Due to COVID-19, the 2020 induction ceremony at the Baseball Hall of Fame was postponed. That may be the only reason there will be inductees in 2021.

With the Hall of Fame induction ceremony set for July 25, there is a legitimate chance the only new members entering baseball’s ultimate shrine will have been chosen last year.

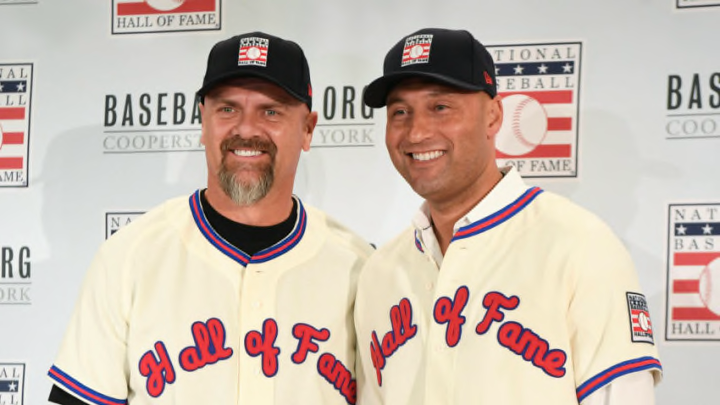

COVID-19 delayed the induction of the 2020 honorees — former New York Yankees shortstop Derek Jeter; the late Marvin Miller, longtime executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association; former All-Star catcher Ted Simmons; and former National League MVP outfielder Larry Walker.

But the coronavirus pandemic also made it not feasible for for the Early Baseball or Golden Days committees to meet to consider players from 1871-1949 and 1950-69, respectively. So there will be no Veterans Committee selections in 2021.

As for the 25 players on the Baseball Writers Association of America’s ballot? It is a problematic group, at best, and some of the more controversial nominees are running out of time.

Per Baseball-Reference.com, Curt Schilling received 70 percent of the vote in 2020, 5 percent short of the necessary 75.0 percent for induction. Roger Clemens was next at 61 percent, Barry Bonds polled at 60.7 percent and Omar Vizquel was the only other player named on at least half of the ballots at 52.6 percent.

With all due respect to the 11 players selected as first-time nominees in 2021, there almost certainly not be anyone chosen in the first year of eligibility. Not from a group that includes Mark Buehrle, A.J. Burnett, Michael Cuddyer, Dan Haren, LaTroy Hawkins, Tim Hudson, Torii Hunter, Aramis Ramirez, Nick Swisher, Shane Victorino and Barry Zito.

This is the next-to-last year on the ballot for Bonds, Clemens and Schilling, with the time on the ballot being reduced to 10 years for the 2015 voting year. That was an obvious nod to getting the Steroid Era players off the list more quickly than the 15-year eligibility period that had been the standard before that.

Schilling has the least amount of ground to make up to gain entry into the Baseball Hall of Fame, but his case has been hampered over the years for several reasons, both baseball- and non-baseball-related.

Critics can point to Schilling’s lack of hardware — he never won a Cy Young Award, though he did finish second three times. He shared a World Series MVP award with Hall of Famer and Arizona Diamondbacks teammate Randy Johnson in 2001 and was NLCS MVP in 1993 while helping the Philadelphia Phillies to a surprise World Series berth.

His postseason resume is almost unassailable — 11-2 in 19 postseason starts with a 2.23 ERA and 0.968 WHIP over 133.1 innings to go with 120 strikeouts and only 25 walks. Throw in the “bloody sock” game as the Boston Red Sox roared back from a 3-0 deficit to win the 2004 ALCS and he’s pretty much locked in as an October legend.

But Schilling’s off-the-field behavior has — fairly or not — turned off many voters. Schilling is active in Republican politics and most recently was at the center of some controversy over comments he made on social media about the Jan. 6 events at the Capitol Building in Washington, per azcentral.com.

Schilling was fired from his role as a baseball analyst at ESPN over an social media post in 2016 on the topic of transgender bathroom laws.

The cases against Bonds and Clemens are much more clearly defined. Taken just in the context of their on-field accomplishments, one could argue Clemens is the greatest right-handed pitcher in baseball history and that Bonds is the sport’s greatest hitter.

But that would ignore the elephant that has been in the room since each player first appeared on the Baseball Hall of Fame ballot in 2013. Bonds’ numbers have trended up from a low of 34.6 percent in his second year of eligibility (he got 36.2 percent the first time around) to a high of 60.7 last year.

On the field? Bonds was named MVP a record seven times, took home eight Gold Gloves, won two batting titles and, oh by the way, clubbed a record 762 home runs to go with all-time marks of 688 intentional walks and 2,558 walks overall.

Clemens’ voting history matches that of Bonds, only at slightly higher percentages — a low of 35.4 percent in 2014 after being named on 37.6 percent of ballots the previous year and peaking with his 61.0 percent mark in 2020.

Clemens holds no all-time marks — the guys who threw 400 innings a year back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries swallowed up a lot of those lines in the record book — but won 354 games, trailing only Warren Spahn (363) and Greg Maddux (354) in the live-ball era (since 1920), according to Stathead.com.

He is also third on the all-time strikeout list, one of just four pitchers with more than 4,000 strikeouts. The others are pretty good company: Nolan Ryan, the aforementioned Johnson and Steve Carlton — all members of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Other players from that era have been able to overcome the steroid stigma — whether it was deserved or not — to gain induction, such as Mike Piazza and Jeff Bagwell.

Vizquel, on the other hand, is attempting to become one of the few players elected to the Hall of Fame more for his defensive prowess. But shortstop is the right position to try and pull that off with predecessors such as Luis Aparicio and Ozzie Smith.

Vizquel wasn’t without worth on offense. He was a career .272/.336/.352 hitter in 2,968 games and stole 404 bases to go with 1,445 runs scored. Vizquel also walked (1,028) almost as often as he struck out (1,087), so he didn’t add a lot of empty outs to the batting order.

The top line on his Baseball Hall of Fame resume, though, is the one about his 11 Gold Gloves, second only to Smith’s 13 all-time (while bearing in mind the Gold Glove wasn’t awarded until 1957.

If no one is elected by the BBWAA this year, it would mark the second time in less than 10 years that has happened. It also happened in 2013. Previously, no players received enough votes for enshrinement in 1945, 1946, 1950, 1958, 1960 and 1971.

Given how political the BBWAA voting process has become over the years — blank protest ballots and voters who can’t wait to get on the talk-show circuit to blather on about why they voted the way they did — the system is still quite messy. That messiness might be enough to prevent anyone from achieving the 75 percent of the ballots needed to join Jeter and company in July.