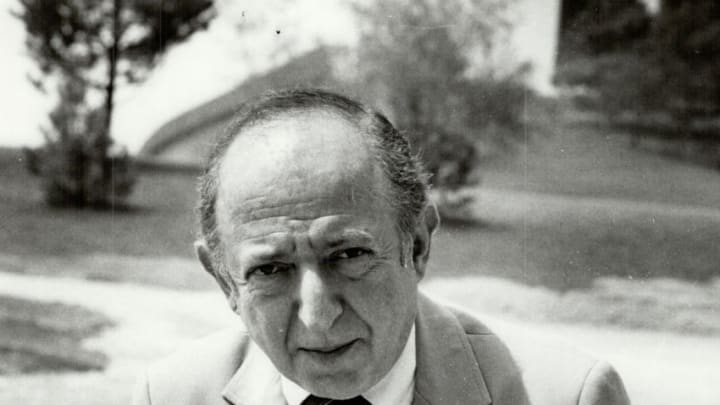

Famed baseball writer Roger Kahn passed away on Thursday at 92 years old.

When Roger Kahn set to work on what became his signature work, The Boys of Summer, ten years after the storied and often star-crossed Dodgers moved from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, he discovered himself against the grain, as he put it himself. An editor dismissed him with, “Those Dodgers are no more special than, say, the Boston Red Sox of 1948. You only think they’re special because you covered them. They’re only special to you.”

That editor was wrong. And Kahn, who did indeed cover the 1952-53 Dodgers as a young reporter on the New York Herald-Tribune, was proven more right than he could have suspected. The Boys of Summer graduated his Dodgers from mere mythology to assured immortality for the generations who knew not from whence they came. Almost paradoxically, too, considering he’d developed his idea when he “began to consider the Dodgers not as baseball players but as baseball-playing men.”

Kahn died Thursday at 92 in Mamaroneck, New York. He was a 24-year-old cub when the Herald-Tribune assigned him to the Dodgers. When Peter Golenbock wrote his own Dodger history, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers, he recalled Kahn as the polar opposite of the other most famous journalist to cover those Dodgers, the acerbic New York Daily News columnist Dick Young:

"Like Dick Young [Kahn] was part of the Brooklyn fabric, a skinny, shy, but aggressive boy trying to be friends with the players and at the same time report objectively about them. Unlike Young, who wrote with a rapier, Kahn rarely criticised, rarely drew their ire. It wasn’t his way. It made him uncomfortable. Better, he felt, to write about the good in people. As a result he was closer to many of the players than were the other reporters, and his relationships with Jackie Robinson, Carl Erskine, Clem Labine, Pee Wee Reese, Carl Furillo, and some of the others continued, even after he left the newspapers."

Kahn was the son of high school teachers; his father, Gordon, was concurrently the informational brains behind a legendary radio quiz show, Information Please, whose genuine intelligence married genial wit in an exercise that proved intellectuals were only human too and some didn’t fear for their reputations or images by showing it. Father and son shared a passion for the “comic opera” Dodgers (Kahn’s phrase) borne during the Depression. Mother Olga was at once proud of her son’s eventual literary success and aghast that baseball so engaged grown men as deeply as it did children.

He moved to covering the New York Giants for 1954 before leaving the Herald-Tribune for the magazine world. His resume from there included such magazines as Sports Illustrated, the Saturday Evening Post, and Newsweek (he was its sports editor for a time), before he joined such writers as Arnold Hano (A Day in the Bleachers) and Ed Linn (among others, Bill Veeck’s collaborator for Veeck–As In Wreck) as a formidable triumvirate at Sport.

At one time Kahn thought to return to newspapering, “but I had seen carpeted offices and Marilyn Monroe. Newspaper days were forever behind me, like games of stickball . . . I was trying to move away from baseball, but my journalistic identity, such as it was, lived with the Tribune stories on the Dodgers.” And, in due course, perhaps taking cues from Jim Brosnan (The Long Season) and Jim Bouton (Ball Four) who reckoned with presenting players living from within baseball’s innards while they still played, Kahn surrendered and elected to reckon with the Dodgers he knew and befriended as men who happened to be former players.

He reckoned with the once-fractured relationship between pitcher Clem Labine and his son, Jay, who’d served in Vietnam and lost a leg. (“We had fights,” Labine said. “Clement Walter Labine, Junior wanted to be different from me and he is different from me and maybe I wanted him to be the same.”) He reckoned with genial pitcher Carl Erskine returning to his native Indiana in hopes that he could make his fourth child, a Down’s syndrome son named Jimmy, “as fully human” as a Down’s child could become. (Asked what his life would have been if he hadn’t pitched, Erskine replied, “I don’t know. It’s like asking what my life would be without Jimmy. Poorer. Different. Who knows how?”)

Kahn moved from listening to 1952 Rookie of the Year Joe Black, the first African-American to win a World Series game, speak of his effectiveness teaching black and white schoolchildren to stop fearing each other, to listening to pinch-hitter/outfielder George Shuba discuss his deep religious faith and family philosophy—and letting Shuba show him the secret to the smooth swing Kahn admired so greatly: six hundred swings daily at a clump of rubber bands made into a ball hanging from a basement rafter.

He reiterated a particular friendship with right fielder Carl Furillo, whose throwing arm was equal only to his stubborn will, who sued baseball over his release from the Dodgers while still injured, and who eventually worked for the elevator company that installed their wares in the World Trade Center. (When Kahn once became a major owner of the minor-league Utica Blue Sox, about which he wrote Good Enough to Dream, Furillo cracked, “You? An owner? You’ll be lucky if you don’t have two ulcers by Opening Day.”) And he even reached reclusive third baseman Billy Cox, tending bar in Pennsylvania, content among strangers . . .

"[who couldn’t] have realised that this broad-shouldered, horse-faced fellow tapping billiard balls, missing half a finger on one hand, sad-eyed, among people who would never be more than strangers, was the most glorious glove on the most glorious team that ever played baseball in the sunlight of Brooklyn."

Los Angeles Dodgers

And, he played straight the contrast between Hall of Famers Jackie Robinson, whose own core gentleness didn’t obstruct a man who suffered no fools gladly especially after he’d proven his barrier breaking was neither fluke nor folly; and, Roy Campanella, who preferred to break the barriers with a smile, a joke, a laugh, a game, a good time.

If timing is everything, Kahn’s when returning to Robinson wasn’t exactly the best of timing. Robinson’s oldest son struggled with substance abuse and legal trouble and, when Kahn revisited the Robinsons while composing The Boys of Summer, the son had been hospitalised after “a scrape” in New Haven, where he was working by then trying to help fellow recovering addicts. Yet bad timing provided one of the book’s most touching passages, since Kahn had taken his own young children to visit “this large, gentle man” he called “the lion at dusk,” before Robinson had to leave to bring his son home:

"When Robinson found [my] older boy wanted to become an architect, he showed him something of how the house was built. My younger son wanted to fish. Robinson found him a pole and baited a hook and pointed out a rock. “That’s the best place to fish from.” He was playing peek-a-boo with my three-year-old daughter when the time came for him to leave. “You and the children stay,” he pleaded. “I wish Rachel could see them playing. That’s what this house was built for, children.”"

Robinson was already weakened by diabetes and a heart attack; he would die of a second heart attack shortly after The Boys of Summer became a best seller. But not before calling Kahn and needling, “Is this the richest writer in the state?”

Kahn continued his career writing for assorted magazines (Shuba once chided him for writing about Students for a Democratic Society and the 1968 Democratic National Convention riot: “He simply did not understand why anyone who was a writer, a craft he respected, would spend time, thought, and typing on the New Left”) and further books (nineteen total), including a pair of anthologies, How the Weather Was and Games We Used to Play.

The latter has two intriguing entries back to back. Kahn wrote a sweet eulogy to Furillo, who died of leukemia in 1989, in which he remembered Furillo’s growth to colour-blindness about race and unblemished wish to take people at their word. And, he followed that with a 1990 piece about Pete Rose, with whom he was collaborating on Pete Rose: My Story, at the very time Rose was banished from baseball for gambling on it.

Kahn called that essay, “Story Without a Hero.” Little did he know. Pete Rose: My Story nearly torpedoed Kahn’s reputation, once the truth Rose denied about his baseball gambling began pouring forth, and left Kahn with what the Los Angeles Times once called “the sting of having his name on a book based on a lie.”

"He was always surrounded with a bodyguard of liars, and so the question had to be put to him, before we went forward with the book. I must have sat him down and asked him five times, “Did you bet on baseball?” And the answer was always the same. He’d look me in the eye and say, “I’ve got too much respect for the game.” I regret I ever got involved in the book. It turns out that Pete Rose was the Vietnam of ballplayers. He once told me he was the best ambassador baseball ever had. I’ve thought about that and wondered why we haven’t sent him to Iran."

Kahn knew other, deeper stings in his life. He grew up with a polio-wracked sister. He was thrice divorced, though he married happily for a fourth time. He was the father of four children, including a daughter who died a day after she was born and a son whose battle with mental illness and drug addiction ended in suicide before he was 24.

And, sadly, too, whispers abound about Kahn finally alienating longtime friends and admirers on several grounds, from heavy drinking to late-day careless writing and reporting. It’s a sad thing to suspect about a man who wrote so humanely about the Dodgers and other subjects, and who once counted among his friends not just vintage Dodgers but poet Robert Frost and presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy.

Better, instead, to remember ithe man who wrote of his beloved Dodgers, “Unlike most, a ball player must confront two deaths. Yes, it is fiercely difficult for the athlete to grow old, but to age with dignity and with courage cuts close to what it is to be a man.”

In ancient days a particularly venomous columnist named Westbrook Pegler, who’d been a sportswriter before turning to politics and eventual rhetorical bomb throwing, observed there were two kinds of sportswriters: “the ones who write ‘gee whiz’ and the ones who write ‘aw, nuts’.” At his absolute best, Roger Kahn did both at once with uncommon lyricism.