Adjusted for inflation, buying power isn’t what it used to be in MLB

Considering inflation, which MLB player had or will have more value: Babe Ruth in the early 1920s or Codi Heuer today?

Silly question, right? In the early 1920s, the Babe was busy redefining how the entire game was played. In 1921, he hit 59 home runs, a total that was more than hit by five American League teams.

Between 1920 and 1924, he led the AL in home runs, RBI, runs scored and on base average four times each, and in slugging average every year. For those days, he was paid like it too. In 1922, he signed a new contract with the Yankees making him the first player in history to receive the astonishing sum of $50,000.

Looking strictly at his record, Heuer pales by comparison. In part-time work across two seasons, he’s made 86 relief appearances covering fewer than 100 innings with a 3.56 career ERA.

For his full professional life, Heuer has generated just 1.4 WAR with just 2.7 Win Probability Added. Not surprisingly, then he will make only a few bucks over the major league minimum, $750,000, to pitch out of the Chicago Cubs’ bullpen in 2023.

The Babe only needed eight weeks between July 26 and September 22, 1922 to generate as much WPA as Heuer has produced for his career to date. And except for that record-breaking $50,000 contract, 1922 was one of Ruth’s few bad seasons.

Money, however, is the one area where a non-descript contemporary reliever such as Heuer can stand toe-to-toe with the Babe. Because, you see, adjusted for inflation, the record $50,000 contract Ruth played for in 1922 works out to just $762,000 in today’s economy. Financially, then, that makes Heuer (and virtually every other player not working for the $720,000 minimum) the Babe’s equal.

Value, obviously, has been an adjustable commodity in MLB since the days of Babe Ruth.

This winter’s mega-signings of such players as Aaron Judge, Carlos Correa, Xander Bogaerts and Jacob deGrom to contracts well into nine figures has planted the concept that the game has entered a new era of hyper inflation.

The reality is not quite so simple. The fact is that measured on an annualized basis values really began hyper-increasing a quarter-century ago. What’s driving the larger dollar amounts today isn’t inflation or the annual value but the numbers of years added on to recent contracts: nine years for Judge, 11 years for Bogaerts, and 14 years for Fernando Tatis Jr.

From $50k to $100k

When Hank Greenberg died in 1986, numerous news sources eulogized him as the game’s first $100,000 player. It was written that Greenberg got that much from the Pittsburgh Pirates after they purchased him from Detroit prior to the 1947 season.

You can still find internet sources today who assert that Greenberg was the first to $100,000.

Our best understanding of the facts suggest otherwise. They say Greenberg only actually got about $85,000 from the Pirates, and that the $100,000 barrier lasted two more seasons until being broken by Joe DiMaggio in 1949.

By 1949 standards, DiMaggio’s six-figure deal sounds rewarding. Again, however, adjusted for inflation, it looks puny by modern standards.

It adjusts to $1.25 million in today’s currency. Who today will earn about $1.25 million? That happens to be precisely the amount for which Austin Gomber will labor to get opponents out in Colorado.

Is Austin Gomber the modern equivalent of Joe DiMaggio? On the field, not hardly. Gomber was 5-7 with a 5.56 ERA in 17 starts for the Rockies in 2022. That equated to a 0.3 WAR. DiMaggio amassed a 4.3 WAR in helping the Yankees to the 1949 World Series title. Inflation can’t explain that difference.

Best case scenario: That’s something for Gomber to shoot for in 2023 … but you probably don’t want to bet on it.

Free agency, then $500k

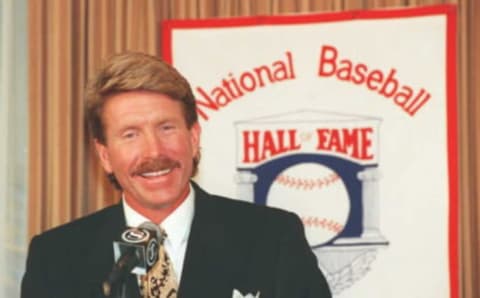

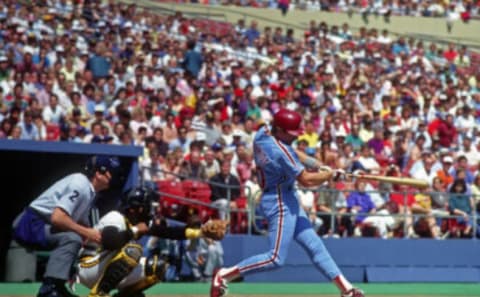

Another 30 seasons elapsed before the game’s top salary hit the next landmark figure, $500,000. The player who got that award was Mike Schmidt, slugging third baseman of the Philadelphia Phillies.

The arrival of free agency certainly spurred the pay increases. Precise data for the 1950s and 1960s is scattered, but we believe, for example, that Mickey Mantle topped out at $100,000 (which he first earned in 1963) that Ted Williams never made more than $90,000 (1950) and that Reggie Jackson earned $135,000 in 1974, the year after he won the MVP Award.

Catfish Hunter became the first modern “free agent” when he successfully argued that A’s owner Charles Finley had violated the terms of his contract following the 1974 season. Hunter signed with the Yankees for $3.2 million over five years — essentially $640,000 per season. One year later, an arbitrator invalidated the owners’ interpretation of the reserve clause, legitimizing free agency for all players with expired contracts.

The Phillies reacted to the development more assertively than many teams. One of their first steps was to secure their own best player. Prior to the 1977 season they offered Schmidt $2.8 million over five years (that’s $560,000 per year) and he took it.

By modern standards, though, even Schmidt’s half-million dollar deal doesn’t look all that impressive. Adjusted for inflation, that only works out to $2.39 million today. What other player will make $2.39 million in 2023?

New Pirates reliever Jarlin Garcia, for one. This winter Garcia signed a two-year deal with the Pirates that will pay him $2.5 million in 2023, increasing to $3.25 million in 2024.

What did Garcia do to earn Schmidt-level money? In six seasons, he’s 17-15 with a 3.61 ERA across 285 appearances encompassing 322 innings of work, about 50 innings per season.

The $1 million plateau

There is some dispute about which player signed the first $1 million per season contract. Some say Pittsburgh’s Dave Parker did so when he signed a five-year, $5 million deal with the Pirates. But the deal was incentive-laden, and Parker never actually earned $1 million in any of his five seasons playing on that contract.

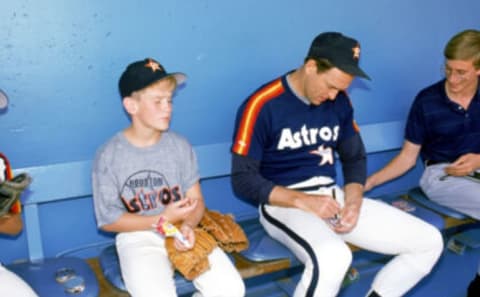

Thus the distinction falls to Nolan Ryan who, following the 1979 season, became a free agent. Ryan signed with the Houston Astros, who paid him $4.5 million over four seasons. He earned $1.125 million in 1980, the contract’s first year. The best available sources indicate that Parker actually earned $775,000 in both 1979 and 1980.

But even Ryan’s breakthrough of the $1 million milestone doesn’t mark the beginning of the acceleration of player salaries. Adjusted for inflation, that $1 million equates to only $3.74 million today.

Who else will earn $3.74 million for playing major league baseball in 2023? Among others, San Diego reliever Luis Garcia ($3.75 million). Garcia earns that on the basis of a 10-season career in various teams’ bullpens, during which he has a 19-24 record, a 4.05 ERA, 11 saves and 424 appearances covering 409 innings of work.

Garcia signed a two-year deal with San Diego in December of 2021. He was 4-6 with a 3.39 ERA and 3 saves in 64 appearances (61 innings) last season. Obviously we have not yet arrived at Nolan Ryan standards.

Four years, $2 million

The honor of being the game’s first $2 million player is disputed. Some, notably Baseball Almanac, say it was George Foster when he signed a five-year deal with the Mets in February of 1982. But other sources assert that Foster did not clear the $2 million mark until 1986, when his pay was $2.8 million.

Others say the first $2 million player was Dave Winfield, who in 1980 signed a 10-year deal with George Steinbrenner’s Yankees. But the terms of that deal have always been in dispute, including between Steinbrenner and Winfield, who eventually sued the Yankee owner. The best evidence is that Winfield never actually topped $2 million during his decade-long Yankee stay.

Michael Haupert, a SABR researcher, settles on Mike Schmidt as the first to actually earn $2 million. But even that is in dispute: Haupert says Schmidt broker the barrier in 1986, but Baseball Reference says Schmidt also earned $2.023 million as early as 1984.

Lacking consensus, the best evidence points to Schmidt in 1984.

Schmidt’s $2 million earnings for 1984 translates to about $5.44 million in current money when adjusted for inflation. That’s comparable to the $5.5 million the Boston Red Sox will pay Alex Verdugo to play right field for them in 2023.

In his third season as a Red Sox regular, Verdugo batted .280 with 11 home runs and 74 RBI in 2022. He generated 1.2 WAR and had a 102 OPS+, 1000 representing major league average.

Not that it’s necessarily a fair comparison, but in 1984 Schmidt generated 7 WAR and had a 155 OPS+ on the way to earning that $2 million.

From a performance standpoint, that represents deflation, not inflation.

Again at the $5 million standard, there is debate over who got there first. Some sources contend it was Roger Clemens, who prior to the 1991 seasons signed a five-year contract with the Red Sox that included raises surpassing $5 million.

But Clemens didn’t actually earn $5 million in a single season until late in that contract. By then, Bobby Bonilla’s free agent contract with the Mets ensured that Bonilla would break the $5 million barrier in 1992. So the correct answer is Bonilla.

Bonilla was a four-time All-Star and centerpiece of a Pirates team that had won the NL East in 1990 and 1991 when he cashed in. Coming off a season in which he batted .302 with 44 doubles and 100 RBI and finished third in the MVP voting, Bonilla’s unprecedented value on the open market was no surprise.

The problem was that the Mets never really got the Bonilla they thought they were buying. In New York, he averaged just .270, his RBI totals dipped into the 70s, and as his performance declined he became a clubhouse distraction with assistance from the New York media.

By the middle of 1995, Bonilla was enough of a problem that the Mets abandoned traded him and the contract’s final year and a half to Baltimore for a couple of players who never did anything.

The $5.3 million Bonilla received in 1992 adjusts for inflation to about $10.4 million in today’s terms. Who else is a $10.4 million player today? Steven Matz.

After Matz posted the best season of his career, going 14-7 with a 3.82 ERA for Toronto in 2021, the Cardinals signed him to a four-year deal with escalating salaries. Matz received $8.5 million for pitching with St. Louis in 2022, he will get $10.5 million in 2023, rising to $12.5 million in 2024 and 2025.

For that investment, Matz gave the Cardinals a 5-3 record in 15 appearances, 10 of them starts, in 2022. But he was lucky; both Matz’s ballooning 5.25 ERA and his depressed 73 ERA+ — on a scale where 100 equals the major league average — defy the favorable record.

The Cardinals appear to be questioning their own wisdom in the Matz deal. Their own depth chart does not project him among the five best rotation options for 2023, and also does not project him as a bullpen regular.

For the moment, then, he is a $5 million player without a purpose.

The first to $10 million

With the end of the 1994-95 strike, salaries began to escalate at a previously unseen pace. In a few years that pace would bring player values to a level matching — and in some cases surpassing — current standards when inflation is factored in.

Only five seasons were required for the game’s top earner to double Bonilla’s $5 million salary of 1992. That barrier-breaker was slugger Albert Belle, who in 1997 hit free agency following several stunning years with the Cleveland Indians.

Belle was the AL RBI leader three times between 1993 and 1996, leading the league in home runs with an even 50 in 1995. He finished second in that year’s MVP voting and was a principal reason why the Indians won 100 of their 144 games and went to the World Series.

His value on the open market came as no surprise, the White Sox offering the precedent-setting two-year, $20 million contract.

Belle had two good seasons in Chicago, averaging .301 with nearly 40 home runs and 134 RBI. But it turned out that the Sox needed more than just Belle; they finished a distant second to Belle’s old team, the Indians, both seasons.

The $10 million Belle earned from Chicago in 1997 adjusts to $17.29 million by today’s standards, and for the first time that adjustment produces players who — considering inflation — begin to justify by performance their earning power. The closest financial comp in the current game is Yankee first baseman Anthony Rizzo, who will make $17 million in the second season of a four-year deal.

Rizzo’s 2022 average was a disappointing .222, but he did deliver power in the form of 32 home runs and an .817 OPS. At age 32, he also remains a more-than-competent first baseman.

The $15 million pitcher

It did not take long for the $15 million mark to follow the $10 million mark in falling. A short two seasons after Belle got that $10 million-per-year deal from the White Sox, the Los Angeles Dodgers went looking for an ace for their pitching staff.

They found him in Kevin Brown, coming off consecutive seasons in which he had taken first the Florida Marlins and then the San Diego Padres to the World Series. The Dodgers offered six years at $15.7 million per year and Brown signed.

Brown won 58 games against just 32 losses for Los Angeles, and his 2.83 ERA improved on his career 3.28 mark, so it would be unfair to assert that he was a disappointment. But the Dodgers never managed to win their division with Brown heading their rotation, so in December of 2003 they traded Brown’s final two seasons to the Yankees.

Adjusted for inflation, the $15 million Browne earned in 1999 — which translates to $24.95 million by today’s standards — will buy you a lot of pitcher. Or not.

The Washington Nationals got both the good and bad when they gave Patrick Corbin a six-year, $140 million deal prior to the 2019 season.

Corbin went 14-7 in 33 starts for Washington during their World Series run of 2019. That included a Game 7 victory in which Corbin delivered three vital bridge innings between starter Max Scherzer and closer Daniel Hudson.

So if you ascribe to the theory that any contract which brings a world championship is a good one, the Corbin deal has already paid off.

The story since 2019, of course, has been different. Corbin led the NL in losses in both 2021 and 2022, and his ERA has ballooned alarmingly, from 3.25 to 4.66 to 5.82 to 6.31.

But since Corbin will earn $24.4 million in 2023, the Nats have no viable option other than hoping for a performance turnaround, which is why their projected rotation pegs Corbin as the team’s No. 2 ace behind Strasburg.

The $20 million+ stratosphere

This discussion begins with not one landmark but two. Adjusted for inflation, the $20 million threshold — first reached in 2001 — equates to $37 million in today’s market.

In a sense, that $20 million threshold was first broken by Manny Ramirez, who in December of 2000 signed a massive 10-year deal with Boston that would direct $20 million his way as quickly as its third season.

Bu the first to actually cash a $20 million check was Alex Rodriguez, who beat Ramirez to that level by two years. In January of 2001, Rodriguez signed his famous 10-year, $252 million contract with the Texas Rangers, delivering $22 million A-Rod’s way in the first year (2001).

The Rangers only tolerated the enormity of that deal for three years before shipping the remainder of it to the Yankees, where Rodriguez finished his career.

When we are talking about $37 million, even in the modern game, the comparisons are limited to the financial elite. Only 15 players will earn even $30 million in 2023, and only eight will top $35 million.

Financially, the closest comp to what Rodriguez got in 2001 turns out to be exactly the player you’d probably first guess. That would be Mike Trout, who will get $37.116 million to play centerfield for the Angels.

And beyond…

Since the $20 million threshold was crossed in 2001, baseball salaries haven’t really kept up with inflation, at least not when annualized at the top end.

Rodriguez was also the first to earn $25 million, that happening when he opted out of what was left of his Texas deal and signed a new contract with the Yankees starting in 2008. It paid him an even $28 million.

That $28 million in 2008 cash equates to $38.7 million today. Only four players will earn in that stratosphere in 2023, the closest to Rodriguez being Anthony Rendon, at an even $38 million.

The $30 million barrier first fell in 2015, and Trout was the one who broke it. He signed with the Angels for $144.5 million spread over six seasons, including $34.1 million in 2018. Adjusted for inflation, that amounts to about $40.43 million today.

There are just three players who will earn that much in 2023: Max Scherzer and Justin Verlander ($43.3 million each) and Aaron Judge ($40 million). That makes the deal Judge signed this month the closest comp to what Trout agreed to play for nearly a decade ago.

But it’s interesting to note that the game’s top end annualized salaries have begun to lag inflation. Trout is now playing under terms of a $12 year, 426.5 million contract he signed in 2020. He will be paid $37.1 million to do so.

But when adjusted for inflation, that’s actually less than what he signed for nearly a decade ago. The $34.1 million he earned in 2018 adjusts to more than $40.4 million in current money.

Next. Ranking the 12 winningest teams in MLB history. dark

In his 2020 deal, Trout and his agent made the deliberate decision to accept less on an annualized basis in exchange for the security of a deal that will pay him $37.1 million through the remainder of this decade, so he’s probably going to be OK.