MLB: The history of baseball in seven degrees of separation

In only seven degrees of separation it’s possible to encompass 143 seasons of MLB history. Start with C.C. Sabathia and get to Cap Anson.

There was a very interesting article published today at mlb.com examining how far back in baseball history it was possible to reach linking players who actually hit or pitched against one another.

In the piece “How far back in HR history can we go in six steps”, Michael Clair applied the “six degrees of separation” principle to reach from Giancarlo Stanton of the present-day New York Yankees all the way back to Bob Feller of the 1937 Cleveland Indians.

More from Call to the Pen

- Philadelphia Phillies, ready for a stretch run, bomb St. Louis Cardinals

- Philadelphia Phillies: The 4 players on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore

- Boston Red Sox fans should be upset over Mookie Betts’ comment

- Analyzing the Boston Red Sox trade for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen

- 2023 MLB postseason likely to have a strange look without Yankees, Red Sox, Cardinals

His common bond: one of the players either had to have homered off of, or given up a home run to, the other.

It’s an interesting premise, but we can do better. With only a slight liberalization of the rules, we can encompass the entire 143-year history of the major leagues by adding only one more degree of separation.

The slight liberalization of the rules is as follows: Rather than one of the players having homered off or allowed a home run to the other, we will only require that the two players have actually played with or against one another in the same major league game.

We’re also taking one quick liberality with the definition of an “active” major leaguer. Since no games have been played yet in 2020, we are starting with players who were active in 2019, specifically C.C. Sabathia. Yes, we know Sabathia announced his retirement at season’s end. Yes, that will be a problem for this premise as soon as games resume. No, that hasn’t happened yet.

Our journey through baseball’s time capsule will touch on some of the game’s immortals, including five Hall of Famers. The other three fall short of that designation — in one case for now, anyway — but they were also first-rate players.

With that as an explainer, here are seven degrees of separation through baseball history

MLB History in Seven Degrees of Separation

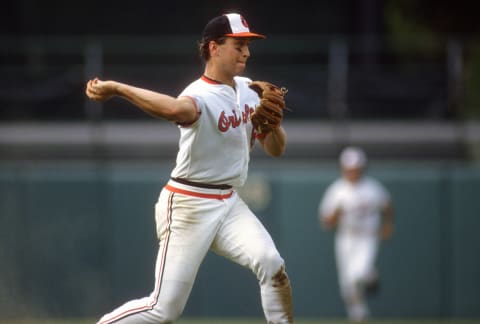

Degree 1: April 8, 2001

On this date, 20-year-old Indians pitching prospect C.C. Sabathia made his major league debut against the Baltimore Orioles. Sabathia would in time compile a 251-161 big league record, and 3.74 ERA, but that was the merest gleam in his eye as he took the mound.

Sabathia’s focus, rather, was on contributing to lofty hopes in Cleveland. The Indians had finished second in the AL Central, just one game behind the wild card Seattle Mariners, in 2000, and hoped to contend in 2001. In fact they would win the AL Central before being eliminated in the division series by those same Mariners.

Sabathia would blossom into an immediate e sensation, compiling a 17-5 record in 33 starts.

His opponents that debut day was the Baltimore Orioles, a team of whom little was expected. The Orioles had finished fourth in the AL East the previous season, and although they stood 3-2 entering their April 8 meeting with Sabathia not much more was expected.

Related Story. The shortened 2020 MLB season would be historic. light

But the Orioles lineup featured one of the best-recognized names in baseball history, third baseman Cal Ripken. At 40, Ripken was in the final season of a 21-year big league career that had seen him break Lou Gehrig’s record for consecutive games played.

On this day, Ripken faced Sabathia twice. In the second inning he groundout out to Indians shortstop Omar Vizquel, and in the fourth he flied to left, ending that inning.

Sabathia was removed with two out in the sixth inning, the Orioles leading 3-2. Cleveland rallied for two runs in the seventh and a 4-3 win, Sabathia receiving a no-decision.

MLB History in Seven Degrees of Separation

Degree 2: Aug. 28, 1981

Cal Ripken may have been on his way to a Hall of Fame career, but on Aug. 29, 1981 he was just a 20-year-old rookie two weeks out of the minors who got a big-league call when the mid-season strike ended.

By Baltimore’s Aug. 27 game with the California Angels, he remained a part-time infielder making occasional starts and trying to convince Orioles manager Earl Weaver that he belonged.

Weaver started Ripken at shortstop that night in Baltimore, batting him ninth. He hit that low for a reason: Ripken to that point was off to a .103 start, having gone hitless the previous night in five at-bats against Seattle’s Glenn Abbott.

The Orioles were in the midst of a historically frustrating season. In the strike-occasioned split-season format that governed during 1981, they had finished second in their division behind the Yankees during the first half, and they would come home fourth, although at 28-23, during the second half. That meant that despite having the division’s second-best record, they would be shut out of the expanded post-season schedule.

The visiting Angels were going nowhere. Their lineup that night featured a veteran cast that had largely under-performed, and which would finish the season at 51-59, well out of contention. Baltimore won the game in question 6-2 behind Scott McGregor, who pitched a complete-game six-hitter.

Ripken found no quick answers to his hitting woes, striking out against Ken Forsch in the second, and grounding out to third base in the fifth. He was removed in favor of pinch hitter Terry Crowley in the seventh inning of a 1-1 tie; Baltimore scored four times in the eighth to win.

Among the under-performing notables in the Angel s lineup was Ripken’s opposite number at shortstop, 39-year-old Bert Campaneris. He was concluding a 19-season career that included roles with the World Series-winning Oakland Athletics of 1972-74.

Signed as a free agent by Texas in 1976, he spent three seasons there before being traded to the Angels midway through the 1979 season.

Campy managed one of his team’s five hits against McGregor, a first-inning bunt single with Rod Carew at first that the Angels failed to take advantage of.

McGregor retired Campaneris on a fly ball in the third inning and fanned him in the sixth. In the seventh inning, Angels manager Gene Mauch pinch-hit Juan Beniquez for Campaneris and he grounded out.

MLB History in Seven Degrees of Separation

Degree 3: Aug. 2, 1964

Bert Campaneris was a 20-year-old prospect out of Cuba when Charley Finley signed him to a Kansas City Athletics contract. Within two years he was in the majors, providing a rare breath of hope on a very bad Athletics team.

Campaneris debuted July 23, 1964 against the Minnesota Twins and collected three hits, two of them home runs. It was misleading; Campaneris wasn’t built like a power hitter and he would never become one, only once hitting more than eight home runs in a season.

Ten days into Campaneris’ career, the Baltimore Orioles provided the opposition. The Athletics were 40-65, the Orioles 65-40, and in a virtual tie for first place with the New York Yankees. So the game meant a lot more to the Orioles than to the A’s.

That being so, Orioles manager Hank Bauer sent the one experienced member of his young pitching staff out to the mound. At 37, Robin Roberts was a 16-year veteran with more than 250 big league wins and less on his fastball than had been the case a few years before.

The Orioles signed Roberts as a free agent in 1962 largely to tutor the developing arms, Steve Barber, Dave McNally, and Wally Bunker…but also to pitch in a few games of importance. Roberts would make 31 starts in 1964, of which this was No. 21. He stood 8-5 on the way to a 13-7 overall record.

Related Story. MLB: pitcher Ron Necciai and a feat never to be duplicated. light

After Baltimore touched KC starter Diego Segui for a first-inning run, Campaneris led off against Roberts with his first home run since the two he had hit in his debut. Coming up again with two out and a runner on first in the bottom of the second of a 3-2 Orioles lead, he dropped a single into right field that pushed Nelson Mathews to second base. But Mathews died there when Roberts retired Wayne Causey.

Bauer removed Roberts in the fourth inning, his Orioles leading 7-3 but Kansas City threatening. Barber came in, worked around Campaneris’ third hit of the game, and held on to pick up an 8-7 win.

Roberts continued to pitch until 1966 when he went 5-8 as a 39-year-old in 22 starts for the Astros and Cubs.

MLB History in Seven Degrees of Separation

Degree 4: The 1948 season

Robin Roberts never pitched against Schoolboy Rowe, but he certainly pitched with him. When the Phillies called the 21-year-old Roberts up in June of 1948, Rowe was as close as the Phillies had to a star.

Purchased from Brooklyn prior to the 1943 season, Rowe by 1938 was a 38-year-old veteran of 14 big league seasons. He would retire one year later with a 158-101 record and a 1935 World Series title he won as an ace of the Detroit Tigers staff.

Rowe was 10-10 in 20 starts for the Phillies in 1948, compiling a 4.07 ERA.

Roberts made his debut June 18 against the Pittsburgh Pirates, taking a 2-0 loss. One day later Rowe took the mound, lasting eight innings in a 7-6 defeat to the same Pirates.

On July 18 Roberts started the first game of a doubleheader against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. He pitched a complete game but lost 3-2. Twenty minutes later, Rowe started the second game and lasted six innings, the Phillies winning 6-4.

Their paths crossed frequently for the rest of the season.

On Aug. 23 at Crosley Field, Roberts started and pitched seven innings. Rowe relieved in the ninth and took a 3-2 loss on Reds pitcher Harry Gumbert’s 10th inning home run. On Sept. 6 at Shine Park. Roberts started and pitched nine innings against the Giants, leaving for a pinch hitter in the bottom of the ninth. When the game went into extra innings, Rowe relieved and produced two more scoreless innings only to see New York eventually win in 13.

Rowe retired in September of 1949, by which time Roberts was recognized as one of the National League’s pitching stars.

MLB History in Seven Degrees of Separation

Degree 5: July 9, 1933

In July of 1933, Lynwood Rowe was a 23-year-old rookie on the fast track to making a name for himself. Having debuted less than three months earlier, the baby-faced kid everybody called “Schoolboy” made the 13th start of his career against one of the toughest tests he could imagine: the vaunted New York Yankees.

To that point Rowe’s rookie season had been full of promise. He had won six of his 10 starts, was recently coming off a stretch of six consecutive complete games, and had produced an ERA barely above 3.20. To put that in context, the league ERA in 1933 was 4.28.

But facing the Yankees in the first game of a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium was certain to be a particular challenge. Although New York would not win the American League pennant, the Yanks were the defending World Series winners, having swept the Chicago Cubs in four games in 1932. Lou Gehrig, Tony Lazzeri, and Bill Dickey were still in their primes.

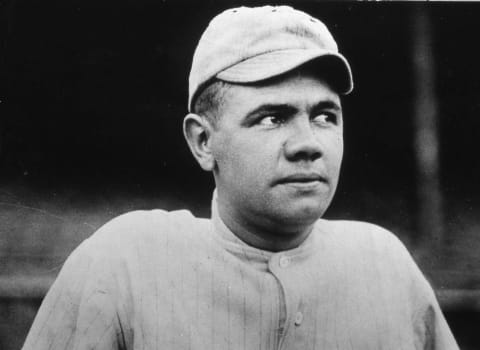

And then there was Babe Ruth.

Related Story. MLB Hall of Fame: That challenging first-year eligibility. light

Ruth was 38 in 1933, and his best days were certainly behind him. Yet he remained an effective hitter, on his way to a .301 average 34 home runs and 104 RBIs. He would also draw a league-leading 104 walks.

On this day Ruth gave Rowe a lesson on what playing in the major leagues meant. The Tigers led 4-1 when Rowe faced Ruth with Dixie Walker at second base in the third inning. The Babe shot a ball into the right-field bleachers for a two-run home run.

Ruth’s second home run, also to right field in the fifth, tied the game at 6-6 and knocked Rowe out of the box. The Yankees went on to win 11-7.

MLB History in Seven Degrees of Separation

Degree 6: July 11, 1914

“Passing of the torch” games are rarely recognized at the moment. Certainly the notion of Babe Ruth as the game’s greatest slugger was in nobody’s imagination when Ruth made his major league debut against the Cleveland Naps that July day. At 19, he was an immature, hard-throwing pitching prospect the Red Sox had purchased from Jack Dunn’s Baltimore minor league powerhouse.

Red Sox manager Bill Carrigan had a developing ballclub that year; the Sox would finish 91-62 and one season later win their first of three World Series titles in four seasons. Although Ruth would in time play a large part in that success, he wasn’t ready yet. His 1914 workload would consist of just four appearances, two of them victories.

Carrigan sent Ruth out first to face a team loaded with once or future stars but struggling through a disastrous 1914. Cleveland entered the game at 26-50 and in last place in the American League. The Red Sox, 41-38, were sixth, but only five games out of first in a tightly bunched race.

The Cleveland star certainly was right fielder Shoeless Joe Jackson, batting .337 in what would be his final full year with the team before being traded to the Chicago White Sox. Three seasons earlier, Jackson had batted .408 but failed to win the batting title because Ty Cobb hit. .419.

The Naps, who at season’s end would be re-designated as the Indians, bore the name of their long-time star, second baseman Napoleon Lajoie, and it was Lajoie’s presence which, if only in retrospect, makes this afternoon one of the defining “passing the torch” games of all time.

A lifetime .338 hitter, Lajoie had batted .426 in 1901, then signed with Cleveland and won three more batting titles. But by the time he faced off against Ruth in 1914, he was 39 years old and very much at the tail end of his career,

Lajoie batted cleanup for the Naps that afternoon in Boston, right behind Jackson. But the matchup of the over-the-hill hero vs. the budding star turned out to be a mismatch. Ruth retired Lajoie all four times they met, the Cleveland legend coming closest to a hit in the sixth inning when Tris Speaker intercepted Lajoie’s sinking drive to center.

Two innings later Speaker made a winner out of Ruth when his base hit drove home Duffy Lewis, who had doubled moments earlier as a pinch hitter for the neophyte Red Sox pitcher. The final was 4-3.

Lajoie retired at the season’s end.

MLB History in Seven Degrees of Separation

Degree 7: Sept. 8, 1896

Napoleon Lajoie was just a 21-year-old recruit with a fancy name when he made his major league debut in August of 1896. Less than two weeks later, Lajoie crossed paths with the game’s reigning immortal, 44-year-old Adrian C. “Cap” Anson of the Chicago Colts.

Anson had been a big leaguer since the National League began, playing in Chicago’s first game on April 25, 1876. Before that, Anson had been a pro in the loosely organized National Association since 1871, playing for Rockford and then for the Athletics of Philadelphia.

More from MLB History

- Analyzing the Boston Red Sox trade for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen

- 5 MLB players who are human cheat codes for Immaculate Grid

- Good MLB players in different uniforms: A look at a random year and two random teams

- Sticky fingers: The pine tar incident, New York Yankees, Kansas City Royals and Gaylord Perry

- Chicago Cubs scoring 36 runs in two games? That’s nothing compared to this historic mark

His teams won National League pennants in 1876, 1880, 1881, 1882, 1885, and 1886. By 1896 though, Anson’s game had slowed, although with a .331 average he could still swing the bat. But he was a liability in the field and on the bases.

Lajoie was everything that Anson had once been. He debuted with the Phillies following as brief professional introduction with Fall River in the Class B New England League. The scouts who signed Lajoie on the basis of that little evidence certainly earned their money; he hit .326 as a rookie and never dipped below .300 until 1908

Over time Lajoie would win five batting titles, most notably that sensational .426 season with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1901.

Anson and Lajoie met several times between Lajoie’s arrival and Anson’s departure following the 1897 season. Possibly their earliest meeting occurred Sept. 8 at Chicago’s West Side Park. Lajoie got an early chance to contribute, batting with a runner on base and one run already across against Colts starter Clark Griffith. But he could manage nothing more than an easy ground out that ended the inning.

Anson failed to contribute to a three-run bottom of the first, but in the second his long fly carried over the head of center fielder Duff Cooley, allowing two base runners to score and sending Anson to third with a triple. Chicago would go on to win 7-3. Anson added a single and stolen base to his run-producing triple; Lajoie managed one hit in four at-bats off Griffith, who also struck him out once.

And there you have the history of 143 seasons of baseball in seven interludes:

dark. Next. Baltimore Orioles uniform analysis, 1971 to 1988

C.C. Sabathia met Cal Ripken in August of 2001. Ripken played against Bert Campaneris in August of 1981. Bert Campaneris faced Robin Roberts in August of 1964. Robin Roberts played with Schoolboy Rowe in 1948. Schoolboy Rowe faced Babe Ruth in July of 1933. Babe Ruth faced Napoleon Lajoie in July of 1914. Napoleon Lajoie met Cap Anson in September of 1896. Cap Anson played in the first major league season in April of 1876.