Hank Aaron combined consistency and brilliance in Hall of Fame career

Former Major League Baseball home run king Hank Aaron died Friday morning at the age of 86.

CBS-46 in Atlanta first reported the news of Aaron’s passing.

Aaron played for the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves from 1954-74 before returning to where his big-league career started with the Milwaukee Brewers for his final two seasons. Two of his all-time career records still stand: his 2,297 career RBI as well as his total of 6,856 total bases.

For more than 30 years, Aaron’s 755 career home runs stood atop baseball’s leader board, with the Hall of Famer passing the legendary Babe Ruth with his 715th career home run against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974.

That record fell when Barry Bonds hit career home run No. 756 on Aug. 7, 2007, a record for which legitimacy has been questioned because of allegations Bonds used performance-enhancing drugs.

I was 7 years old the night Aaron hit No. 715 off Dodgers left-hander Al Downing and the memories are still vivid. It’s part of what made me fall in love with the game in the first place, even if I didn’t understand until I was older the obstacles and the hatred Aaron had to overcome in chasing down Ruth’s record.

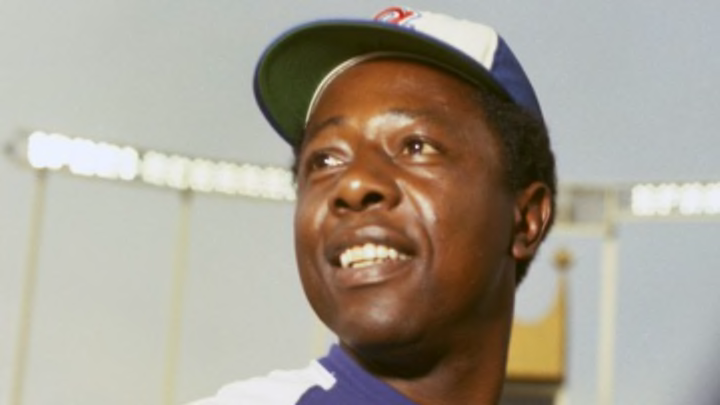

At first glance, Hank Aaron was a normal guy — 6-feet, 180 pounds, nothing to indicate he would launch more baseballs over fences than anyone who ever played the game.

And his swing was just so easy, just a flick of the wrists and the bat ripped through the hitting zone. No wasted motion, no exaggerated launch angles, no swing for the downs mentality.

In hitting 755 career home runs, Aaron never struck out more than 97 times in a season. While he never threatened Ruth’s single-season record of 60 home runs or Roger Maris’ later mark of 61, Aaron hit at least 20 home runs for 20 straight seasons, from his second season in 1955 through his 21st season in 1974.

Looking for consistency? Hank Aaron was your guy.

Consider this for a moment — a slash line of .305/.374/.555, an OPS of .928 and an OPS+ of 155 to go with 31 doubles, five triples, 37 home runs, 107 runs scored and 113 RBI.

That’s a pretty damn good season right there.

That was Hank Aaron’s average per 162 games for his 23-year career. You know, just an average, run-of-the-mill, ho-hum campaign.

Along with Thurman Munson — I grew up a New York Yankees fan and played catcher because it was the one position where a tiny kid could play regularly, because no one else wanted to be back there — Aaron was one of my first baseball heroes.

He helped launch a lifelong love affair with the game that has persevered through player strikes, lockouts, scandals and the ways the sport has evolved over those intervening 40-plus years.

I never got a chance to meet Hank Aaron. If I had, I would have thanked him for helping to lead me to baseball and showing me that you didn’t have to be some sort of super-athletic specimen to be a great player. That latter lesson still resonates with me — show up for work every day, do the job and good things will generally happen.

Henry Louis Aaron was born Feb. 5, 1934, in Mobile, Ala., and was raised there, starring in football and baseball at Mobile’s Central High School as a freshman and sophomore before transferring to the Josephine Allen Institute for his final two years of high school, according to a biography written by Bill Johnson on the Society for American Baseball Research‘s website.

Aaron’s first exposure to professional baseball was signing for $200 per month with the Indianapolis Clowns, champions of the Negro American League at the time. In 26 games for the Clowns in 1952, Aaron hit .366 with five home runs and nine stolen bases.

That led to a contract from the Boston Braves in June 1952 and his move to the Eau Claire Bears, a Class-C club in the now-defunct Northern League. In 1953, he advanced to the Jacksonville Braves in the Class-A South Atlantic League.

Another player’s bad break led to Aaron getting his first shot at the big leagues and he maximized it, earning the regular left field job for the now-Milwaukee Braves after Bobby Thomson broke his ankle during spring training.

His season was cut short by a broken ankle of his own, but he was on his way. In 1955, the Braves shifted Aaron to right field, where he stayed for most of the next 16 seasons — save for a couple of years when he was used in center field — before a transition to first base in the early 1970s.

Again, it was his remarkable consistency that was the hallmark of his long career. He was more than just a slugger, he was a pure hitter. He had more than 3,000 hits that weren’t home runs, walked more times than he struck out (1,402 to 1,383) and, oh by the way, stole 240 bases, capped by a 44-homer, 31-steal season in 1963.

Aaron’s career-high in home runs was the 47 he hit in 1971. He led the National League in home runs four times (1971 was not one of those seasons) and also topped the NL in RBI in four different seasons. The testimonial for his well-rounded approach at the plate was leading the league in total bases eight times and leading the league in hits and doubles twice each.

And he had to fight through vicious hate mail and threat — not just against himself, but also his children. Given the events of the last year, it’s not hard to extrapolate how difficult it had to be at a time that was less than 10 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act and not yet 20 since Rosa Parks famously refused to go to the back of the bus.

Aaron retired after the 1976 season, one shortened by just the second major injury of his career (an injured knee), and was elected to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 1982, even though nine voters made the decision that the all-time leader in home runs and RBI wasn’t worthy of enshrinement the first time around.

He returned to the Braves organization as vice president of player development while also branching out into the automobile and restaurant industries.

In 1997, his hometown Mobile Bay Bears opened Hank Aaron Stadium and in 1999, MLB began presenting the Hank Aaron Award to the top offensive player in each league.

And despite the controversy swirling around Bonds’ run at the all-time home run record, Aaron responded with grace and dignity, appearing in a recorded message on the giant scoreboard at what was then known at AT&T Park.

The accomplishments of Henry Aaron in baseball could go on for hours — nearly 3,300 games played, 25 All-Star selections, a World Series title over the Casey Stengel-era Yankees to name just a few — but it was the attitude he brought to the game that made him special.

He didn’t have the flash of contemporary rival Willie Mays. Instead, he showed up to work every day, took the job seriously and was amazingly consistent for longer than anyone would ever be expected to be.

Henry Aaron was an original and his death leaves a huge hole in baseball.