Grade: B+

Giving AL Cy Young voters credit for handing the Cy Young Award to Justin Verlander feels a bit like handing out grades of A on a math test where 90 percent of the questions were “how much is 2 + 2?”

Obviously, Verlander deserved the award. He led the AL with 18 wins against just four losses, he also led with a 1.75 ERA and his 220 ERA+ even made Sabermetricians smile…to the extent they do that sort of thing.

If you wanted to find a dent in the Verlander armor, you could do so…but you’d be seen as argumentative. Let’s do so just for the fun of it. At 5.9, he only tied Alex Manoah for third in pitching WAR, behind Dylan Cease (6.4) and Shohei Ohtani (6.2). Verlander’s WAR total lagged due to his ordinary workload: he turned in just 175 innings, 26 fewer than teammate Framber Valdez, who led the league.

Was there a case for Cease, who finished second in the overall voting? Well, his own workload (184 innings) wasn’t exactly taxing; he ranked 10th in the league in that category. He did finish second to Verlander in ERA, but it was a distant second, at 2.20, nearly a half point behind the winner’s 1.75.

To fall back on comparisons again, the margin distancing Verlander from Cease in ERA was greater than the margin separating Cease from Tampa’s Shane McClanahan in fifth place.

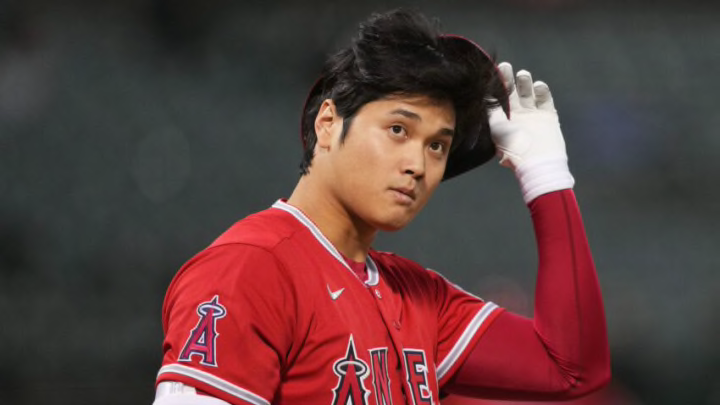

The selection of Manoah as a finalist ahead of Ohtani was a marginal call. Ohtani (6.2 to 5.9) had the slightly higher WAR, and of their ERAs (2.24 for Manoah, 2.33 for Ohtani) there was little to choose. Manoah’s principal advantage, then, lay back in that old standard, workload. He completed 196.1 innings on the mound, Ohtani stopped at 166. Showing up is a beautiful thing, although in fairness to Ohtani, he was otherwise occupied.

We’ll save that part of the argument for consideration of the MVP vote.

Grade: D

You could make an argument that the most valuable player in the National League was not even nominated for Most Valuable Player in the National League.

We’re talking here about Sandy Alcantara, the unanimous Cy Young Award choice. The case for Alcantara as MVP is not at all clear-cut, the case for his consideration as a finalist most definitely is.

Here’s that case. At 8.0, he had the league’s best WAR. He also delivered the highest Win Probability Added, at 5.4. The WAR calculation was close enough to be gray; Nolan Arenado came in at 7.9, just a tick behind Alcantara. But the WPA score was not close; Alcantara beat the runner-up, Paul Goldschmidt, by more than half a game (5.4 to 4.7).

By other measures, the contest is closer. Batters hit 33 percentage points below the league average against Alcantara…but the three finalists (Arenado, Goldschmidt, and Manny Machado) all beat the league average by at least 50 points, 74 in the case of Goldschmidt, the batting champion.

The same was true of the other slash line elements. Alcantara over-performed the league average in restricting opponents on base average by 51 percentage points. But Goldschmidt over-performed the league average by 70 points and Machado by 52. (Arenado only beat the league average by 44 points.

Alcantara held opponents 76 points under the league slugging average. But all three of the finalists over-performed that average by a minimum of 135 points (in the case of Arenado) and as much as 180 (in the case of Goldschmidt).

With 886 batter-pitcher confrontations during the season, Alcantara was also a much more consistent presence in determining game outcomes than any of the finalists, of whom Goldschmidt (651) had the most. That’s 36 percent more batter-pitcher outcomes than the highest of the actual finalists.

None of these numbers produce a clear MVP choice, but they all confirm that Alcantara at least should have been solidly in the mix. Just to pick on Machado, Alcantara beat him in WAR, WPA, and Base-Out Runs Saved, another measure of contribution to victory.

Instead, voters made the Marlins pitcher a forgotten 10th, with only three of 30 voters even including him among their top five. His vote total was about one-tenth that of Goldschmidt.

Why wasn’t Alcantara given stronger consideration? The answers, silly as they seem, are obvious. First, he’s a pitcher, and MVP voters blatantly discriminate against pitchers. It’s their nature. Among 19 players who got at least one MVP vote, only four were pitchers.

Second, he played for a losing team. In the eyes of most voters, Alcantara couldn’t be Most Valuable because Jacob Stallings, Miguel Rojas, and Avisail Garcia stunk.

That’s not much of an argument, but it’s all the voters have.