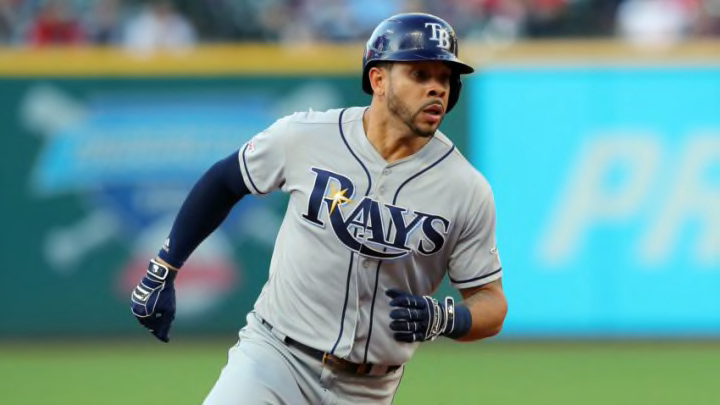

Tampa Bay Rays star Tommy Pham says players on smaller-market teams don’t get an even shake from the fans who vote

For as long as the fans have been involved in selecting the All Star teams, players have griped about fan bias.

In 1957, Cincinnati Reds fans elected seven of their eight stating position players to the National League team. Some of the decisions were so outrageous – like Ted Kluzewski over Stan Musial at first base or Gus Bell and Wally Post ahead of Willie Mays and Hank Aaron in the outfield – that NL President Warren Giles stepped in and ordered lineup changes.

As recently as four years ago, MLB cancelled more than 65 million ballots amid allegations of fraud and ballot stuffing.

More from Call to the Pen

- Philadelphia Phillies, ready for a stretch run, bomb St. Louis Cardinals

- Philadelphia Phillies: The 4 players on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore

- Boston Red Sox fans should be upset over Mookie Betts’ comment

- Analyzing the Boston Red Sox trade for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen

- 2023 MLB postseason likely to have a strange look without Yankees, Red Sox, Cardinals

So it’s no surprise that Tampa Bay Rays outfielder Tommy Pham sounded off this week about voting bias. “Big market vs. small market. It’s never going to be fair,” Pham said.

MLB tried to tweak the process this year, creating a two-round voting system. In the preliminary balloting now underway, votes are tabulated but the top three vote-getters at each position only advance to a second and final round. That’s the round in which the starters will actually be selected.

Based purely on performance, Pham has at least something of a point. He’s batting in the .290s and is a lineup centerpiece for one of baseball’s most surprising contenders, yet he stands only 15th in the outfield voting behind such players as Jackie Bradley Jr. (.205), Max Kepler (.263) and Brett Gardner (.229).

Pham is lobbying for himself, but also for teammates such as Avisail Garcia. He’s also batting .300 and he’s also out of the running for an outfield berth.

Pham notes that it’s not merely about prestige. “When you go into arbitration, that’s a big thing that’s talked about,” he said. He particularly wants networks holding prestige exposure slots – like ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball – to give smaller market teams some exposure instead of continually focusing on the Yankees, Red Sox, Cubs, and Dodgers.

Pham’s interest in the arbitration process is not academic; he becomes arbitration-eligible after this season.

A quick look at the early voting illustrates the extent to which a handful of teams dominate voter interest. Considering the top five American League vote-getters at each position, players on only five teams have received more than 80 percent of all votes cast.

Tampa Bay Rays

Four of those teams – the Astros, Yankees, Angels, and Red Sox –represent the largest markets. The one smaller market team with a strong voter presence, the Minnesota Twins – has the league’s best record.

The same story holds in the National League voting. The Cubs, Dodgers, Braves, Brewers, and Rockies jointly command an 85 percent share of the vote.

At the other end of the scale, eight teams – the Orioles, Blue Jays, Tigers, Mariners, Nationals, Giants, Marlins, and Reds – collectively have zero players among the top five vote-getters at any position. Since all of those teams are sub-.500, it’s fair to assert that voters are making quality judgments.

At the same time, Pham’s Rays have just 3.9 percent of that overall vote, despite a 41-27 record. All of it belongs to outfielder Austin Meadows. Similarly, the Cardinals, Padres, Diamondbacks, and Mets – all close to or above .500 – collectively split just six percent of the vote.

Some years back, Bill James suggested an alternative approach he thought would minimize the prospect of results that were biased by geography or market size. He modeled it after the Electoral College.

James’ idea involved dividing the voting prospects into districts – each district essentially replicating a team’s market – with points assigned to the top few vote-getters in each district. The All Star starters, then, would be the players compiling the largest number of “electoral” votes.

In that fashion, James argued, regional bias would be reduced since while each district might favor its home-town stars, down-ballot voting would be more performance-based.

In that way, he suggested, the merit-based votes would be allowed to out-weigh the favorite-son candidacies.