Will the Mets really give Luis Rojas a chance to prove his soundness, or will the usual front-office follies make his life tricky as it did for others?

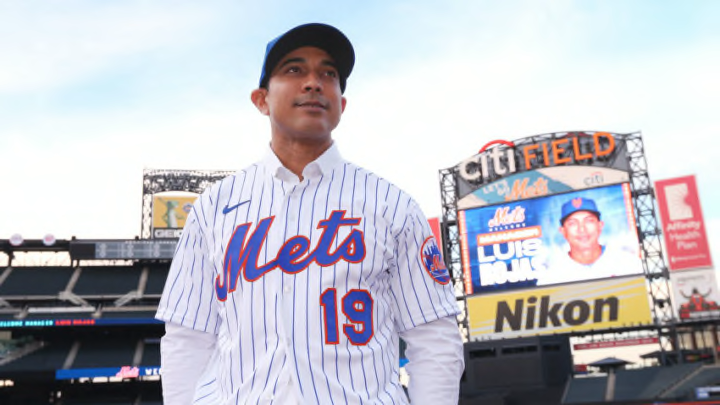

If you take the word of The Athletic‘s Ken Rosenthal, Luis Rojas may be the single most becalmed man in New York baseball, which isn’t simple. He’s the new manager of the New York Mets, and Rosenthal says at least one Mets official compares him rather favorably to another manager who once took on the Mets before sending himself to the Hall of Fame managing the crosstown Yankees.

“The name Joe Torre sound familiar?” Rosenthal asks, not entirely archly.

Rojas wasn’t necessarily a large spot on the Mets’ radar when they hunted for Mickey Callaway‘s successor. But he interviewed twice, the second time feeling like the charm when Rojas came through a kind of test that Rosenthal says included game simulations and mock press conferences. Still.

The Mets interviewed several others, too, before settling on Carlos Beltrán. They believed “the experience he amassed in his 20-year playing career would give [Beltrán] the ability to relate to virtually any player in any situation,” Rosenthal writes. “Beltrán would not have needed to gain credibility in the clubhouse. He would have had it the moment he stepped into the room.”

Until he’d had it, period, thanks to his involvement as the only player named in commissioner Rob Manfred’s Astrogate report. Rojas had accepted the Beltrán hire like a professional and began planning his coming work for a second season as the Mets’ quality control coach. But he had to wait only a week after Beltrán’s purge before the Mets decided he was “the path of least resistance” and handed him the job.

Rojas is very well respected in the Mets’ organization, including by players and fellow coaches. Hitting coach Chili Davis says Rojas “worked his butt off. If it meant sacrificing a little to get it right, he did that. He sacrificed a lot.” Third base coach Gary DiSarcina, who’d been the deposed Callaway’s bench coach at first, says he’s “come out of his shell.”

DiSarcina often noticed Rojas talking to players very often without being a presence, Rosenthal writes. “He was so quiet, so immersed in his work, trying to be successful at the major-league level,” DiSarcina says. “When I heard he got the job, my first thought was, Can he command the room? When that manager walks in the room, especially with the entire organization gathered for that first speech, how is he going to do? I thought he knocked it out of the park.”

And Rojas, whose previous experience includes managing in the Mets’ system, has the respect going in of two of the team’s young keys, Rookie of the Year Pete Alonso and Jeff McNeil. He also seems to be fortifying respect among other players just as the coaching staff has his back. What, Rosenthal wonders, could possibly go wrong, before answering as just about every Met fan does—the front office.

The Mets’ owners aren’t half as colourful as the late Yankee owner George Steinbrenner, but the Wilpons have been no less the buttinski types with more than a degree of know-it-all-ism while they’re at it. They don’t have Steinbrenner’s knack for the insultingly colourful phrase, but they have his longtime genius for pointing the way to wisdom by pointing the other way.

Rojas speaks with far more surety than Callaway turned out to have in the nuclear heat that is New York sports. Callaway was open, sharp, and accommodating as the Cleveland Indians’ pitching coach. As the Mets’ manager, he proved tactically challenged and as clumsy as the day was long in controversy, particularly when he snapped at a reporter before having to apologize twice, just as clumsily, following a game-costing tactical mishap in Chicago he had to have known every reporter in the room would question.

Now the Los Angeles Angels’ pitching coach, Callaway himself respects Rojas’s diligence. “No matter how tedious the task was,” he tells Rosenthal, “he was willing to tackle it and kind of make it his own.” Davis says Rojas’s lack of fear about asking advice should work big in his favor.

“We’ve got lots of sets of eyes paying attention to the game for him,” the hitting coach continues. “He’s the type of person, he’ll ask advice. And we’ll give him advice. The ultimate decision will be made by him, but he’s going to have enough information to make very calculated decisions.”

That side of Rojas showed up early and often as the Mets got spring training underway. Veteran catcher Wilson Ramos got his reminder while the team drilled cutoffs and relays. “Wilson said, ‘Hey Luis, why don’t we have the middle infielders throw the ball in the air from the line, instead of the long hop. From the left field line, it’s tough having to stretch out for that throw and then do a swipe tag’,’’ the new skipper told the New York Post a week ago.

Approvingly.

“[Y]ou always felt comfortable going up to him, telling him exactly what you were feeling,” says Mets outfielder Michael Conforto, who also played for Rojas in the minors. “He wanted to hear your thoughts on certain plays and he wanted to try to understand them, instead of hear them and tell you that you are wrong. He was hard on us at the same time. He’s got all the things you want in a manager. His steadiness will be good in this market.”

New York Mets

Two weeks before the Ramos drill question, the Post revealed the Mets got serious about developing a new organisational way to play, shepherded by Allard Baird, the former Kansas City Royals general manager, in his second year directing the Mets’ scouting and player development. In over his head as a GM, Baird proved a more successful scouting overseer in three seasons and three World Series championships with the Boston Red Sox.

Baird’s new approach and plan begins by asking young players how they want to be remembered as players. It continues by fortifying the fundamentals to be taught before, not when they reach the Show. Rojas is on board completely. It fits his own developmental philosophy as well as his approach to running a game and keeping his players focused.

It sounds like a thorough top-down steeping in baseball smarts often thought to have eluded Mets adminstrators in the past. It sounds like the Mets want to say when, not if the world will stop seeing mishaps as, “That’s so Mets.”

Even general manager Brodie Van Wagenen isn’t worried—yet. “He’s going to provide a strong tone in which he delivers his message,” he tells Rosenthal. “He’s going to be focused on the fundamentals, player development at the major-league level and communicating across all demographics and cultures within our clubhouse.”

Discipline? Callaway exposed himself as an inconsistent disciplinarian last year, refusing to bench pricey veteran Robinson Cano for lackadaisical effort but subsequently benching far younger, far less expensive shortstop Amed Rosario for an exact match in lack of effort while waving it off as giving him a day off. Callaway also failed to suspend subsequently-traded pitcher Jason Vargas for threatening violence against the same reporter in Chicago after the same tactical mishap.

Some, including Rosenthal, speculate Callaway, already under fire in a rickety first half, struggled with his priorities before “losing his way” trying to keep pleasing his bosses. They wonder whether the far more composed Rojas might run into the same syndrome without realizing it.

For now, though, Rojas wants his Mets to become known as a team that plays soundly and leaves no mistaken impressions. And his players are all aboard. “We want to get into a town and we want to be acknowledged,’’ he told the Post. “‘Hey, the Mets do this: Go first to third, score from first on doubles, score from second on singles. They make the plays. They are fundamentally sound’ . . . We want the feedback from the players and the coaches. How we do things, there can always be more ideas.”

Will the steadiness Conforto praises be enough for Rojas to survive the caprices and comedies of the Wilpons if they remain the Mets’ owners for the season or two to come at least? Can Rojas keep the ship on course the next time a Wilpon decision (indecision?) means an issue unresolved or overthrown, or a key acquisition possibility turned to vapors?

The Mets are 1-5 in spring training exhibitions so far. They’re more concerned about getting into the regular season in sound shape. They were encouraged by two scoreless innings from Rick Porcello, their new veteran starter, in a Thursday loss, especially the way he pitched out of first inning trouble. Likewise the single scoreless innings each thrown by bullpen bulls Brad Brach and Robert Gsellman, making cases for their middle-relief presences.

And the word is that Edwin Diaz, whose 2019 was a disaster especially when his once-vaunted slider went AWOL, has begun rediscovering the pitch and its proper movement, little by little, enough to make you think 2019 may prove his outlier season after all.

The hitters have their spring kinks to work out, too, of course. But the early returns despite the record suggest the new skipper’s thinking, while navigating the organisation’s refined way of thinking, could equal big returns on the regular season.

All the Mets have to do is get out of their own way and let Rojas and his staff do their jobs. Mets history, alas, suggests that may be easier said than executed.