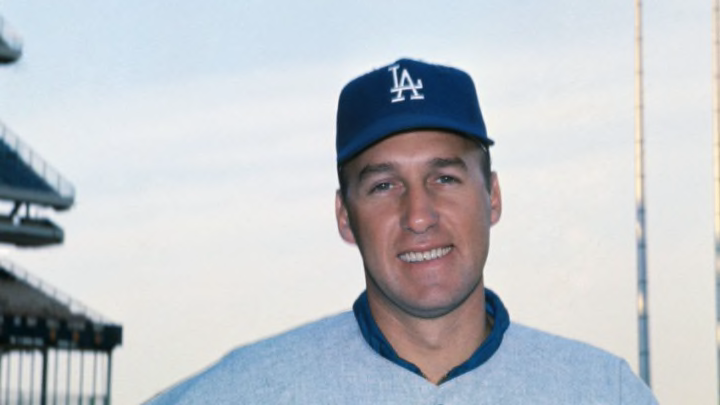

The New York Mets new pitching coach summons memories of a bygone era in the game’s history

When new New York Mets pitching coach Phil Regan came to the major leagues in 1960, his manager was Jimmy Dykes. Dykes in turn made his debut in 1918 playing for Connie Mack, who had debuted in 1886.

Thus it’s fair to say that two degrees of separation from the new Mets pitching coach encompasses all but 10 of the 143 years of Major League Baseball.

The appointment of the 82-year-old Regan prompts all manner of similar nostalgia. His three fellow Mets coaches with significant big league experience – Chili Davis, Gary DiSarcina and Ricky Bones – were active in the 1980s and 1990s, by which time Regan ‘s career had been over for close to two decades.

Bones, who was named interim bullpen coach when Regan was named pitching coach, was just three years old when Reagan retired as a player in 1972. DiSarcina was only four and Davis, aside from Regan the elder statesman of the group, was in middle school.

Regan’s immediate supervisor on the New York Mets, field manager Mickey Callaway, would not be born until 1975, when Regan was three seasons into a post-playing career tenure as head coach at Grand Valley State University.

Because of its reach, a look back at Regan’s career, and especially at his teammates, provides an unusual glimpse into the historical panoply of baseball. The All Star team of his teammates that follows is premised on two factors. One, obviously, is playing accomplishment.

But the second, at least as important and possibly moreso, is age. On this team, it is at least as important to have played during the game’s Golden Era as to have Hall of Fame credentials.