MLB history: The first Black Latino

Black Americans were not the only group liberated from the game’s sociological restrictions by Jackie Robinson’s arrival. The same unofficial rules had prevented dark-skinned Latinos from playing, although their lighter-skinned cousins had been deemed acceptable for decades.

That changed with Veeck’s signing of Orestes ‘Minnie’ Minoso to a Cleveland Indians contract prior to the 1949 season. A three-year member of the Negro League’s New York Cubans, the native of Cuba took longer to develop. Batting only .181 in just 20 at bats for Cleveland, he was shipped to the Chicago White Sox in 1951.

But as the first dark-skinned player to appear on the field in the nation’s second largest city, Minoso thrived in Chicago. He batted .324 for the Sox, finished second in Rookie of the Year voting and fourth in the MVP race and solidified what would become a 17-season career as an outfielder.

Minoso, who died in 2015, is the only true pioneer of the integration movement not yet enshrined in Cooperstown, although he still draws support when the appropriate veterans committee meets to consider figures from his era.

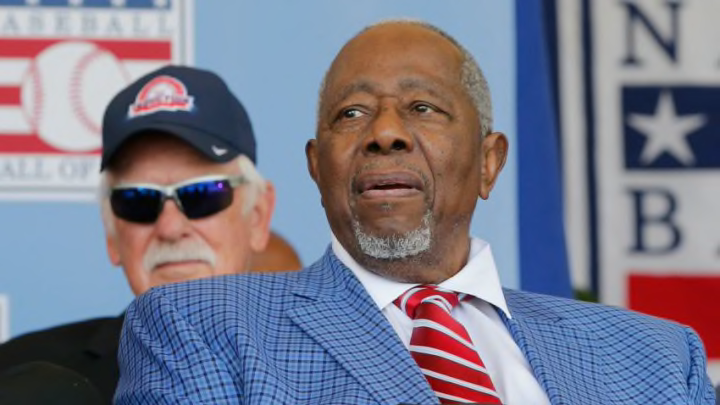

With Hank Thompson, Monte Irvin co-integrated the New York Giants in July 1949. His arrival was in part occasioned by the success Robinson, Campanella and pitcher Don Newcombe were by that time having across town in Brooklyn.

A long-time veteran star with Newark of the Negro National League, Irvin had hit .370 in 1946 when Newark won the pennant and .300 in 1947.

Already 30 when he debuted, Irvin played eight seasons for the Giants and had a role in both their 1951 and 1954 pennants. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1973 largely for his Negro League play.