MLB history: Forgotten stars of the current AL Central teams

We continue our series of forgotten MLB stars by looking around the AL Central.

Here’s a shocker: The negotiations for the start of the 2020 season haven’t gone any better lately, and the start of any baseball season this summer is as unclear as ever. Therefore, it’s clearly time for another in the Call to the Pen series dedicated to forgotten stars of your favorite MLB teams. Today, we will consider five lost luminaries from America’s Heartland, the AL Central.

Clint Hurdle, Royals

Most baseball fans now know CIint Hurdle as a long-time manager of two MLB teams, the Rockies and Pirates, but at this point, few likely recall he was a youthful “phenom,” so anointed by Sports Illustrated in 1978. None other than the venerable hitting coach Charlie Lau called him the best prospect he’d ever seen in Kansas City’s system.

Unfortunately, as a player, Hurdle turned out to be a bit like Billy Beane, a later can’t-miss talent, but not quite so bad as Beane overall. As a player.

In fact, Hurdle had a brief flash of greatness after his build-up. At 22, he had his arguably best season for the AL Champion Royals, a very good team (then in the AL West) featuring George Brett’s .390 season and a .326 season from Willie Wilson.

Hurdle appeared in 130 games that year, almost exclusively in right field. He hit .294 with 31 doubles and 60 RBI. In his team’s eventual loss to the Phillies in the World Series, he hit .417 in four games, stole a base, and scored a run. Unfortunately, this year was the last in which Hurdle played over 100 games.

What exactly happened is a bit mysterious. It may be the Hurdle just hit a wall in terms of how much he was impressing KC management the following year, when he appeared in only 28 games (but hit .329 and drove in 15 runs in only 89 plate appearances). After the season he was traded to the Reds, and then bounced between triple-A and MLB in that organization, as well as with the Mets and Cardinals.

It may be that what Sabr.org calls his off-field “nightlife and the fast lane” had something to do with Hurdle’s stalling out as a player. He is an admitted recovering alcoholic, and is now an advocate for addiction recovery programs.

Clint Hurdle ultimately made a bit more of a mark as a manager, finally winning the NL pennant with the 2007 Rockies. For a brief period, though, he made his money playing the game excellently in a championship season, with several multi-hit games.

A World Series title may well escape him, however, both as a player and manager.

Pete Fox, Tigers

For Detroit’s forgotten star, we need to go back to a loaded Tigers squad, their first World Series champion, and the year 1935. As an original AL team, the Striped Cats fans waited 35 years for that title, but a great team did the trick in the middle of the Great Depression.

Those Tigers included the great Hank Greenberg, Mickey Cochrane, and Charlie Gehringer, who all hit at least .319 that season. Greenberg drove in a ridiculous 168 runs. The pitchers were led by Schoolboy Rowe and Tommy Bridges, who won 40 games between them.

Lost in the shuffle, then, was the right fielder, Pete Fox.

Fox was a lifetime .298 hitter and surpassed .300 five times in his career, but the winter between the Tigers’ loss to the Cardinals in the ’34 World Series and the opening of the ’35 season was one of discontent for the outfielder.

A teammate, Goose Goslin, had made cutting remarks about him to a reporter from his hometown, Evansville, IN. The reporter informed the locals, of course, and Fox became determined to better Detroit’s leftfielder in every category possible when the season started.

At 5-foot-11, 165, he apparently made up for his size with intensity. He didn’t speak to Goslin for the entire season, and in fact, the Fox did pass the Goose in most offensive and defensive categories by the end of the year.

Fox then led the Tigers in hitting in the World Series, posting a .385 average and driving in four runs on 10 hits, including three doubles and a triple.

The ’35 campaign was the first of three in a row in which he hit over .300. However, his only All-Star year came after his trade to the Red Sox, at the age of 35.

A .327 hitter in three World Series for Detroit, though, Fox should be honored in the collective memory of Tigers fans primarily as the guy Goose Goslin annoyed at just the right time.

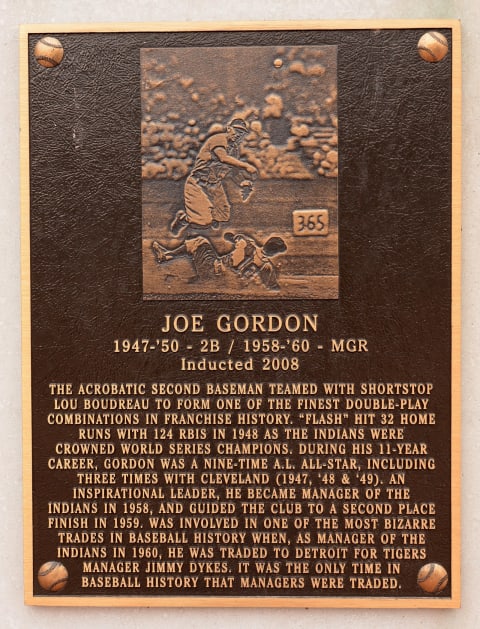

Joe Gordon, Indians

“Wait,” you may be saying, “wasn’t Joe Gordon a Yankee?” Indeed, he was. On his Hall of Fame plaque, he is wearing his New York cap, and for seven of his 11 years in MLB, Gordon wore that hat.

However, for four of the five years of his career after two years of military service during World War II, Gordon was an important part of the Cleveland Indians and a very important part of the 1948 world championship squad, one of only two Cleveland has had.

A quick glance at Gordon’s career numbers suggest he may have cruised into the Hall based on his having played for the powerhouse Yankees of the late ’30s and on another championship team for a year. Nothing succeeds like winning, as the saying goes.

However, Joe McCarthy said after the Yankees World Series win in ’41, “The greatest all-around ballplayer I ever saw, and I don’t bar any of them, is Joe Gordon.” High praise indeed, considering his teammates.

Gordon was known for his acrobatic play in the field although his career fielding percentage was a point below the league’s average for his time in MLB. The guy just got to a lot more balls, apparently.

In 1946, though, things did not go well for him. Returning from the service, he suffered a rash of injuries starting with a spiking injury that severed a tendon in his hand in spring training. After the season, he was traded to the Indians for Allie Reynolds, a very good trade for both clubs.

In ’47, Gordon’s first year with the Indians, he was instrumental in the other players on the team accepting Larry Doby, the AL’s first African-American player. After hitting .272 that year after his injury-plagued .210 the year before, Gordon had his best offensive year for the Indians in their second championship run.

He drove in 124 runs and hit .280. In the World Series against the Braves, Gordon set off the winning Cleveland rally in game six with a solo homer.

At retirement, he had accumulated an MVP award (’42), nine All-Star appearances, the respect of his peers and greats such as Rogers Hornsby, and several World Series rings (or watches – you get to look that up.)

Did he accumulate some honors because he was a Yankee? Sure – that selection as an All-Star in ’46 seems a little odd. But it’s more likely Joe Gordon was one of those guys whose numbers don’t tell the story of his real value.

Eddie Murphy, White Sox

The problem with picking a forgotten star from the world champion White Sox of 1917 is that many of the infamous Black Sox also populated that team, and most of their names are known.

Two years before Baseball’s Great Sin, the team included five or six players who were potential Hall of Famers, one who was a seeming lock, and three who were eventually inducted. The name Eddie Murphy, however, does not leap to mind when the team is mentioned.

Eddie Murphy was eventually known as “Honest Eddie,” in contrast to eight of his teammates in ’19. He was a speedy, talented left-handed hitter who was deemed valuable by two very good teams of his playing era, the Athletics and the White Sox. He eventually appeared in three World Series, but was not on the ’17 Chisox World Series squad despite hitting .317 and driving in 16 runs in only 64 plate appearances in the regular season.

Murphy was basically a utilityman and pinch-hitter for the better part of his career after appearing in at least 137 games a season for Philadelphia and Chicago from 1913 through ’15. After playing one college season at Villanova in 1911, he would play second, third, left, and right.

But in 1917 he began an impressive run as a White Sox bench player despite averaging only 58 game-appearances a year. In that stretch, however, as he eased into the pinch-hitter’s role, he batted .314, .297, .486, and .339.

A simple counting exercise reveals that the .486 year was the MLB scandal year. This time, Murphy was included on the World Series roster, but he made only three pinch-hitting appearances, reaching base once (an HBP).

That makes all the more interesting his claim that Kid Gleason, the Chicago manager, challenged his team to win the Series after game three, remarking, “I hear that $100,000 is to change hands if we lose.”

This, of course, begs a question: If Gleason suspected something was up with his regular players, why not give the guy who had led the AL in pinch hits during the regular season (8) a few more at-bats?

Randy Bush, Twins

Like others among our forgotten MLB “stars,” Randy Bush was a star only if you sort of squint at his career year. Well, maybe you don’t have to squint, but it is true the only year that counts in a long view of his career was the 1991 Twins world championship season.

Let’s be clear, though. Despite a nice little showing in ’91, Bush is arguably guy who only hung on in MLB for 12 years. The Twins had to see something in him, however. They were his only team.

But like Clint Hurdle, Bush also had a moment in the sun – or more accurately, a world championship season in the sun.

As a player who amassed a 1.4 career WAR figure in 12 years, it might be reasonable to assume that Bush had to fight his way into the majors, and he did. He played college ball at the University of New Orleans, summer ball in the Cape Cod League, then needed almost three years in MiLB before breaking in with the Twins in 1982.

At first, he was used largely as a DH, but eventually had a great deal of playing time in left and right field, and was part of the ’87 World Champs when he drove in 46 runs in 122 games.

He was a career .251 hitter, but in 1991, as a seasoned veteran, he posted career bests in batting average, on-base percentage and slugging (.303/.401/.485). His walk to strikeout ratio was the best figure he ever achieved (1:1.04).

And despite playing in only 93 games, he led the league in pinch-hits (13) and tied an AL record with seven consecutive pinch-hits.

Next. Forgotten stars of the NL Central. dark

After his retirement as a player, Bush managed to find himself another MLB position that he has hung onto as well. Since late in 2006, he has been an assistant general manager with the Chicago Cubs in charge of scouting.