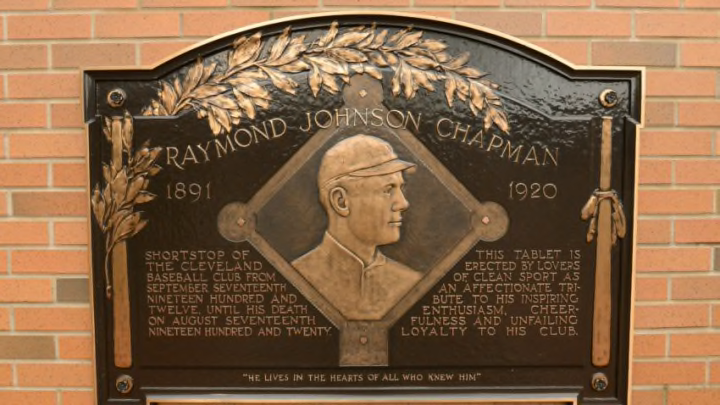

Sunday marks the centennial of the majors’ only on-field fatality, as Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman was killed by a pitch.

One hundred years ago today, at the historic Polo Grounds in New York, baseball’s greatest tragedy unfolded. Ray Chapman, shortstop for the soon-to-be World Series winning Cleveland Indians, was fatally beaned by New York Yankee pitcher Carl Mays. Chapman, who was struck in the temple by a Mays fastball, was taken to a nearby hospital where he died early the following morning.

A century later, he remains the only major league player ever to die as the direct result of an on-field injury.

Chapman was a 29-year-old shortstop and team leader on the Indians, who entered that Monday’s game against Mays’ New York Yankees part of an intense three-way pennant race. The Indians were locked in a virtual tie for first place with the Chicago White Sox, both of them one-half game ahead of the Yankees.

He was in his accustomed second spot in the batting order when he came up to face Mays leading off the fifth inning with Cleveland leading 3-0. Chapman, batting .303 at the time, was officially zero-for-one on the day, having sacrificed in the first inning and grounded into a double play in the third.

In that era, of course, players did not wear any sort of head protection beyond their standard caps. Nor, in those days, were balls removed from play unless they became soft or misshapen. There is a sense that several innings of use had rendered the fatal ball dark and difficult to see.

Mays’ first pitch was a high-tight fastball that Chapman – who had a reputation for leaning out over the plate – failed to react to. The ball struck him squarely in the head, bouncing back onto the field of play with a crack so loud that some Yankee players initially reacted as though the ball had been hit. In fact, he had suffered a skull fracture.

Teammates helped him to the visiting team’s center field locker room area, from where a physician on the scene ordered him transferred to St. Lawrence Hospital, about a half mile away.

Surgery to ease pressure on his brain was performed there, but the post-operative wait soon became a death watch. His manager, Tris Speaker, announced Chapman’s death the following morning. “Ray Chapman was the best friend I ever had,” a worn and emotionally drained Speaker said. “I would willingly abandon all hope for the championship …if by doing so I could recall my teammate and best friend to life.”

Mays, already widely suspected of being willing to throw at a player’s head, was vilified most everywhere. An unsigned article by the St. Louis Browns correspondent in the next edition of the Sporting News was typical. “If the news had come over the wire that a player had been killed by a pitched ball without naming who pitched the ball, the Browns to a man would have guessed,” it said.

More from Call to the Pen

- Philadelphia Phillies, ready for a stretch run, bomb St. Louis Cardinals

- Philadelphia Phillies: The 4 players on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore

- Boston Red Sox fans should be upset over Mookie Betts’ comment

- Analyzing the Boston Red Sox trade for Dave Henderson and Spike Owen

- 2023 MLB postseason likely to have a strange look without Yankees, Red Sox, Cardinals

The exception was in New York itself, where commentators rose to Mays’ defense. W.O. McGeehan, writing in the New York Tribune, demanded to know why so many believed Mays should be banned from baseball. “The player’s conscience is clear with regard to the accident,” he wrote.

For several days Mays voluntarily isolated himself from the park while the Indians and much of the rest of the league mourned Chapman. But he returned to the mound exactly one week after the incident, pitching a 10-0 shutout victory over the Detroit Tigers. By then the White Sox had taken a two-game lead over the despondent and listless Indians.

But Speaker rallied his team over the season’s final month, eventually finishing two games ahead of the White Sox with New York one game further behind.

The Chapman death is one of three reasons why that 1920 pennant race is today considered among the most important – and perhaps the most important – in baseball history.

The second reason was the late-season exposure of the previous fall’s Black Sox scandal, in which eight members of the Chicago team conspired with gamblers to fix the World Series. A Chicago grand jury exposed that scandal in September, precisely during the final 10 days of the tightly contested race.

In fact on Sept. 24, 1920 – the very day the names of the suspect players were leaked from the grand jury room – the Sox and Indians were playing a pivotal game in Cleveland on which the outcome of the pennant race might be said to have ultimately hinged.

The Indians won that game 2-0. Chapman’s replacement at shortstop, rookie Joe Sewell, had two hits and scored a run. A few days later, Sox owner Charles Comiskey announced the suspensions of the seven suspects who remained on the roster, effectively gutting his team.

The Indians went on to defeat the Brooklyn Dodgers in that fall’s World Series. They wore black armbands in memory of Chapman.

The third reason why the 1920 pennant race is today considered so transcendent? It was Babe Ruth, who in his first season with the New York Yankees hit 54 home runs and changed the way the game is played.