In sports, any proactive team seeks to find advantages within (and sometimes outside of) the rules of the game. Teams like the Oakland Athletics and Boston Red Sox of the early 2000s found success by exploiting league-wide inefficiencies in evaluating players. It wasn’t long before the rest of the league caught up and the era of advanced data analytics was born in baseball.

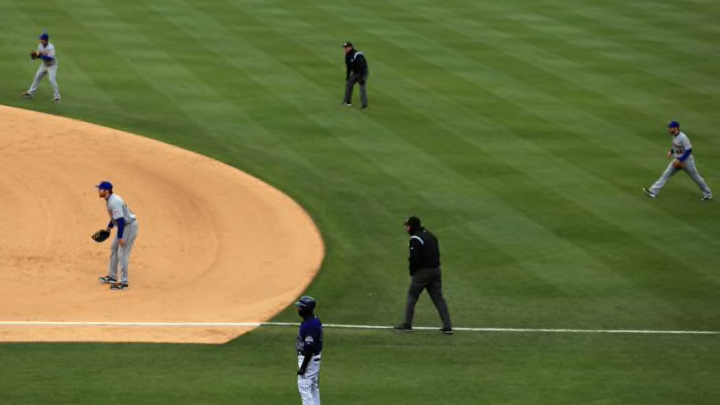

Recently, we’ve seen a resurgence of defensive shifts in Major League Baseball and increasing numbers of calls to limit or even eliminate shifts.

The modern-day baseball game now has some sort of shift for nearly one out of every three batters, more than double the number of just five years ago. For some teams, the shift has become the majority of what they do as both the Dodgers and the Mets utilized a shift on more than half of their opponents’ plate appearances in 2021.

Baseball has seen many rule changes over the years. Baseball Almanac has a list of such changes. The most celebrated change of recent baseball history was the lowering of the mound following the 1968 season from 15 inches to 10 inches. This was a result of the historically low offensive output of previous seasons. Interestingly enough, that same offseason, the strike zone was returned to the smaller zone that had been in use through 1961. It would seem to me that more balls and fewer strikes would have much more to do with the increase in offense but we’ll never truly know. George Resor did a more in-depth look at this back in 2014 for The Hardball Times.

And so, in 2022, there is a call from some for a change in the rules to limit shifts. A quick Google search will find numerous articles calling for the end of the shift, often citing low offensive output as their reasoning. In recent years, several players have called for some limitations. Joey Gallo was quoted in a recent article by Jayson Stark at the Athletic as saying, “I think at some point, you have to fix the game a little bit. I mean, I don’t understand how I’m supposed to hit a double or triple when I have six guys standing in the outfield.”