The MLB Hall of Fame needs to induct two more players as pioneers – Curt Flood and Andy Messersmith.

Before the turn of the century, George F. Will observed that once upon a time two-thirds of the earth was covered by water and the rest was covered by Curt Flood. And Flood won the Gold Gloves Willie Mays didn’t in center field to prove it.

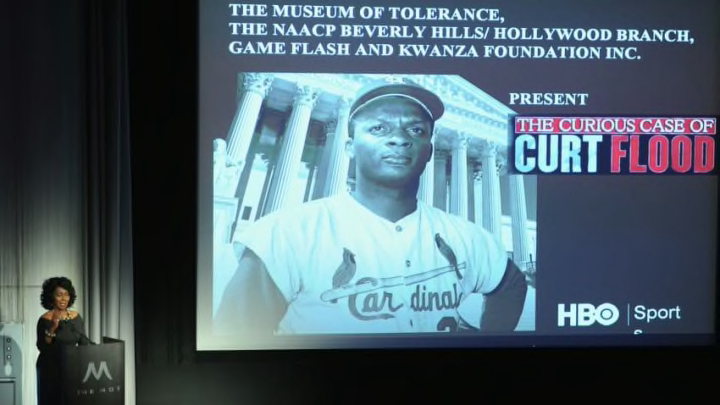

How Flood is remembered most, of course, isn’t as a cover-the-earth center fielder who could hit, but as the quietly bristling fellow who kicked a stubbornly closed baseball door open when he rejected a trade from the St. Louis Cardinals to the Philadelphia Phillies.

There are many who think that qualifies him for the Hall of Fame on pioneer grounds. They now include a few members of Congress, about whom it’s usually fair to say that when they cast their eyes upon baseball, baseball should beware turning to stone before looking back.

“What Curt Flood did and championed is resonating throughout professional sports for the past fifty years,” says Rep. David Trone (D-Maryland), who’s leading the push to send Flood to Cooperstown at last. Flood’s widow, the actress Judy Pace-Flood, is no less emphatic when she says the holdup has been because her husband “got on a lot of people’s nerves.”

Flood fired the second shot heard ’round the world one not so foggy Christmas Eve, in 1969. On the stationery of his St. Louis portraiture studio (he was talented enough an artist that his portrait of Cardinals owner Gussie Busch hung in Busch’s yacht), Flood informed commissioner Bowie Kuhn “that any system which produces” his trade that signified him as mere property, “that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several states.”

The right that every American otherwise had to negotiate on a free, fair, open job market in his or her chosen profession. That animated Flood far more than his potential salary. (“A $90,000 slave is still a slave,” he said famously about lacking that right.) Baseball’s lords threw their hands up and proclaimed Armageddon approached.

There were two ironies in Flood’s shot. One was the man for whom he was traded, should-be Hall of Famer Dick Allen, whose torments at the hands of Philadelphia racists must have left him feeling as though the trade was his Emancipation Proclamation—even though Allen supported Flood’s shot.

The second: It was in St. Louis where a runaway slave named Dred Scott took his case to court in 1846. Will, who once called Flood “Dred Scott in spikes,” wrote in the same essay, “[Scott] was not the last time that the Supreme Court would blunder when asked when a man can be treated like someone’s property.” Which is what the Supreme Court did ruling against Flood at last, in 1972.

To this day there are many enough who think Flood himself ended the reserve era. If only. Flood forced people of sound mind to think and rethink the depth of baseball’s abused and abusive reserve system. But the door Flood kicked ajar with a bang still required a couple of more booming hits to yield.

The first came from Hall of Fame pitcher Catfish Hunter. Made a free agent when Oakland Athletics owner Charles Finley reneged on contracted-for insurance payments, Hunter became the target of a bidding war in the millions. He finally signed with the New York Yankees, for less than was offered by a couple of other teams, because the Yankees were willing to satisfy things beyond pure dollars. Things like annuities to guarantee his children’s education.

Even that was a bunt compared to the grand salami to come. It came from a Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher who was so offended that their general manager injected personal issues into their contract talks that he refused to sign a deal that didn’t include a no-trade clause . . . and to talk to anyone lower than team president Peter O’Malley.

Andy Messersmith was one of baseball’s best pitchers when he pitched 1975 with no contract, refusing to sign no matter how the Dodgers sweetened the pot-to-be, continuing to make life miserable for National League batters. (He led the league with seven shutouts and a 6.8 hits-per-nine-innings rate, with his 2.29 ERA second in the league.)

“The money was incredible,” Messersmith would remember, the offers going as high as $440,000 for three years, including the incumbent 1975, “but they wouldn’t bring the no-trade clause to the table . . . Now I understood the significance of what this was all about. I was tired of players having no power and no rights.”

At season’s end, Messersmith took it to an arbitrator. (Retired but technically un-signed pitcher Dave McNally had signed on as insurance in case Messersmith wavered.) He fought baseball’s law and the law didn’t win this time.

“Curt Flood stood up for us,” said very eventual Hall of Fame catcher Ted Simmons upon the Messersmith ruling. “[Catfish] Hunter showed what was out there. Andy showed us the way. Andy made it happen for us all. It’s what showed a new life.”

Flood’s career ended almost immediately. Messersmith signed a free agency deal with the Atlanta Braves but ran into shoulder injuries that ultimately put paid to his career. The pioneers too often see their fruits grow strongest on trees other than their own.

Flood’s Christmas Eve letter was the players’ Declaration of Independence. Messersmith won Yorktown. Trone and his Congressional colleagues may not do anything much more than augment the arguments made long enough. But they really should proclaim that, on such pioneer grounds, Flood and Messersmith belong together in the Hall of Fame.