MLB Speedsters: Who’s coming? Does it really matter?

The league may be moving away from MLB speedsters, but perhaps it’s because of a lack of other skills around that speed in the modern game.

MLB Speedsters have always been valuable. Ty Cobb and Cool Papa Bell were pretty fast, we’ve been told. Speedy, young Stan Musial was a very useful outfielder who also hit a lot of triples 75 years ago. Joe DiMaggio’s speed, Jackie Robinson’s speed and daring, and the genetically-endowed terrifying speed of Mickey Mantle, Roberto Clemente and Willie Mays were incredibly valuable to their teams.

But all those guys could hit, too.

Herb Washington changed that, and shifted the discussion of speedsters out of the casual, boy-can-he-fly realm, and began the quantified discussion of MLB speed in 1974.

My earliest memory of a quantified MLB player’s speed was a TV announcer declaring Reds outfielder Vada Pinson had run a 9.3-second hundred-yard dash. I’m not entirely sure when I heard that, but for younger folks, the world record for the hundred in yards by Charlie Greene in 1967 was dropped to 9.21 (fully automatic timing), with another runner’s hand-held time of 9.0 in 1974, by which time races were more and more contested at 100 meters (about 109.4 yards).

Pinson was the fast baseball player I ever saw before I was an adult, and I saw Clemente up close, but Washington was something else, we were assured. Among speedsters, Washington was the first true high-level track athlete to cross-over to baseball analogous to Bob Hayes in football. Arguably, however, since Hayes played college football, Washington may be considered the highest profile track athlete to cross over to a major professional sport.

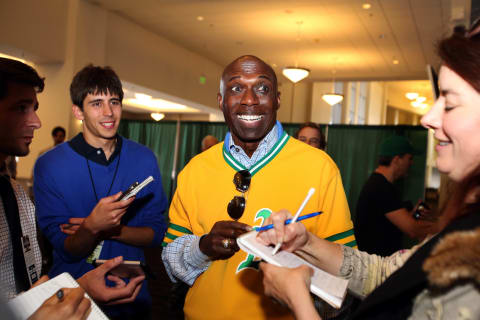

Washington is said to have hit 9.2 for 100 yards in high school, surely a hand-held time, but he also apparently still holds world hand-timed records for both 50 and 60 yards (5.0 and 5.8 seconds) although his times and those race distances are now ancient, discredited history. No matter. Oakland Athletics owner Charlie Finley put him into a uniform with no intention that he would ever hit. He would be a pinch runner, as his ’75 baseball cards indicate with the awkward designation “Pinch Run.” The man would eventually score 33 runs, while stealing 31 bases, without ever holding a bat in major league competition. After parts of two years with the A’s, Washington moved on to the budding professional track circuit.

His career WAR – this is too much – is -0.5 because…who knows? I’d really like to hear that discussion. Who is even one comparison player?

After the Pioneer Who Couldn’t Play

After Washington, other speedsters like Rickey Henderson and Vince Coleman toyed with Maury Wills’ stolen base record, an amazing 104 in 1962, when he did it. Of course, stealing bases – remember when baseball players did that? – is a matter of speed, quickness and perception, that last item involving more than one person sometimes. But that’s getting ahead of ourselves.

After 1987, when Vince Coleman stole 109 bases, the stolen base in MLB baseball began its best imitation of the dodo. After that season, 75 or more bases were stolen only eight times, and four of those totals belong to Coleman and Henderson. No one after ’87 stole more than 93 bases, and Henderson did that in 1988. In the current decade, Dee Gordon’s MLB-leading 62 steals in 2014 is pretty much the gold standard.

Baseball went through its Steroid Era, but of course that doesn’t mean that speedsters weren’t valuable for defensive purposes after ’87.

And that brings us up to 2019 and the MLB Pipeline future top speedsters by team with this observation: 50, 60, or 100-yard or meter times aren’t that important in baseball. We now measure MLB player speed in feet per second, which makes sense since first base is only 90 feet away. See that quickness thing above.

Who Are These Guys?

The speedsters of the future are for the most part fairly anonymous players. They aren’t as well-known as any team’s top minor league slugger. (Think of Rhys Hoskins at Reading in 2016, when he tallied 38 home runs and 116 RBI. Now tell me who the fastest player on Philadelphia’s minor league teams that year was.)

Among the 30 players MLB Pipeline lists on their list of speedsters, six to eight seem fairly close to showing up in MLB parks, perhaps as early as this season.

The National League

In the NL East, only one of the team-leading speed merchants really seems ready for MLB action, Victor Robles, an outfielder with Washington. Robles has actually already played in 34 games over two seasons for the Nationals and has an entirely reasonable slash line of .277/.337/.506. He also has stolen three bases in six attempts. The next closest player in the division is probably Cristian Pache, who will likely start his season with the Double-A Mississippi Braves. However, the very first observation of the Pipeline writers about him is “Pache still hasn’t learned to use his outstanding speed on the basepaths consistently.” He is, despite that, “perhaps the best defensive outfield prospect in baseball.” So that’s one MLB player in the pipeline in the NL East, and one “maybe.” The remaining team-best speedsters in the division are projected to start their seasons at Single-A levels.

Moving to the NL Central, the real possibility for MLB competition is outfielder Cole Tucker of the Pirates. He will likely start the season at Triple-A Indianapolis. Tucker has stolen 82 bases over the past two seasons at the advanced Single-A and Double-A levels with a 75.2 percent success rate, and has posted a .704 minor league OPS thus far. Look for a late-season look-see with the Bucs for him. A “maybe MLB” player in the division could be Cincinnati’s Jose Siri, but Siri’s batting average dropped from .275 at the Single-A level in ’17 to .239 at the Single and Double-A levels in ’18. Thus, he is probably more of a “maybe” than Pache. Once again, the remaining top sprinters in the division as selected by MLB Pipeline are likely Single-A players this coming season, and may never reach the MLB level.

In the NL West a fairly definite MLB prospect is middle infielder Garrett Hampson of the Rockies. Hampson has “double-plus speed,” and has stolen 123 bases in 305 MiLB games in his three-year career with a very promising 84.2 percent success rate. More than that, he has posted a career BA of .315. Hampson will probably take the field this spring with Triple-A Albuquerque, but the rest of the division’s speedsters are probable Single-A players.

The American League

Jumping to the already talent-heavy AL East the best potential MLB player for the near future is probably Roemon Fields, but he is now 28, and he struggled to a .238 BA in ’18 with Triple-A Buffalo in the Blue Jays organization. However, Fields has some truly impressive stolen base totals – 213 for a 75.5 percent success rate, most of those steals coming against Double and Triple-A defenders in the past four years. The drop in BA of 53 points between ’17 and ’18 at the Triple-A levels is concerning, but Fields is also a terrific center fielder. Once again, the rest of the division’s top prospects are going to be Single-A players this summer. Do we see a pattern developing about Pipeline’s fastest prospects? (Younger players are faster.)

In the AL Central no Pipeline player is projected above the Single-A level for this season, but Detroit’s outfielder Derek Hill may be the most promising, despite an impressive history of stints on the seven-day DL. He hit only .239 at the advanced Single-A level last year, but despite a fairly impressive 35 stolen-base total in both ’16 and ’18, he seems destined for that level again this season. Perhaps Hill’s most promise is in his genes. He is the son of Dodgers scout Orsino Hill and the cousin of Darryl Strawberry, and he will be only 23 all season.

Finally, the AL West gives us perhaps two more MLB-ready players, Athletics shortstop Jorge Mateo, who will likely start this season with Triple-A Las Vegas, and Astros outfielder Myles Straw, who is also slated for Triple-A this year, in Round Rock. Both of these players “bring the numbers” thus far.

In Mateo’s case those numbers largely surround his speed – 259 steals in 326 attempts (79.4 percent success) with minor league-leading 82 in ’15. Unfortunately, his ’18 campaign represented a fall-off (.230 BA and 25 steals in 35 attempts). Nonetheless, expect to see Mateo in MLB at some point relatively soon. He is widely considered one of the very fastest players in the minors, and will be 23 until late June.

Straw posted a ridiculous 88.6 percent success rate (70 for 79) in stolen bases and earned an Astros playoff roster spot in ’18. Additionally, he has been a minor league BA leader with a .358 campaign in ’16. His overall MiLB BA over four years is .302, and in nine ABs for the Astros, he had three hits. Straw will be 24 for the entire 2019 season

Last Word

Are there a few players among the vast majority of Single-A players identified as team speedsters by MLB Pipeline who will make it to The Show? Probably. These baseball sprinters have at least one tool prized by major league teams, and probably not enough has been said here about defensive speed.

More from Call to the Pen

- Philadelphia Phillies, ready for a stretch run, bomb St. Louis Cardinals

- Philadelphia Phillies: The 4 players on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore

- Boston Red Sox fans should be upset over Mookie Betts’ comment

- Analyzing the Boston Red Sox trade for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen

- 2023 MLB postseason likely to have a strange look without Yankees, Red Sox, Cardinals

For many of those Single-A burners to make it to baseball’s top level, however, a bit more emphasis on the value of a stolen base will have to emerge. Maybe some analytic wonks will start to study the potential for swiped bags simply because of the number of pitches MLB batters now see. Perhaps some advantage can be perceived in defensive shift situations.

The top runners in professional baseball are no longer among the fastest people on earth as they were 50 or 60 years ago. Vada Pinson probably wouldn’t have been that far behind Bob Hayes in a 60-meter race, but few of baseball’s current speedsters would come within even seven meters of Usain Bolt in his prime at that distance.

That doesn’t really matter, of course, because stealing bases is a matter of experience, reading pitchers, timing pitchers, coaching, and naturally, now, data.

Next. Players avoiding arbitration around MLB. dark

Perhaps the stolen base will resume its former importance sometime soon. See, every MLB team has an analogous MLB speedsters question to this one for the Boston Red Sox: Why has Jackie Bradley Jr. only stolen 47 bases in his career thus far? Go ahead, add up his hits, walks, and HBPs.