasons, and that Cubans have been playing for most of that time. On average, that means only about two Cubans per season have appeared on major league rosters.

That will certainly change profoundly with finalization of an agreement between MLB and Cuba making it far easier for Cuban natives to join big league rosters. Such players will no longer be required to have fled their homeland as refugees, often employing dangerous methods, as has been the case for many years.

Cuba has long been a baseball hotbed, producing first-magnitude stars. The first Cuban of note to make a big league roster was Armando Marsans, from Matanzas, who played for the Cincinnati Reds and several other teams from 1911 through 1918.

Ironically, Marsans came to the United States in 1898 as a refugee – of the Spanish American War. He was 11 at the time. He returned to his homeland as a teen where he was a star for a team that happened to play the Reds in a spring exhibition in 1908. The Reds were suitably impressed.

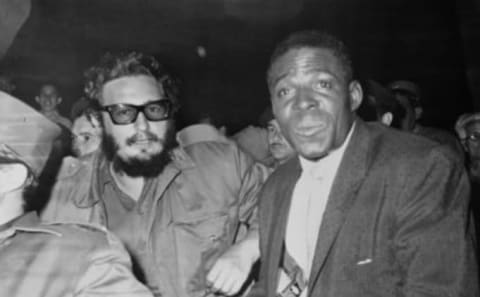

Probably the peak moment for Cuban involvement in the major leagues was the 1960s when –often in the wake of the Castro takeover of that island — players of the stripe of Tony Oliva, Bert Campaneris, Tony Perez, Mike Cuellar and Luis Tiant emigrated in search of better opportunities. Castro may have been a big fan of baseball, but he was not a big fan of his country’s best ballplayers leaving their home fields behind.

In recent years, too, talent has found its way from Cuba to the U.S. In the 1980s and 1990s, Jose Canseco and Rafael Palmeiro made their names. Today, stars of the magnitude of Jose Abreu, Aroldis Chapman, Yasiel Puig and Yoenis Cespedes perform.

Who are the 20 best players to have come from Cuba? This presentation ranks them based on their career Wins Above Replacement value. It’s a diverse list, ranging across more than a century of the game’s history. It includes seven pitchers and 13 position players. The only requirement for inclusion is that the player must have been born in Cuba. For each player, his hometown, the teams he played for, major league seasons and career WAR are shown.

You may detect one inherent bias…against present-day players. That’s due to our use of career WAR as the ranking stat, a decision that harms players whose careers have not yet concluded. As an example, that’s one reason Yasmani Grandal (+13.5 career WAR) is not (yet) included. He may make it someday.

20. Aroldis Chapman, Holguin, Reds, Yankees, Cubs, Yankees, 2010-Present, +16.0

Chapman is the quintessential modern reliever, a 100-mph left-hander. Between 2012 and 2016, he annually chalked up at least 33 saves, and he has 236 for his career.

Chapman’s work during the 2016 World Series – notably his seven and two-thirds World Series innings – is credited in large part with the Cubs’ ability to rebound from 3-1 deficit to defeat the Cleveland Indians. That’s true even though Chapman gave up the eighth inning, game-tying home run to Rajai Davis.

Still his best season was probably 2012 when, pitching for the Reds, he appeared in 68 games, compiled a 1.51 ERA and saved a career-high 38 games as Cincinnati made a final post-season appearance.

Traded to the Yankees prior to the 2016 season and then to the Cubs midway through that season, Chapman signed a five-year, $6 million deal with the Yanks as a free agent following the 2016 World Series. Since then he has appeared in 85 games, saving 54 of them in 102 innings of work.

Before coming to the U.S., Chapman pitched four seasons for his home town Holguin team in the Cuban professional league. Since coming to the big leagues, he has pitched strictly in relief, appearing in 490 games. His nickname reflects both his abilities and his heritage. Chapman is familiarly known as “The Cuban Missile.”

19. Jose Abreu, Cienfuegos, White Sox, 2014-Present, +18.7

Abreu began playing as a 16-year-old for his native Cienfuegos club, and over a decade averaged .341 with 178 home runs before defecting. Three times he topped 30 home runs, twice averaging more than an RBI per game. In each of his final five seasons in Cuba, he compiled an OPS in excess of 1.000, topping at an extraordinary 1.583 during the 2011-12 season.

Abreu’s star status complicated his ability to sign with a U.S. team. Eventually, he resorted to the use of agents — functional kidnappers – who spirited him out of the country and stashed him at a hideout in Latin America until arrangements could be made with an American team. That team turned out to be the White Sox.

Since signing, he has performed at the same level he did in Cuba. He was Rookie of the Year in 2014 when he batted .317 with 36 homers. He became an All Star that season and returned to the mid-summer Classic in 2018.

Through his first five seasons in Chicago, Abreu has hit 146 home runs, driven in 488 runs and averaged .295. His relatively modest 2018, 22 homers, 78 RBIs and a .265 average, was the worst since he was a 17-year-old in Cienfuegos.

The decade Abreu spent in Cienfuegos crimps Abreu’s position on lists such as this one by limiting his ability to build up truly imposing career numbers. So consider his big league averages: 171 hits, 29.2 homers, 97.6 RBIs, and the aforementioned .295 batting average.

He is committed to the White Sox for the next two seasons. Entering his age 32 season, the question going forward will be whether Abreu’s 2018 decline represents an aberration or the accumulation of aging.

18. Jose Cardenal, Matanzas, Giants, Angels, Indians, Cardinals, Brewers, Cubs, Phillies, Mets, Royals, 1963-1980, +20.7

Cardenal came to the U.S. as a child, signed with the Giants as a 16-year-old late in 1960, but truly blossomed following his 1964 trade to the Angels. In Anaheim, Cardenal for the first time established himself as a regular, batting .250 with 11 home runs in 1965.

In an age when individualism was only beginning to be grudgingly accepted on the field, Cardenal’s showy approach to the game – he famously labeled himself “No. 1 hotdog” – probably contributed to the fact that he relocated every year or two.

Landing in Chicago at the start of the 1972 season, Cardenal became a celebrity, if not a true star. He batted a career-best .291 with a career-best 17 home runs. One year later he hit .303 with 11 home runs. Through 1977, the ever-cheery Cardenal became at least an attitudinal successor to Ernie Banks, his production topping at .317 in 1975.

But after Cardenal’s average tailed to .239 in 1977, the Cubs traded him to the Phillies, where his wandering through the majors resumed. He left Philly for the Mets in mid-season 1979, and played briefly for the Royals in 1980 prior to his retirement.

Never a front-line star nationally, Cardenal’s career peaked in Chicago, where he drew nominal MVP support in both 1972 and 1973. Although he modeled the uniforms of nine different teams, nearly half his career WAR with the Cubs.

17. Yoenis Cespedes, Campechuela, Athletics, Red Sox, Tigers, Mets, 2012-Present, +21.8

Cespedes signed with Granma of the Cuban National Series as a 17-year old prior to the 2003-04 season. He was an immediate sensation, following his .302 debut with .313 and .351 averages while still a teen-ager.

For Granma, he hit 169 home runs and drove in 553 runs across eight seasons prior to choosing the dangerous path of defection and signing with the Athletics at age 26.

In Oakland, Cespedes’ power game showed itself to be legitimate. He hit 23 in his 2012 major league debut and 26 in 2013. But when the A’s sought pitching help to fortify their 2014 post-season run, they stunned baseball by trading Cespedes to Boston in July of 2014 for Red Sox ace Jon Lester.

In Boston, for the first time in his career, Cepedes foundered, prompting the Red Sox to trade him to Detroit at season’s end. The Tigers moved him to the contending Mets the following mid-season, and the old Cespedes emerged in the New York limelight. He batted .287 with 17 home runs in 57 games as the Mets reached the World Series.

In that Series, Cespedes’ plate struggles contributed to New York’s defeat in five games to Kansas City. He batted just .150 in 21 plate appearances.

Since then, Cespedes has been hampered by a series of leg injuries. They limited him to just 321 plate appearances in 2017 and to just 157 in 2018. His ability to return to full form is considered central to New York’s ability to contend in 2019.

16. Orlando Hernandez, Villa Clara, Yankees, White Sox, Diamondbacks, Mets, 1998-2007, +23.2

Orlando is the half brother of Livan and his senior by a decade. The fact that Livan preceded him to the majors has everything to do with politics, initiative and opportunity, and nothing to do with talent.

Orlando began pitching for the Havana Industriales in the early 1990s, but he was not an immediate success. Between 1992-93 and 1994-95, however, he compiled a 36-6 record. His participation in the 1992 Olympics and the emergence of his already-exiled younger brother brought awareness of the pitcher — by then known as El Duque — to Latin scouts.

But a criminal case in which he was involved complicated his nation’s inevitable reticence to allow him to emigrate, forcing Hernandez to surreptitiously defect late in 1997. Safely out of Cuban hands, he signed with the Yankees, proved himself during a brief minor league stint, and by 1998 was a 21-game starter on one of the best teams of all-time, that season’s 114-win World Series champions. Hernandez went 12-4 for that team, winning one game in the ALCS and another in the World Series.

Hernandez went 29-22 as the Yanks repeated in 1999 and 2000 before age began to take its toll. He was 35 in 2001, managing just a 4-7 record in 16 starts. He sat out all of 2003 with an arm injury, and following a lackluster 2004 was signed as a free agent by the White Sox.

On a Chicago team destined for its first World Series since 1959, Hernandez played a supporting role. He made 22 starts, compiled a 9-9 record over 128 innings. The pitching-dominant Sox used Hernandez sparingly in the post-season, but he did make two relief appearances, allowing no runs as Chicago swept Houston.

Traded to Arizona following the season, Hernandez made a handful of appearances before being traded to the Mets in May. He was 40 at the time. Even so, he made 44 starts for the Mets before retiring at 41 in 2007.

15. Tony Taylor, Central Alava, Cubs, Phillies, Tigers, Phillies, 1958-1976, +23.4

Taylor turned pro as an 18-year-old, played independent ball in Texas and Cuba before being drafted by the Giants organization. A second baseman, he split time between the American minors and the Cuban winter league until being drafted by the Cubs in 1957. Paired with shortstop Ernie Banks, Taylor became a regular, serving as the club’s leadoff hitter.

Early in 1960, however, the Cubs traded Taylor to Philadelphia for pitcher Don Cardwell, who immediately ingratiated himself to the North Side with a debut no-hitter. In Philly, Taylor suffered through the ignominy of a 1961 season in which the Phils lost 23 consecutive games and finished last.

Taylor was never a power hitter; his career high in home runs was 9, that coming in 1970. His forte was defense combined with just enough offense – he was a career .260 batter – to reflect the 1960s standard.

His best season was probably 1963, when he hit. 281 and drove in 49 runs. Between 1960 and 1970, Taylor was as close to a positional; fixture as the game knew, starting 80 percent of his team’s games, almost all of them at second. Only 24 when he arrived in Philadelphia, he was 35 when the Phils traded him to Detroit in 1971. With the Tigers, he made his first and only post-season appearance, batting .133 in a four-game ALCS loss to the Oakland Athletics.

Released in 1973, he signed as a free agent back in Philadelphia, and was released again following the 1976 season.

14. Livan Hernandez, Villa Clara, Marlins, Giants, Expos/Nationals, Diamondbacks, Twins, Rockies, Mets, Nationals, Braves, Brewers, 1996-2012, +25.0

Although a decade younger than his half-brother, Livan Hernandez lived apart from the rest of his family, and early on grew disgruntled with what he viewed as his lot in life. Establishing himself through a handful of teen-aged seasons in the Cuban National Series, Livan jumped during a 1995 visit to Mexico, signing with the Florida Marlins. Following one minor league season, he hit the majors in 1997, winning nine of his 17 starts with a 3.18 ERA.

The 1997 post-season truly made Livan’s reputation. He was named Most Valuable player of both the NLCS and the World Series, starting three games and pitching more than 24 innings. In those 24 innings – and, some alleged, with a substantial assist from generous plate umpire Eric Gregg – Hernandez struck out 23 opponents. He was barely 22, and he was a star.

When the Marlins tore apart their championship roster in 198, Hernandez survived – for a time. By mid-season 1999, though, he was gone, too, traded to San Francisco for two prospects. He lasted three and one-half seasons, compiling a 45-45 record.

From there, Hernandez’ major league adventure became an extended odyssey. The Giants traded him to the Expos, who –after morphing into the Nationals – traded him to the Diamondbacks. The Twins signed him as a free agent prior to the 2008 season, but waived him in August and he was picked up by the Rockies. For the next three seasons, he signed on as a hired pitching gun with anybody who would have him until they kicked him out.

His career 178-177 record and 4.44 ERA were compiled in 519 innings encompassing more than 3,000 innings; Hernandez was nothing if not a workhorse. He retired in 2012 at age 37.

13. Tony Gonzalez, Central Cunaga, Reds, Phillies, Padres, Braves, Angels, 1960-1971, +27.0

Gonzalez was 17 when he signed with the Havana Sugar Kings in 1954. At the time the club maintained a close working relationship with the Cincinnati Reds, and that relationship led to Gonzalez’ signing for a bonus the player later estimated at $10.

With Cincinnati’s Havana-situated International League team, Gonzalez batted .300 in 1959, hitting 20 home runs and earning a major league promotion. At that season’s trading deadline, though, the Reds sent him and Lee Walls to Philadelphia for Wally Post and a couple of prospects.

The deal proved a coup for the Phillies when Gonzalez batted .299. He hit .302 in 1962, .306 in 1963 and got MVP support. Gonzalez was a centerpiece of the Phils’ 1964 lineup that made a run at the NL pennant before collapsing. He remained with the Phillies through 1968 when, approaching his age 32 season, they made him available in the 1969 expansion draft.

San Diego took him, but used Gonzalez mostly as a bargaining chip, shipping him to Atlanta that summer as the Braves sought to boost their pennant prospects. With the Braves, Gonzalez batted .294 in 89 games, helping them to the NL West championship and a spot in the initial NLCS against the Miracle Mets. Atlanta lost in three straight despite Gonzalez’ .357 average with a home run.

Sold to the Angels prior to the`1970 season, Gonzalez played two more years before being released.

12. Yunel Escobar, Havana, Braves, Blue Jays, Rays, Nationals, Angels, 2007-2017, +27.1

Escobar was a 20-year-old in his fourth season playing for the Industriales of his Havana home town when the Braves drafted him. Making his way to the United States, he interned for three seasons in the Braves system before making the majors for good in 2007.

Escobar batted .326 that rookie season and established himself as the club’s regular shortstop. Still in July of 2010 the Braves traded him to Toronto, which saw Escobar as the successor to the team’s aging shortstop, Alex Gonzalez.

Escobar measured up, hitting .340 during what was left of the 2010 season and .290 in 2011. But when his production fell off in 2012, Toronto included him in a 12-player deal with the Marlins, who a month later forwarded him to the Rays.

In Tampa, Escobar became Joe Maddon’s regular shortstop. His only post-season appearance came in 2013 when he batted .467 during a losing division series matchup against the Red Sox. But when Tampa’s fortune’s flagged, he was traded twice again, this time winding up in Washington by way of Oakland. He played one season for the Nationals, batting .314, but in 2016 was traded a final time, to the Angels. Following the 2017 season, Escobar for the first time became a free agent, but at 34 he went unsigned.

11. Leo Cardenas, Matanzas, Reds, Twins, Angels, Indians, Rangers, 1960-1975, +27.3

Like Tony Gonzalez, Cardenas was a product of the Reds’ unusually close relationship with Cuban ball during the 1950s. Signed as a 17-year-old out of his nation’s semi-pro circuit, he developed in the U.S. minor league system – including one season with the Reds’ Havana Triple A club – before his 1960 debut as a shortstop in Cincinnati.

As a rookie, Cardenas was good enough to force the Reds to trade long-time shortstop Roy McMillan to Milwaukee, making room for Cardenas full-time. The decision paid dividends when the Reds reached the 1961 World Series, Cardenas hitting in the No. 2 spot and batting .308.

He enjoyed nearly a decade as the team’s shortstop fixture, making four All Star teams. In 1966, Cardenas reached his power limit, producing 20 home runs and driving in 81 runs, both career highs.

Seeking pitching help, the Reds traded Cardenas to Minnesota for Jim Merritt prior to the 1969 season. That gave Cardenas his second and third post-season exposures, Minnesota winning the AL West in 1969 and 1970. Cardenas was a bust in both post-season appearances against the Orioles, batting just .167.

He was 33 when the Twins sent Cardenas to California, spending his declining seasons there, in Cleveland and Texas before being released in 1975. His 16 season career yielded a .257 batting average 118 home runs and that 1961 World Series appearance.

10. Mike Cuellar, Las Villas, Reds, Cardinals, Astros, Orioles, Angels, 1959-1977, +29.4

A late bloomer, Cuellar actually got his start as a teen-aged soldier in the Cuban army, which allowed him to pitch for its team on weekends. Released from service in 1956, he played one season in the Cuban winter league before being signed by the Reds in 1957.

He split his time between Havana’s International League club and winter ball in Cuba until making a brief, unsuccessful, big league debut in 1959. Four minor league seasons and several trades later, he found himself back in the majors pitching for the recently created Houston Astros in 1965. Cuellar was 28 by then and only beginning to develop as a reliable pitcher.

In three full seasons with Houston, Cuellar made 84 starts, compiling a 38-32 record, all the more noteworthy because the Astros never won more than 72 games. When the Baltimore Orioles offered regular outfielder Curt Blefary in exchange for Cuellar, the Astros jumped.

That trade initiated Cuellar’s ascent to stardom. Between 1969 and 1971, Cuellar averaged 39 starts and more than 290 innings, winning 67 games against just 28 defeats. With a mound staff combining Cuellar, Jim Palmer and Dave McNally, the Orioles, of course, won three straight American League pennants. In 1969, Cuellar won the Cy Young Award for his 23-11 season and 2.38 ERA.

Cuellar made two starts in the fated 1969 World Series against the Mets, claiming Baltimore’s only victory and delivering seven strong innings in a fourth game no decision that went to the Mets in 10. He and the Orioles redeemed themselves in 1970, Cuellar’s two starts against the National League champion Reds including the fifth game clincher, a 9-3 win.

He had less success in 1971, losing twice to Pittsburgh during a seven-game series won by the Pirates.

Across seven seasons as a mainstay of the Orioles rotation, Cuellar compiled a 133-88 record. Released at the conclusion of the 1976 season, he signed with California but made just two appearances before retiring at age 40.

9. Camilo Pascual, Havana, Senators/Twins, Senators, Reds, Dodgers, Indians, 1954-1971, +37.5

Starting with neighborhood teams in Havana, Pascual signed to play in the Cuban winter league as a teen in the early 1950s, where the roster included future major league teammate Pedro Ramos. His experience included double duty playing independent ball in the American minor league system, leading to his signing with Washington in 1952.

Though still active in the Cuban winter leagues, Pascual debuted with the Senators in 1954 – beating Ramos there by one year – but going just 4-7 in 48 appearances. All but four of them were in relief. Slowly but inevitably, he distinguished himself. By 1959, he made 30 starts and won 17 of 27 decisions, a record made even more noteworthy by his team’s customary eighth place finish.

When the Senators relocated to Minneapolis-St. Paul following the 1960 season, Pascual went along as the club’s recognized ace. He won 20 games in 1962, 21 more in 1963, and went 9-3 in 1965 as the Twins won the franchise’s first pennant in more than three decades.

Along the way Pascual was named to five American League All Star teams.

Durability was his calling card; he led the American League in complete games three times, pitching more than 240 innings annually between 1961 and 1964 For his career Pascual amassed nearly 3,000 innings of work.

When Twins fortunes hit a brief decline in 1966, Pascual was traded back to Washington, where he found himself with a second-generation losing Senators team. He compiled winning records there in both 1967 and 1968 before being sold to Cincinnati early in the 1969 season.

Released following five inauspicious appearances, the 35-year-old Pascual made brief stops with the Dodgers and Indians before being released in 1971. His showed a career 174-170 record and 3.63 ERA.

8. Jose Canseco, Havana, Athletics, Rangers, Red Sox, Athletics, Blue Jays, Devil Rays, Yankees, White Sox, 1985-2001, +42.5

Cuba may have produced better ballplayers, but it’s impossible to conceive that the island ever produced a more compelling figure than Canseco, the celebrity slugger.

A teen phenom whose twin brother, Ozzie, enjoyed a brief major league career, Canseco’s success was spurred by two pieces of fortune. The first was his father’s ability to secure an emigration visa for his family, which relocated from Havana to south Florida. The second was the happenstance of Jose’s joining a local team whose players included the son of Camilo Pascual. Recognizing talent when he saw it, Pascual tipped the Athletics, for whom he was scouting, and Oakland drafted Jose in 1982.

It didn’t take Canseco long to hit the big time. Following two and a fraction minor league seasons, he hit .302 as a rookie, rattled 33 home runs in 1986, then in 1987 teamed with rookie Mark McGwire to become the “Bash Brothers.” They combined to hit 80 home runs and drive in 231 runs as the A’s finished 81-81, the franchise’s first trip over .500 since 1980.

One season later, the A’s won their first of three straight American League pennants. Canseco produced a league-leading 42 home runs and 124 RBIs in 1988, adding another 54 homers and 158 RBIs in 1989-90. When the A’s beat the Giants to win the 1989 World Series, Canseco batted .357.

Canseco’s celebrity status grew along with his performance, but by the early 1990s rumors of steroid use – later confirmed by Canseco – undermined his value. Despite leading the AL West in 1992, the A’s traded their star outfielder to divisional rival Texas, where Canseco became something of a caricature of himself. He hit 31 home runs in 1994, but by then had gained infamy for allowing a fly ball to bounce off his head over the right field fence in Cleveland for a home run.

With the end of the player strike in 1995, Canseco’s career wandered. He signed as a free agent with the Red Sox, was traded to Oakland inside of two seasons, signed again as a free agent with Tampa Bay, and in 2000 was waived to the Yankees. Between 1996 and 2001, he played with a half dozen teams, each hoping they could revive the late 1980s Oakland Canseco. In the midst of the gathering storm that became the steroid crisis, it never happened and Canseco’s 2001 release by the White Sox was his final one.

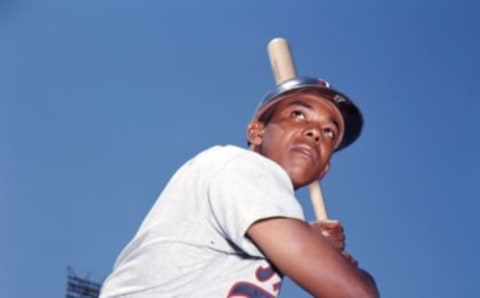

7. Tony Oliva, Pinar del Rio, Twins, 1962-1976, +43.1

As a youth, Oliva’s baseball talent enabled him to escape his otherwise pre-destined life in his native area’s tobacco fields. Starring with a neighborhood team, he was scouted and signed late in 1959 just before the gathering Castro-U.S. tensions would further complicate hopes of emigration.

His first minor league exposure established beyond question that the Twins had a future star. He hit .438 at Wytheville in the Class D Appalachian League, .350 at Class A Charlotte in 1962, and .304 at Class AAA Dallas-Fort Worth in 1963.

As a rookie in 1964, Oliva made an immediate splash. He led the American League in runs, hits, doubles and total bases while winning the batting title at .323. Naturally he was the League’s Rookie of the Year. He also made the first of his eight All Star teams and finished fourth in the Most Valuable Player voting.

In 1965, he proved that his rookie year was no fluke. His .321 average resulted in a second consecutive batting title, and helped the Twins win the American League pennant. In the World Series against Los Angeles, the combination of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale stifled Oliva, who hit just .192 as the Twins lost in seven games.

Oliva was a lifetime Twin, completing a 15-season career in 1976 when chronically bad knees sidelined him. He retired in 1976 when chronically bad knees sidelined him. He retired with 220 home runs, a .304 average and 947 RBIs. To this day, when armchair experts debate the most significant Hall of Fame slights, Oliva’s name is among the first to be raised.

6. Dolf Luque, Havana, Braves, Reds, Dodgers, Giants, 1914-1935, +43.4

The Godfather of Cuban baseball, Luque emerged from a stint in the Cuban army and brief time with local teams to win the eye of a Boston Braves scout. A light-skinned Latin in an age when darker skin would have disqualified him for big league consideration, he signed but made only brief appearances before kicking around the minor leagues.

In 1918 the Cincinnati Reds signed Luque and watched him eventually blossom into a star. He went 10-3 for the 1919 World Series champions, lost 23 games in 1923, but rebounded to win 27 games in 37 starts in 1924.

Across 20 seasons, Luque made 367 starts and pitched 3,220 innings with a 194-179 record.

In retirement, Luque returned to his homeland, where his big league fame made him a celebrity. He had regularly returned to pitch in the Cuban Winter League. His retirement and advancing age did not diminish that; into his 50s, Luque continued mound duties in his homeland. He managed Almanderas to a succession of championships, finishing first or second 14 times in 19 seasons. In his later years, Luque influenced the careers of several prominent Cuban players who emerged in the 1950s.

His death, of a heart attack in 1957, was an occasion for national mourning.

5. Minnie Minoso, Havana, Indians, White Sox, Indians, White Sox, Cardinals, Senators, White Sox, 1949-1964, 1976, 1980, +50.5

Saturnino Orestes Minoso took a circuitous path to the majors that began in the sugar cane fields of the 1940s, wound through semi-pro ball, and eventually took him to stardom in the Cuban winter league.

The first American to discover his talent was Abe Saperstein, famed as founder of the Harlem Globetrotters, but segregation remained the policy in the majors so Minoso signed instead with the Negro League’s New York Cubans.

In 1948, Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck signed Minoso and farmed him to Dayton. Following a brief appearance with the Indians in 1949, Minoso lingered two more seasons with San Diego of the Pacific Coast League before cracking the majors for good in 1951.

Less than a month into his big league career, the Indians packaged Minoso to Chicago in a three-team, eight player trade. The White Sox installed the 25-year-old in left field and he burst into stardom, batting .324 with 10 homers, 74 RBIs and a league-leading 31 stolen bases. Minoso finished second in Rookie of the Year voting, fourth in Most Valuable Player voting, and made the first of an eventual seven All Star teams.

As sharp as was Minoso’s debut, he soon improved. He hit .303 in 1953, .320 in 1954, topped 100 RBIs in both seasons, and led the American League in steals for three consecutive seasons. Combining power with speed, he hit 18 triples and 19 home runs in 1954. His naturally bubbly personality brought him popularity on the South Side even as his game brought him fame.

So it came as somewhat of a shock when the White Sox traded their star back to Cleveland in 1958. In his departure, Minoso would fuel the path to Chicago’s 1959 pennant, the team’s first in 40 seasons, bringing outfielder Al Smith and pitcher Early Wynn in return. Both would be fixtures in the White Sox’ championship run.

In Cleveland, Minoso topped .300 in 1958 and 1959, then was traded back to Chicago prior to the 1960 season. Minoso hit .311 in his return, making his seventh All Star team and winning a Gold Glove. But he was 34 by then and age-related decline had set in. Following the 1961 season, the Sox traded Minoso again, this time to St. Louis.

He returned briefly to Chicago in 1964 before retiring, only to make two encores. In 1976 and again in 1980, Minoso – in his 50s both seasons – signed for brief stints with the Sox that made him the only player ever to compete in five decades. At age 54 in 1980, he made two unsuccessful pinch hitting appearances.

4. Bert Campaneris, Pueblo Nuevo, Athletics, Rangers, Angels, 1964-1983, +53.1

A member of Cuba’s 1961 PanAm Games team, Campaneris caught the attention of an Athletics scout, who signed him. The young infielder had motivation to succeed; his signing came just says before tensions in the wake of the recent Bay of Pigs invasion dried up emigration avenues, and Campaneris was given 60 days to succeed or be released.

The A’s were woeful in 1964, making it easier for Campaneris to earn his promotion to the major league club. He quickly showed his best asset, his speed, stealing a league-leading 51 bases in 1965, and leading the league for four consecutive seasons.

As the A’s improved, Campaneris’ value grew. He was a mainstay and leadoff man of the team that won three straight World Series between 1972 and 1974, although by modern standards his credentials in that role – on base averages around .300 – are modest. He was viewed as consistent, reliable infielder.

His best World Series was 1974 when Campaneris batted .353 in a five-game victory over the Dodgers.

Still, when Charles Finley broke up the A’s in anticipation of the approach of the free agent era, Campaneris was among the first to go. Released following the 1976 season, he signed as a free agent with Texas, where he made the 1977 All Star team at age 35 before being relegated to part-time duty.

The Rangers traded Campaneris to Texas in 1979. He filled in there before a brief stint with the Yankees in 1983. For his 19 seasons, Campaneris batted an inconspicuous .259, but stole a pitcher-rattling 649 bases.

3. Tony Perez, Camaguey, Reds, Expos, Red Sox, Phillies, Reds, +54.0

As a teen-ager, Perez signed his first professional deal with his hometown Havana Sugar Kings of the International League. The Sugar Kings were a Cincinnati farm team at the time, but that relationship grew more tenuous with the rise of Fidel Castro and its implications for U.S.-Cuba relations.

Perez emigrated in 1960, basically at the last possible moment, touring the Reds minor league system until winning a promotion at the end of the 1964 season. His 34 homer, 107 RBI 1964 season in San Diego had more than a little to do with his elevation.

In 1965, Perez established himself as a middle of the order fixture. By 1967 he produced 26 home runs and 102 RBIs, making his first of seven All Star teams.

The question became where to play him. Initially, Perez established himself at third base, playing there most of the 1967 through 1971 seasons. From the start, however, he split time at first base, and by 1972 he was a regular there.

In 1970, when the Reds won the National League pennant, Perez for the first time hit 40 homers, posting a personal best 129 RBIs with a .317 average. As “The Big Red Machine,” Cincinnati won back-to-back World Series in 1975-76, and Perez played a key role, averaging 20 homers and 100 RBIs.

But free agency arrived following the 1976 season, and the Reds – fearful of getting nothing in return for their slugger – traded him to Montreal. He played three seasons with the Expos, then three more with the Expos and one with the Phillies before returning to Cincinnati as a 42-year-old in 1984.

Retiring with 379 home runs, Perez was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2000.

2. Luis Tiant, Mariano, Indians, Twins, Red Sox, Yankees, Pirates, Angels, 1964-1982, +66.1

The son of a famed Cuban pitcher, Tiant signed with Mexico City of the Class AA Mexican League as a 19-year-old in 1960. In four minor league seasons he went 38-25 before being promoted to Cleveland.

Tiant split time in 1964, but won 10 of his 16 starts with the Indians before establishing himself full-time a year later. He emerged into stardom in 1968, his 21-9 record coming in 32 starts for a team that rose to third in the 10-team AL. One year later, though,, the Indians collapsed and Tiant fell back with his team, going 9-20.

The result appeared to relegate Tiant to fill-in status, and he spent two seasons doing nothing much with the Twins, Braves and eventually the Red Sox, who had taken him on as a free agent. In 1972, though, his always eccentric delivery – laced with gestures, hitches and looks off-target – synched up. In 43 appearances, 19 of them starts, Tiant pitched 179 innings and produced a league-leading 1.91 ERA with a 15-6 record.

It was the beginning of the best seasons of Tiant’s already lengthy career. He won 20 games in 1973, 22 in 1974, and in 1975 was the ace of Boston’s pennant-winning staff. Tiant started three games in that World Series against the Reds, winning the first and fourth games and taking a no-decision in the famed 12-inning Carlton Fisk sixth game.

Granted free agency following the 1978 season, Tiant was 38 when he signed with the Yankees in 1979. He pitched four more seasons, retiring with a 3.30 career ERA and 229 victories over nearly 3,500 innings.

1. Rafael Palmeiro, Havana, Cubs, Rangers, Orioles, Rangers, Orioles, 1986-2005, +71.9

Palmeiro is recalled today for the steroid-fueled suspicions that surround his career. The raw numbers stand out: 3,020 hits, 569 home runs and a .288 batting average. Between 1995 and 2003, Palmeiro never produced fewer than 35 home runs or 100 RBIs. He combined a .371 on base average with a .515 slugging average.

More from Call to the Pen

- Philadelphia Phillies, ready for a stretch run, bomb St. Louis Cardinals

- Philadelphia Phillies: The 4 players on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore

- Boston Red Sox fans should be upset over Mookie Betts’ comment

- Analyzing the Boston Red Sox trade for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen

- 2023 MLB postseason likely to have a strange look without Yankees, Red Sox, Cardinals

A native of Cuba, Palmeiro came to the United States with his family as a child refugee, emerging as a high school star in Miami. The Cubs drafted him in 1985 and brought him to the majors a year later, initially as an outfielder. But when Palmeiro proved his glove was better-suited at first base, Chicago – which already had Mark Grace established at that position — traded him to Texas for reliever Mitch Williams.

It was one of those short-term vs. long-term deals that experts love to analyze. Wiiliams played a key role in Chicago’s rise to the 1989 National League East division title. But Palmeiro became a star in Texas, batting .319 in 1990, .322 in 1991 and improving his power stats annually.

Palmeiro signed with Baltimore as a free agent following the 1993 season, signed back with Texas at the end of 1998, and back with Baltimore at the end of 2003. He was a four-time All Star.

Palmeiro’s Hall of Fame hopes evaporated in 2005. That March he was among players called to testify before a Congressional investigation into the use of steroids in baseball. Palmeiro repeatedly and forcefully denied ever having used them. Later that same season, however, he tested positive for steroid use, becoming the first star to be suspended for that reason.

In retirement, Palmeiro has continued to assert that he never used steroids…at least not deliberately. Even so, his positive test and suspension, appear to have permanently sabotaged his Hall of Fame prospects. In the 2014 election, he was named on just 4.4 percent of ballots, prompting the removal of his name from the candidate list.