White Sox: 8 Misconceptions About The Black Sox Scandal

In the centennial season of the worst scandal in MLB and White Sox history, a SABR research panel recalibrates popular public misimpressions about the Black Sox scandal.

In the entirety of MLB and White Sox history, the 1919 Black Sox scandal remains the biggest and best-known stain on baseball’s reputation.

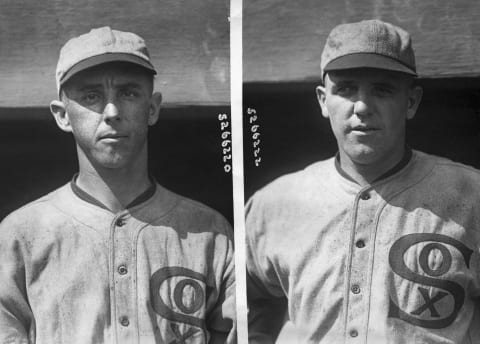

The story of how eight members of the Chicago White Sox – Shoeless Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, Lefty Williams, Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg, Happy Felsch, Buck Weaver and Fred McMullin -conspired with gamblers to fix the 1919 World Series has been detailed in numerous books, both fictional and non-fiction. It has also provided the backdrop for several of the best-known baseball-themed movies of all time, including John Sayles’ 1988 “Eight Men Out” and Phil Alden Robinson’s 1989 “Field of Dreams.”

Over the years, however, several mythologies have grown up around the scandal, many of them perpetuated either by print or in film. Now, researchers specializing in the era and affiliated with the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) have released a new study timed to coincide with the start of the scandal’s centennial season and designed to correct some of the scandal’s most enduring fallacies.

Titled, “Eight Myths Out,” the study can be viewed at the SABR website. The effort was coordinated by Jacob Pomrenke, who chairs the organization’s Black Sox Era committee, and involves work by dozens of researchers, many of whom are published authors of books or papers on the era.

The report is not designed as a comprehensive review of factual errors or misperceptions regarding the scandal, the researchers’ judgment being that would require a more comprehensive study and would engender a morass of debates regarding what truly qualified as a provable myth as opposed to mere suspicion. Rather, they chose to focus on eight of the most incontrovertible misperceptions that also seemed to have gained the strongest foothold in modern media and culture.

Here are the eight myths.

Black Sox Scandal Misconception #1: Charles Comiskey as Scrooge

In popular culture, the players’ motivation for agreeing to throw the Series is often presented as the cheapskate approach that owner Charles Comiskey took to operating the team. The study recalls author Eliot Asinof’s assertion in his groundbreaking 1960s book, “Eight Men Out,” that the White Sox “were the best and were paid as poorly as the worst.”

Several scenes from the Sayles movie deliver the same message. In those scenes, Chick Gandil – the first baseman who organized the fix – uses the idea of a big payday to recruit players who view themselves as underpaid, notably Cicotte, the team’s star pitcher.

In fact, the researchers note, the White Sox had one of the highest payrolls in baseball and most players were paid better than their peers. The study points to newly available organizational contract cards available at the National Baseball Hall of Fame documenting that the White Sox’ $88,461 opening day payroll was more than $11,500 higher than the National League champion Cincinnati Reds.

The SABR study notes that in their numerous interviews, the players involved rarely suggested they were influenced to join the scandal by a sense of aggrievement. “The scandal was much more complex than disgruntled players trying to get back at a big bad boss,” the authors write.

Black Sox Scandal Misconception #2: The Cicotte bonus

In both the Asinof book and the Sayles movie, much is made of Comiskey’s failure to deliver on a promised $10,000 bonus supposedly made to Cicotte if he won 30 games. As presented in media, after the pitcher won his 29th game Comiskey ordered him benched to prevent him from earning the bonus.

The book and movie differ on when this incident occurred, but both agree that it was part of Cicotte’s motivation for agreeing to participate.

There are several problems with this myth. Several White Sox players, among them, fix participant Lefty Williams, did have performance bonuses – in Williams’ case, a $500 bonus for winning 20 games – and those bonuses were paid.

But the biggest misperception is the assertion that Cicotte was benched in order to prevent him from earning the bonus. He wasn’t. In fact, Cicotte made two starts following his 29th victory in 1919. In the first he pitched seven innings and allowed five runs, trailing 5-4. The White Sox scored twice in the bottom of the ninth to win 6-5 for Dickie Kerr. Four days later Cicotte started again. He pitched two innings, faced eight batters and allowed three hits as well as one run. The White Sox eventually lost 10-9.

Beyond that, the SABR study notes, the evidence demonstrates that Gandil and Cicotte were already enmeshed in planning the fix at the time those games were played.

Black Sox Scandal #3: Who started it?

The myth is that the naïve, uneducated ballplayers were conned by the savvier New York gambling element into taking part in the fix. As a result, the perception is, the players quickly found themselves in a situation outside their ability to control. Abe Attell (pictured above), a go-between for Arnold Rothstein who communicated with the players, stated as much in an interview with Asinof late in his life.

The evidence leads to a different conclusion. It points to Gandil and Cicotte as initiators of the fix based on their early conversations with Boston gambler ‘Sport’ Sullivan and Sleepy Bill Burns, a former pitcher linked to gamblers.

While Rothstein did become involved, and doubtless did very well in his Series wagers, the plot originated with the players and spread through other gambling elements before ultimately involving Rothstein’s operation.

The SABR study finds that Gandil built his network of players deliberately and slowly over time, the fix details worked out over the course of several meetings. It describes coordination of the fix as “a total team effort” with the White Sox players themselves “doing much of the heavy lifting.”

As evidence to support that contention, it cites numerous biographical articles on the participants, among them Sullivan, Maharg, and Gandil.

Black Sox Scandal Misconception #4: The myth of the Hitman

One of the most powerful moments of both the Asinof book and the Sayles movie occurs the night before the Series’ eighth and final game. Williams, Chicago’s scheduled pitcher, is confronted by a gang hitman named “Harry F” who threatens the pitcher’s family if he does not lose the next day’s game in the first inning.

In fact, there was no such incident and no hitman. The concept of “Harry F.” was a fiction invented by Asinof and inserted into the book as protection against copyright infringement of his material. Asinof’s publisher suggested the inclusion as a trap in the event someone else used the hitman story in their own work without citing his book.

The SABR study notes that on several occasions prior to his death, Asinof confessed to having manufactured the scene involving Harry F. and Williams. The irony is that so many subsequent authors have done exactly what Asinof feared – unquestioningly adopted the Harry F. narrative as factual – that it has come to be entrenched as part of the broader narrative.

Nor, the study finds, is there much evidence suggesting that Williams was threatened in any way. The only existing report to that effect involves a tale told by a former neighbor of the Williams family who supposedly was told by Mrs. Williams when he was a child of some sort of vague threat.

Black Sox Scandal Misconception #5: The momentary scandal

The myth is that the Black Sox World Series scandal was a one-off, an isolated event.

In fact, it was merely the best known of numerous betting scandals – many proven, a few merely suspected – from that era. Those scandals reflected the linkage between the gambling and sports industries at the time and were a necessary component to the World Series fix.

There have been suspicions, explored most deeply in Sean Devenney’s book, “The Original Curse,” that the 1918 World Series between the Cubs and Red Sox may also have been fixed. In fact, some have suggested that the 1919 White Sox got the idea of a fix from rumors about the 1918 Series.

There has been additional speculation, much of it based on statements by White Sox players, that players continued to fix games during the 1920 season, manipulating game outcomes in order to keep the pennant race close.

The SABR report notes that veteran first baseman Hal Chase “was caught red-handed bribing teammates and opponents alike in 1918, but was whitewashed by the National League.”

It quotes baseball historians Harold and Dorothy Seymour as asserting that the scandal was not an aberration brought about by a handful of villainous players. It was a culmination of corruption and events at corruption that reached back nearly 20 years.”

Black Sox Scandal Misconception #6: The cover-up

The myth is that while there were rumors and suspicions of improper activity during and shortly after the Series, no concrete, actionable evidence surfaced until a grand jury was convened in Chicago late in the 1920 season.

In fact, the SABR researchers document, Comiskey and other members of the game’s ruling group learned of the fix as early as the first game (and possibly even before) but did nothing in the hope that the matter would not come to light and soil baseball’s reputation.

The study notes that Comiskey admitted in 1930 to having heard reports about a fix before any games were even played. It further notes that he hired investigators to explore the rumors that winter, not for the purpose of exposing them but to determine the extent of the event’s threat to the game if it became public.

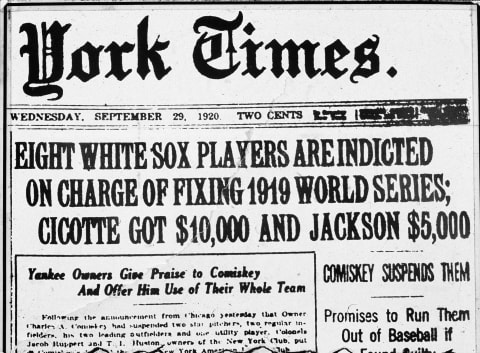

Eventually, of course, it did become public. That was not, however, due to work by baseball officials. Rather it was the work of reporters such as James Cruisenberry and Hugh Fullerton as well as a Chicago-based gambling newspaper called Collyer’s Eye that forced the issue to light. Their work forced prosecutors to convene the grand jury that in September of 1920 coalesced the evidence leading to the players’ indictments and suspensions.

Black Sox Scandal Misconception #7: The myth of the stolen confessions

It is another of the most powerful moments of the 1988 Sayles movie. During the trial, an attorney asked to produce the confessions reportedly signed by Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams reveals that he cannot do so because they cannot be found and apparently have been stolen. The revelation produces gasps of shock.

The scene was apparently intended to depict the corrupt nature of trials in Chicago at the time, and possibly also to raise the idea of complicity between the team’s lawyers and the gamblers in the theft.

The fact is the trial contained no such suspenseful moment; in the film, it was entirely a re-creation for dramatic purpose. While it is true that the confessions were at one point stolen, that fact was discovered well in advance of the trial and stenographers re-drafted the confessions anew from their preserved transcripts.

As a consequence, the theft was at most a minor distraction, known by all parties in advance, easily overcome, and playing no role in the jury’s eventual acquittal of the eight accused players.

By the way, if you are interested in reading the confessions today, they are available for viewing by contacting the Chicago Historical Society, which is the repository for many documents related to the Black Sox.

Black Sox Scandal Misconception #8: The myth of the players’ silence

Asinof is probably the person most responsible for the widely held idea that fix participants were “shamed into silence” by their involvement, and that they held to it throughout their lives.

More from Call to the Pen

- Philadelphia Phillies, ready for a stretch run, bomb St. Louis Cardinals

- Philadelphia Phillies: The 4 players on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore

- Boston Red Sox fans should be upset over Mookie Betts’ comment

- Analyzing the Boston Red Sox trade for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen

- 2023 MLB postseason likely to have a strange look without Yankees, Red Sox, Cardinals

While it is true that few of the participants – or for that matter few of their clean teammates – made themselves available to Asinof during his preparation of “Eight Men Out,” they hardly maintained a vow of silence.

In fact, researchers have uncovered more than 100 instances where scandal participants or figures from both –participating teams freely discussed their recollections of it. Eddie Cicotte and Happy Felsch both did so several times, expressing remorse. Chick Gandil sat down for a famous interview with Melvin Durslag in the Sept. 17, 1956 issue of Sports Illustrated in which he discussed his perception of the episode.

Swede Risberg did the same in a 1941 interview with the Oakland Tribune. “Only six men living know the truth,” he said, leaving unclear which two of the accused eight he believed did not have a full grasp of the facts.

In fact, from 1925 onward, only Lefty Williams and Fred McMullin are not on record as having spoken about their perceptions of the scandal on several occasions.

Next. Trout Contract Caps off $1.32B Spent on Four MLB Players. dark

The same is true of teammates and opponents. In a 1940 Sporting News interview with Ed Burns, catcher Ray Schalk denied reports that the team was ‘disgruntled.’ Similarly, in a 1943 interview with the New York World-Telegram, Eddie Collins, the team’s star second baseman, recounted an incident during a 1920 game in which Dickie Kerr accused some of the White Sox players of not giving their best. “If you fellows are throwing this one, let me in on it,” Collins recalls Kerr telling them.